Shapers of Japanese History

Mishima Yukio: Historical Visionary

2 October 2020

Mishima Yukio’s literary creations, imbued with his individualistic aesthetic sense, have enthralled readers around the world. In the year that marks the fiftieth anniversary of his suicide, Mishima expert Inoue Takashi looks back on the writer’s life.

Fifty years ago, Mishima Yukio died dramatically, killing himself by seppuku after his calls to reform Japan’s postwar Constitution failed to inspire Self-Defense Forces to rise up at a base in Tokyo. The death of the renowned author, nominated five times for the Nobel prize in literature, caused shock in Japan and around the world, but his motives were hard to fathom. Half a century later the mysteries remain, and critics continue to investigate the meaning of his literature and suicide.

Mishima was born Hiraoka Kimitake in 1925. As the Shōwa era (1926–89) began the following year, the author’s age remained in step with the numbering of the era; he was 20 in 1945 (Shōwa 20) and 45 when he died in 1970 (Shōwa 45). Divide the period into three, and there are the first 20 years of Shōwa that were dominated by years of warfare culminating in unprecedented collapse, the next 25 of rapid economic growth that lifted the country up from its burnt-out ruins, and the 20 or so that followed. Mishima’s life overlapped with the first two of these parts, which could be seen as most representative of the period as a whole. Although the curtain finally came down on the Shōwa era in 1989, as the economic bubble burst, he could be said to have already followed its spirit to the grave.

Mishima believed that literary works represented their age, while at times expressing disagreement and offering new historical visions. This was particularly the case from his 1956 work Kinkakuji (trans. The Temple of the Golden Pavilion) onward. The main genre of modern Japanese literature was the I-novel, in which authors sincerely recorded their own experiences and incidents around them; writers with the same sense of creativity as Mishima were extremely rare. On the international stage, however, authors celebrated for their contributions to the novel like Balzac, Flaubert, Thomas Mann, Tolstoy, and Dostoyevsky all transcended their era, criticizing society and thrusting their artistic vision on the world. Mishima was a writer in this tradition.

Debut at 16

Mishima was born in Yotsuya, Tokyo. This was technically in the prestigious Yamanote district on the west side of the city center, but in fact it was a poor locality, left behind in the reconstruction that followed the Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923. His grandmother Natsuko, from a distinguished samurai family, was dissatisfied with the living environment there. Mishima’s grandfather was formerly the governor of the southern half of the island known as Karafuto in Japan (now wholly administered by Russia as Sakhalin). However, he was forced out of office after a bribery scandal, and Natsuko compensated for her lost dreams and shattered self-esteem through devotion to her grandson.

As Natsuko suffered from sciatica and Mishima had a weak constitution, they often spent their days together in the sickroom. Mishima, who loved fairy tales and picture books, later let his own imagination fly, drawing and writing stories. In “Sekai no kyōi” (The Wonder of the World), a story he wrote when he was 10, autumn comes to an island paradise and with the extinguishing of a candle, it is plunged into darkness.

Although Mishima was not himself from an aristocratic family, he attended Gakushūin, a school for children of the upper classes. His poor health played a part in his undistinguished performance in elementary school. From junior high school, however, his teachers helped lift him to become one of the institution’s outstanding students. At 16, he made his literary debut with his first story to be published outside school magazines. In “Hanazakari no mori” (The Forest in Full Flower; 1941), the narrator enters the flow of time before he was born, and rediscovers the origin of life. This was when Mishima adopted his pen name. It was also the year Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, initiating the Pacific War.

Mishima graduated from Gakushūin High School at the top of his class in 1944 and enrolled in the Faculty of Law at Tokyo Imperial University (now the University of Tokyo). Although poor health exempted him from military service, Mishima’s first collection that year, bringing together “The Forest in Full Flower” with four other stories, had been intended as a posthumous publication. The end of the war the following year left him facing a dilemma. Older authors forced into silence during the war years and up-and-coming writers back from the battlefields let forth a flood of fiction, while Mishima, who despite his youth had been creatively active during this time, found he had lost his place in the literary world. Half deciding to abandon his idea of becoming a novelist, he joined the Ministry of Finance after graduating from university, and began on the bureaucratic career path.

Instead of giving up fiction, however, Mishima quit his job at the ministry after nine months to work on a new novel. Kamen no kokuhaku (trans. Confessions of a Mask), published in 1949, had a narrator based on the author himself, who looks back on the circumstances that led him to accept his homosexuality. In one notable scene, the narrator first becomes sexually excited on seeing a picture of the martyrdom of Saint Sebastian, who was bound to a tree and shot with arrows. The novel did not represent Mishima’s own coming out as gay, though. Rather, with an insistence that everyone is wearing masks, it poured cold water on the kind of sensibility that believes unquestioningly in the identity of the self. This irony resounded with the psychologically troubled young people who had to live through the chaos of wartime and the immediate postwar period, making Confessions of a Mask a bestseller.

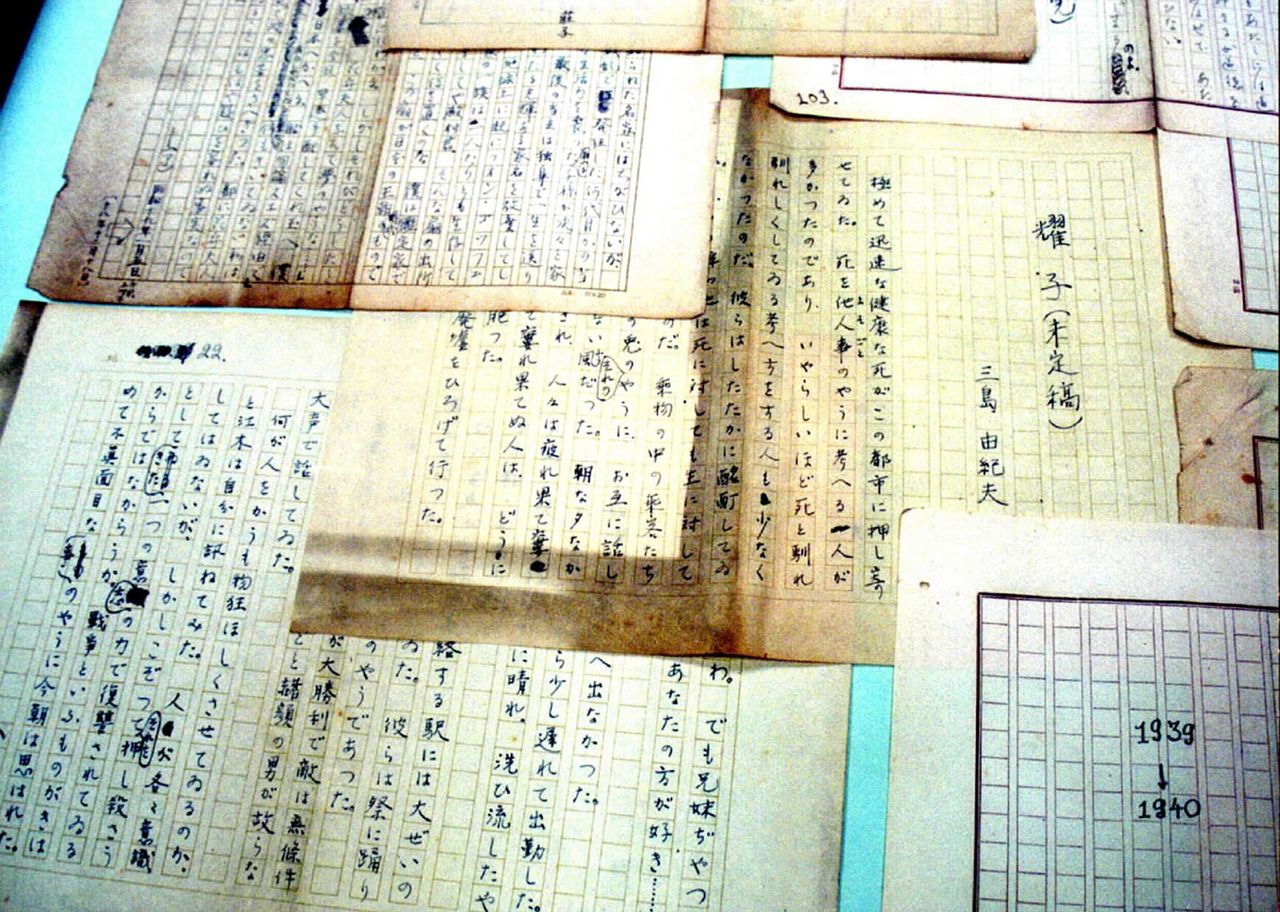

Unpublished manuscripts by Mishima Yukio. In 2000, 183 works of fiction and criticism written by Mishima in his late teens and early twenties were discovered. These are at the Mishima Yukio Literary Museum in Yamanakako, Yamanashi Prefecture. (© Jiji)

Success and Miscalculation

Having returned to the literary scene, Mishima drew a lively picture of the gay community in occupied Japan in Kinjiki (trans. Forbidden Colors), published from 1951 to 1953, and presented an innocent story of first love in his 1954 Shiosai (trans. The Sound of Waves). He also ventured into drama with the 1956 collection Kindai nōgakushū (trans. Five Modern Nō Plays) and the 1954 kabuki play Iwashiuri koi no hikiami (trans. The Sardine Seller’s Net of Love). In 1956, at the age of 31 he published The Temple of the Golden Pavilion, based on the real-life arson of Kinkakuji, the titular Kyoto temple, by one of its acolytes in 1950. It became one of his best received works and was translated into many languages.

By the time it was published, Japan’s economic boom years had begun. What drew so many readers to this novel about the arson incident of six years before? Reborn after the tribulations of war, the country was rising toward prosperity. Even so, it was only a decade or so since the war ended, and the dark memories of that time were slow to fade. They remained deeply rooted in people’s minds as an inner threat to the bright dreams of postwar democracy, progress, and affluence. The Temple of the Golden Pavilion spoke for the internal unease many in the new society felt.

From the inner perspective, democracy and economic growth were nothing other than masks. Continuing to wear them meant losing sight of the roots of existence, and falling into nihilism. Mishima made nihilism the subject of his 1959 work Kyōko no ie (Kyōko’s House), which tells the story of four young people leading lonely lives in Tokyo and New York around 1955.

(From left to right) Authors Mishima Yukio, Abe Kōbō, Ishikawa Jun, and Kawabata Yasunari come together to read a joint statement in Tokyo on February 28, 1967, protesting against the Cultural Revolution in China. (© Jiji)

Here he made a great miscalculation. The generation of readers who embraced The Temple of the Golden Pavilion were lukewarm about Kyōko’s House. By 1959, the people bustling through a new and bigger economic boom were no longer interested in the question of nihilism. For Mishima, who had tried to depict some of the darker aspects of the age in his novel, this was a grave shock.

The Final Manuscript

Mishima went on to seek new ways of being outside the literary sphere, acting in the 1960 gangster movie Karakkaze yarō (Afraid to Die) and becoming the subject of the 1963 photography collection Barakei (Ordeal by Roses) by Hosoe Eikō. With their success, he became a media favorite.

This meant, however, catering to the postwar society that made no attempt to understand Kyōko’s House. The greater the media reaction he stirred up, the greater his sense of self-denial. To counter this situation, he could only take on the challenge of creating a literary work that captured the age and offered a new vision of history on a greater scale than ever before. This was the tetralogy Hōjō no umi (trans. The Sea of Fertility).

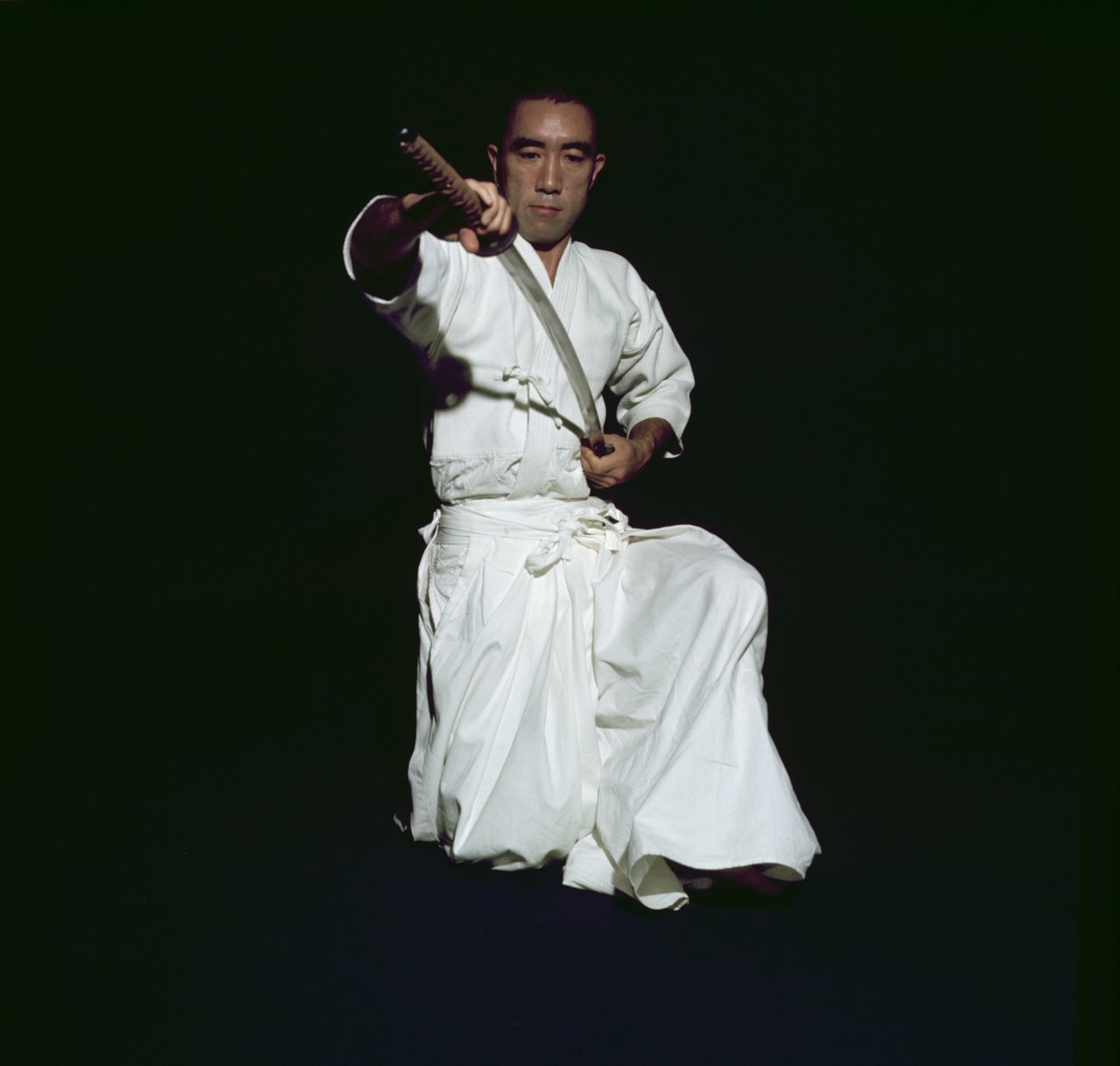

Mishima Yukio practicing the martial art of iaidō on July 3, 1970. (© Jiji)

In the four books, its protagonist apparently reincarnates through the twentieth century. The opening depicts a memorial ceremony for those who died in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–5. Its bleak atmosphere lingers in the background throughout The Sea of Fertility, demonstrating that the roots of postwar nihilism were already present in the Meiji era (1868–1912). As the successive reincarnations fight against this rejection of principles in their pursuit of life, a joyful enlightenment seems certain in the final part.

However, while this was the ending in the original concept, the fourth book actually finishes with the twist that the stories of reincarnation were no more than an illusion. After handing the final manuscript in to be edited on November 25, 1970, Mishima caused a sensation with his suicide. The truth behind the act is still unknown. One thing I can say is that Mishima vividly portrayed the nihilism the age was moving toward in his ending to The Sea of Fertility. I take his death by his own hand as having been an act aimed at encouraging each one of us to discover how to overcome that nihilism.

(Originally published in Japanese on August 26, 2020. Banner photo: Mishima Yukio in 1970. © Jiji.)

***

Inoue Takashi

Professor at Shirayuri University. Specializes in Mishima Yukio and other modern Japanese literature. Born in Yokohama in 1963. Graduated from Tokyo University, where he also conducted graduated work. Was a lecturer and associate professor at Shirayuri University before taking on his current position in 2008. Works include Mō hitotsu no Nihon o motomete: Mishima Yukio Hōjō no umi o yominaosu (Seeking Another Japan: A Reassessment of Mishima Yukio’s The Sea of Fertility) and Mishima Yukio Hōjo no umi vs. Noma Hiroshi Seinen no wa: Sengo bungaku to zentai shōsetsu (Mishima Yukio’s The Sea of Fertility vs. Noma Hiroshi’s Ring of Youth: Postwar Literature and the Total Novel).

NIPPON