IMDb-BEWERTUNG

5,5/10

2451

IHRE BEWERTUNG

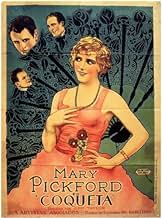

Füge eine Handlung in deiner Sprache hinzuA flirtatious Southern belle is compromised with one of her suitors.A flirtatious Southern belle is compromised with one of her suitors.A flirtatious Southern belle is compromised with one of her suitors.

- 1 Oscar gewonnen

- 3 wins total

Johnny Mack Brown

- Michael Jeffery

- (as John Mack Brown)

Jay Berger

- Little Boy on Street

- (Nicht genannt)

Phyllis Crane

- Bessie

- (Nicht genannt)

Joseph Depew

- Joe

- (Nicht genannt)

Robert Homans

- Court Bailiff

- (Nicht genannt)

Dorothy Irving

- Girl

- (Nicht genannt)

Vera Lewis

- Miss Jenkins

- (Nicht genannt)

Craig Reynolds

- Young Townsman at Dance

- (Nicht genannt)

Empfohlene Bewertungen

It's rather unfortunate that this is the only film for which many current movie fans remember Mary Pickford, because of the neglect of silent films and because of the undue weight given to well-known but arbitrary motion picture awards. While she is often unfairly blamed for the mediocre quality of "Coquette", the fault really lies elsewhere. Without a thorough adaptation of the material to make it more suitable for the screen, hardly anyone could have performed well enough to make this much better.

The story did hold possibilities, but it's the kind of familiar, rather routine melodrama that needs interesting characters, unusual situations, or snappy dialogue to make it work. There is none of that here - only a talky and generally predictable script, which would work better as a stage play or even a radio play. Neither Pickford nor Johnny Mack Brown has much of a chance to give it life. They do their best, and they simply perform their roles as they were written. Nor is it one of the worst movies ever - it does contain some stretches of genuinely good acting, and the story is at least a little better than the warmed-over scenarios of so many recent movies.

Pickford deserves to be remembered for her many fine performances during the silent era. She could also have made top quality talking films if she had been given the chance, but she was never given roles that allowed her to use her greatest strengths. Further, in the early sound era, producers and directors were overly interested in dialogue-heavy pictures like this, which seemed impressive at the time only because talking pictures were still a novelty. Audiences of the day enjoyed them, but now they look as dated and dull as today's over-praised computer-imagery extravaganzas will look in fifty years or so. None of that is the fault of the actors and actresses of the era.

The story did hold possibilities, but it's the kind of familiar, rather routine melodrama that needs interesting characters, unusual situations, or snappy dialogue to make it work. There is none of that here - only a talky and generally predictable script, which would work better as a stage play or even a radio play. Neither Pickford nor Johnny Mack Brown has much of a chance to give it life. They do their best, and they simply perform their roles as they were written. Nor is it one of the worst movies ever - it does contain some stretches of genuinely good acting, and the story is at least a little better than the warmed-over scenarios of so many recent movies.

Pickford deserves to be remembered for her many fine performances during the silent era. She could also have made top quality talking films if she had been given the chance, but she was never given roles that allowed her to use her greatest strengths. Further, in the early sound era, producers and directors were overly interested in dialogue-heavy pictures like this, which seemed impressive at the time only because talking pictures were still a novelty. Audiences of the day enjoyed them, but now they look as dated and dull as today's over-praised computer-imagery extravaganzas will look in fifty years or so. None of that is the fault of the actors and actresses of the era.

More than the silents that preceded it, this is a rare glimpse into a world that is almost impossible for our generation to imagine. The acting style seems bizarre by modern standards. The characters walk as if they were trying to dance, and they speak as if they would rather sing their lines. Okay, sound equipment may have been awful then - "talkies" were brand new in 1929 - but that fact does nothing to make it less pretentious when the characters stretch their mouths to yawn proportions to utter dated lines like, "darling, I love you more than life itself."

Then there's the plot, another feature of this film that is as quaint as the acting and the dialogue. "Norma," played legendary silent screen actress Mary Pickford at the end of her prolific career, becomes "compromised" by a night with a boyfriend, Michael. Michael vows to marry her but instead finds himself in an angry confrontation with Norma's father, the doctor.

Father takes a gun to avenge his violated daughter - who is played, remember, by a 37-year-old woman. And poor Norma, finding her lover on his deathbed, pours forth a mind-numbing, melodramatic declaration of her love that had to have been way over the top even in those days.

But the most amazing part is the end, where the doctor is on trial for murder. Norma takes the stand to accuse her lover of rape and thus save her father, which she does admirably and with all the flourishes and eye-batting appropriate for the era. Suddenly, the father's conscience is stirred and he rushes to the feet of his daughter - this in a court of law - and pleads with her to let him take the blame with honor. The doctor eyes the murder weapon, a revolver sitting on a table before the judge, and then stands before the court and demands that he pay his debt to the state. Imagine that!

Father then rushes to the arms of daughter and begs her to "hug daddy" as she used to. What follows was surely, even to audiences of the day, an excessively-long, gruesomely-sentimental embrace. To a modern viewer seeing it in the contemporary context, it would clearly suggest incest, though this was certainly not the meaning of the scene. That done, father grabs gun and commits suicide in the courtroom. To the film's credit, the event is conveyed well by the sound of a single gunshot - no blood.

Pickford may have been the darling of silent film, and she was undeniably a remarkable actress in that setting. But her talkie debut is flawed in every conceivable way, from the bogus southern accents of her and others' characters to the comical arm gestures she makes to emphasize her schmaltzy love-talk with Michael.

You have to cut this film some slack not only for the year it was made, but also because sound movies were then in their infancy. Still, the story line and script are painfully exaggerated and the acting horribly stilted.

But is it worth watching? I say yes. It's important cinema history. And it's fun.

Then there's the plot, another feature of this film that is as quaint as the acting and the dialogue. "Norma," played legendary silent screen actress Mary Pickford at the end of her prolific career, becomes "compromised" by a night with a boyfriend, Michael. Michael vows to marry her but instead finds himself in an angry confrontation with Norma's father, the doctor.

Father takes a gun to avenge his violated daughter - who is played, remember, by a 37-year-old woman. And poor Norma, finding her lover on his deathbed, pours forth a mind-numbing, melodramatic declaration of her love that had to have been way over the top even in those days.

But the most amazing part is the end, where the doctor is on trial for murder. Norma takes the stand to accuse her lover of rape and thus save her father, which she does admirably and with all the flourishes and eye-batting appropriate for the era. Suddenly, the father's conscience is stirred and he rushes to the feet of his daughter - this in a court of law - and pleads with her to let him take the blame with honor. The doctor eyes the murder weapon, a revolver sitting on a table before the judge, and then stands before the court and demands that he pay his debt to the state. Imagine that!

Father then rushes to the arms of daughter and begs her to "hug daddy" as she used to. What follows was surely, even to audiences of the day, an excessively-long, gruesomely-sentimental embrace. To a modern viewer seeing it in the contemporary context, it would clearly suggest incest, though this was certainly not the meaning of the scene. That done, father grabs gun and commits suicide in the courtroom. To the film's credit, the event is conveyed well by the sound of a single gunshot - no blood.

Pickford may have been the darling of silent film, and she was undeniably a remarkable actress in that setting. But her talkie debut is flawed in every conceivable way, from the bogus southern accents of her and others' characters to the comical arm gestures she makes to emphasize her schmaltzy love-talk with Michael.

You have to cut this film some slack not only for the year it was made, but also because sound movies were then in their infancy. Still, the story line and script are painfully exaggerated and the acting horribly stilted.

But is it worth watching? I say yes. It's important cinema history. And it's fun.

The earliest sound movies quickly became known as "talkies", as oppose to "soundies" as one might expect them to be called. It makes sense though, because these pictures tended to have a lot more talking in them than did the sound films of a few years later. The reason is most of them were culled from stage plays (where speech largely takes the place of action) because this was seen as the most appropriate material for the new technology. And back then, theatre was not the prestigious medium it is today. Just as there have been B-movies and dime novels, so too were there plenty of cheap and cheerful stage plays ripe for adaptation to the screen.

Coquette comes from a play by the rarely-remembered theatre legend George Abbott along with Ann Preston Bridgers, and is essentially a melodrama-by-numbers. All the familiar hackneyed elements are here – a flirtatious young woman, a disapproving father, a gun going off and so on. It is all a rather silly affair, putting some rather large strains on credibility in its final act. And in its translation to the screen it has retained the structure of a theatrical play. On the stage you can't cut back-and-forth from one place to another, so big chunks of plot will take place consecutively, often in the same room. And this looks odd in a movie.

Coquette is probably best remembered now as the movie for which (mostly) silent star Mary Pickford won her only Oscar for acting. The deservedness of this award has since been called into question. Her performance is an abundance of mannerisms, but while certainly overt it never quite goes over-the-top, which is a fair feat given the plot requires her to go through every conceivable emotional state. She is actually at her best when saying nothing, such as the odd little expression that crosses her face at the end of the court scene. The best turn however belongs to John St. Polis, who gives a nice solid performance. Theatrical, but solid. By contrast though, the unbearable woodenness of John Mack Brown is like an acting black hole, threatening to drag what little credibility the movie has left into oblivion, and would have succeeded if someone hadn't had the good sense to pop a cap in his ass halfway through. Ironically Brown was to have the most lucrative post-Coquette career of all the cast, albeit largely in B-Westerns.

The director may seem like a strange choice. Sam Taylor was first a gag man and then a director at Hal Roach's comedy studios, but lately he had got into drama. Staging in depth was always one of his fortes, and he makes some neat little compositions which really give definition to the limited number of sets. For example when Brown first comes on the scene, he has him in the background with Pickford on screen right and Matt Moore a little closer to the screen on the left, creating a zigzag pattern. He also makes some attempt to bring a bit of cinematic dynamism to what is essentially a filmed play, making sharp changes of angle at key moments such as St. Polis's walking in on Pickford and Brown, but by-and-large the fact that nearly everything takes place in one room – or rather a frontless set – is inescapable.

Perhaps we shouldn't be too hard on Coquette, as its flaws are really only the flaws of its era. And in all honesty, if you try not to take it too seriously it can be enjoyed on a certain level, especially since it runs for a mere 75 minutes. But then again, there were also plenty of pictures from this early talkie era – yes, even as early as 1929 – that managed to rise above their circumstances. And after a look at how much talent and imagination there really was in Hollywood at the time, it's not difficult to see how Coquette could have been so much more.

Coquette comes from a play by the rarely-remembered theatre legend George Abbott along with Ann Preston Bridgers, and is essentially a melodrama-by-numbers. All the familiar hackneyed elements are here – a flirtatious young woman, a disapproving father, a gun going off and so on. It is all a rather silly affair, putting some rather large strains on credibility in its final act. And in its translation to the screen it has retained the structure of a theatrical play. On the stage you can't cut back-and-forth from one place to another, so big chunks of plot will take place consecutively, often in the same room. And this looks odd in a movie.

Coquette is probably best remembered now as the movie for which (mostly) silent star Mary Pickford won her only Oscar for acting. The deservedness of this award has since been called into question. Her performance is an abundance of mannerisms, but while certainly overt it never quite goes over-the-top, which is a fair feat given the plot requires her to go through every conceivable emotional state. She is actually at her best when saying nothing, such as the odd little expression that crosses her face at the end of the court scene. The best turn however belongs to John St. Polis, who gives a nice solid performance. Theatrical, but solid. By contrast though, the unbearable woodenness of John Mack Brown is like an acting black hole, threatening to drag what little credibility the movie has left into oblivion, and would have succeeded if someone hadn't had the good sense to pop a cap in his ass halfway through. Ironically Brown was to have the most lucrative post-Coquette career of all the cast, albeit largely in B-Westerns.

The director may seem like a strange choice. Sam Taylor was first a gag man and then a director at Hal Roach's comedy studios, but lately he had got into drama. Staging in depth was always one of his fortes, and he makes some neat little compositions which really give definition to the limited number of sets. For example when Brown first comes on the scene, he has him in the background with Pickford on screen right and Matt Moore a little closer to the screen on the left, creating a zigzag pattern. He also makes some attempt to bring a bit of cinematic dynamism to what is essentially a filmed play, making sharp changes of angle at key moments such as St. Polis's walking in on Pickford and Brown, but by-and-large the fact that nearly everything takes place in one room – or rather a frontless set – is inescapable.

Perhaps we shouldn't be too hard on Coquette, as its flaws are really only the flaws of its era. And in all honesty, if you try not to take it too seriously it can be enjoyed on a certain level, especially since it runs for a mere 75 minutes. But then again, there were also plenty of pictures from this early talkie era – yes, even as early as 1929 – that managed to rise above their circumstances. And after a look at how much talent and imagination there really was in Hollywood at the time, it's not difficult to see how Coquette could have been so much more.

Mary Pickford won the Best Actress Oscar for her performance in this film - and this fact has dominated the way people have treated it over the years. Yes, perhaps her award had more to do with her power than her performance - but the performance is actually pretty good. At times she rises to great emotional heights - the death scene is quite extraordinary and the court-room sequence powerful. Of course she's too old for the role - but she was too old for nearly every part she ever played, and just a few years later Leslie Howard and Norma Shearer played Romeo and Juliet to great acclaim - so such age issues were probably not issues in 1929.

It is true that she talks a little like an adult Shirley Temple (did Shirley model herself on Mary - they certainly played many of the same roles?)- but her silent acting is excellent - her looks can really kill.

The supporting cast is not very good, except for the wonderful Louise Beavers, - but Johnny Mack Brown is devastatingly handsome as Mary's love interest. The script betrays its stage origins, and the film suffers the same problems most early talkies suffer - inadequate use of music, poorly synchronised sound effects, completely absent sound effects (eg doors opening and closing silently), and limited movement of both actors and camera.

But all things considered this is a worthwhile little film - certainly not great but not as bad as myth would have it. And the ending is really gorgeous. Watching the great silent stars struggling in early talkies, I always feel that they were learning a new craft, just as the cameramen, directors and writers were. Sadly the audiences were less forgiving of their beloved stars than they were of those unseen behind the camera, and rejected them before they had a chance to develop a new acting technique. I can't help thinking that, if they had been given the chance, many of these actors would have been great talkie actors. The technicians were allowed to develop but, by the time they were skilled enough to make the actors look and sound good, most of the old stars had gone. The supreme example of a silent star who was allowed to develop is, of course, Garbo - and, to a lesser extent, Ramon Novarro (but he could sing - which helped). Is it possible that, given the same opportunities as Garbo, we may have seen Fairbanks, Pickford, Talmadge, Swanson, Bow, Brooks, Gish, Gilbert, Colleen Moore, Leatrice Joy etc for many more years than we were allowed? But within ten years of this film being made Gilbert and Fairbanks were dead, Gish was carving out a new career on the stage, Pickford, Swanson, Bow, Talmadge, Brooks and Moore had retired, Joy was doing the occasional character role and even Ramon Novarro was out of work. What a waste!

It is true that she talks a little like an adult Shirley Temple (did Shirley model herself on Mary - they certainly played many of the same roles?)- but her silent acting is excellent - her looks can really kill.

The supporting cast is not very good, except for the wonderful Louise Beavers, - but Johnny Mack Brown is devastatingly handsome as Mary's love interest. The script betrays its stage origins, and the film suffers the same problems most early talkies suffer - inadequate use of music, poorly synchronised sound effects, completely absent sound effects (eg doors opening and closing silently), and limited movement of both actors and camera.

But all things considered this is a worthwhile little film - certainly not great but not as bad as myth would have it. And the ending is really gorgeous. Watching the great silent stars struggling in early talkies, I always feel that they were learning a new craft, just as the cameramen, directors and writers were. Sadly the audiences were less forgiving of their beloved stars than they were of those unseen behind the camera, and rejected them before they had a chance to develop a new acting technique. I can't help thinking that, if they had been given the chance, many of these actors would have been great talkie actors. The technicians were allowed to develop but, by the time they were skilled enough to make the actors look and sound good, most of the old stars had gone. The supreme example of a silent star who was allowed to develop is, of course, Garbo - and, to a lesser extent, Ramon Novarro (but he could sing - which helped). Is it possible that, given the same opportunities as Garbo, we may have seen Fairbanks, Pickford, Talmadge, Swanson, Bow, Brooks, Gish, Gilbert, Colleen Moore, Leatrice Joy etc for many more years than we were allowed? But within ten years of this film being made Gilbert and Fairbanks were dead, Gish was carving out a new career on the stage, Pickford, Swanson, Bow, Talmadge, Brooks and Moore had retired, Joy was doing the occasional character role and even Ramon Novarro was out of work. What a waste!

The chief flaw of Coquette is the generally poor quality of the sound which sometimes fades entirely, making it difficult to follow the plot which is propelled mostly by spoken exposition as opposed to purely cinematic techniques. The play on which it is based was a hit for Helen Hayes on Broadway but was sanitized and oversimplified for the screen (not at all unusual in those days). Dialogue and acting are florid and broad but nevertheless the story does manage to hold the attention. A doctor's daughter (Mary Pickford) outrages her tradition- bound father (John St. Polis) by falling in love with an uncultivated fellow from "the hills" (John Mack Brown). A fatal shooting results, but I won't give away the exact circumstances here.

Although she was in her mid-30's at the time of filming, Pickford is convincing, if somewhat mannered, as the maiden with one foot still in girlhood, displaying wide emotional range and a masterful command of her body, no surprise considering the physicality of her long silent film career. Her diminutive stature also works in her favor. When she sits in the maid's lap for consolation she really does look like the little girl she had played for so many years. Sadly, she is made to spend a great deal of time sobbing hysterically. (Vivien Leigh had to deal with the same requirement in Gone with the Wind ten years later.) Although not much of an actor, John Mack Brown has a kind of animal appeal, with a relatively deep, strong voice which registers clearly; one can understand why he became a popular player in talking films. Here, he seems to seesaw between menace and tenderness and you just have to give him the benefit of the doubt. Otherwise you cannot believe Pickford's feelings towards him. St. Polis has a stately presence and a sonorous, trained voice and seems the most comfortable of the supporting players in his role. The character of the black maid played by Louise Beavers departs from the norm; she moves torpidly and even talks back to the master's teenage son when he tries to rush her through her chores.

There is a lively scene at a country club featuring a jazz band and young revelers stomping to the hotsy-totsy musical numbers with wild abandon, suggesting that the later jitterbug and sixties dances did not come out of nowhere. The courtroom climax is hard to swallow did judges in the South or anywhere else ever allow witnesses to sit in the laps of defendants for long personal dialogues while on the stand?

Although she was in her mid-30's at the time of filming, Pickford is convincing, if somewhat mannered, as the maiden with one foot still in girlhood, displaying wide emotional range and a masterful command of her body, no surprise considering the physicality of her long silent film career. Her diminutive stature also works in her favor. When she sits in the maid's lap for consolation she really does look like the little girl she had played for so many years. Sadly, she is made to spend a great deal of time sobbing hysterically. (Vivien Leigh had to deal with the same requirement in Gone with the Wind ten years later.) Although not much of an actor, John Mack Brown has a kind of animal appeal, with a relatively deep, strong voice which registers clearly; one can understand why he became a popular player in talking films. Here, he seems to seesaw between menace and tenderness and you just have to give him the benefit of the doubt. Otherwise you cannot believe Pickford's feelings towards him. St. Polis has a stately presence and a sonorous, trained voice and seems the most comfortable of the supporting players in his role. The character of the black maid played by Louise Beavers departs from the norm; she moves torpidly and even talks back to the master's teenage son when he tries to rush her through her chores.

There is a lively scene at a country club featuring a jazz band and young revelers stomping to the hotsy-totsy musical numbers with wild abandon, suggesting that the later jitterbug and sixties dances did not come out of nowhere. The courtroom climax is hard to swallow did judges in the South or anywhere else ever allow witnesses to sit in the laps of defendants for long personal dialogues while on the stand?

Wusstest du schon

- WissenswertesMary Pickford was initially horrified to hear her recorded voice for the first time in this film: "That's not me. That's a pipsqueak voice. It's impossible! I sound like I'm 12 or 13!"

- Zitate

Jasper Carter: Did Michael Jeffery make love to you there?

Norma Besant: Yes.

Jasper Carter: Did you resist him?

Norma Besant: Yes.

Jasper Carter: But he forced his attention?

Norma Besant: Yes.

Jasper Carter: And you could not resist his lovemaking?

Norma Besant: No.

Jasper Carter: And he made you yield?

Norma Besant: Yes.

Jasper Carter: He made you yield to an extreme?

Norma Besant: Yes.

- VerbindungenEdited into American Experience: Mary Pickford (2005)

Top-Auswahl

Melde dich zum Bewerten an und greife auf die Watchlist für personalisierte Empfehlungen zu.

- How long is Coquette?Powered by Alexa

Details

- Erscheinungsdatum

- Herkunftsland

- Sprache

- Auch bekannt als

- Coquette: A Drama of the American South

- Drehorte

- Produktionsfirma

- Weitere beteiligte Unternehmen bei IMDbPro anzeigen

Box Office

- Budget

- 489.106 $ (geschätzt)

- Laufzeit

- 1 Std. 16 Min.(76 min)

- Farbe

- Seitenverhältnis

- 1.20 : 1

Zu dieser Seite beitragen

Bearbeitung vorschlagen oder fehlenden Inhalt hinzufügen