Füge eine Handlung in deiner Sprache hinzuA love triangle develops in a traveling minstrel troupe.A love triangle develops in a traveling minstrel troupe.A love triangle develops in a traveling minstrel troupe.

- Auszeichnungen

- 1 wins total

Allan Cavan

- Doctor

- (Nicht genannt)

Richard Cramer

- Detective

- (Nicht genannt)

Stanley Fields

- Pig Eyes

- (Nicht genannt)

Lloyd Ingraham

- Deputy Sheriff

- (Nicht genannt)

Ben Taggart

- Sheriff

- (Nicht genannt)

Grant Withers

- Reporter in Trailer

- (Nicht genannt)

Empfohlene Bewertungen

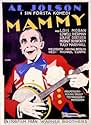

Mammy (1930)

** (out of 4)

Al Fuller (Al Jolson) is an entertainer in a minstrel show who just happens to be in love with a woman (Lois Moran) who can't have him because she's in love with another performer (Lowell Sherman). During the act there's a sequence where Fuller must shoot the "other man" but after doing so this night a real bullet comes out. Fuller runs off to his mother who tells him he should go back and face the music. Fans of Al Jolson swear up and down that the entertainer doesn't get the credit he deserves today because of the fact that he appeared in blackface. The actor will always be remembered by film buffs for THE JAZZ SINGER but I'm going to go against some of the fans and say that he's not better remembered today not due to the blackface but because of the fact that his movies simply aren't that good. MAMMY is the perfect example of this. The performances are bad. The story is downright silly. The talking sequences are all rather lame but this can be blamed on the technology of the time. Curtiz, one of the greatest directors from the Golden Age of Hollywood, is absent throughout much of the running time. We can start with the story as it's just downright silly and it's easy to say that not much time was spent on it as the studio was clearly more worried about the music. That's understandable so we can let the bad story slide. Curtiz' direction really doesn't bring any of the material to life and just check out how poorly shot the opening sequence is in the rain. The other minstrel show stuff will probably offend most people but I've seen enough movies and know enough about history to realize that this type of thing was accepted in 1930. Still, seeing a bunch of actors in blackface singing "Yes! We Have No Bananas" is probably going to be too much. The music numbers are the only thing that makes this worth viewing as there's no question that Jolson has a terrific voice and it can be heard in some great songs including "Yes, Sir, That's My Baby," "Mammy," "In the Morning," and several others. Jolson does his best to keep the energy going but he's given some pretty poor dialogue including some really lame jokes. The supporting players don't help too much either but then again the screenplay isn't doing them any favors. MAMMY is probably best known for the two sequences shot in 2-strip Technicolor. The picture quality today is quite rough but at the same time I was rather shocked at how incredibly bad the blackface looked in color. It looks like they would have done some more tests because just take a look at it during the first color number.

** (out of 4)

Al Fuller (Al Jolson) is an entertainer in a minstrel show who just happens to be in love with a woman (Lois Moran) who can't have him because she's in love with another performer (Lowell Sherman). During the act there's a sequence where Fuller must shoot the "other man" but after doing so this night a real bullet comes out. Fuller runs off to his mother who tells him he should go back and face the music. Fans of Al Jolson swear up and down that the entertainer doesn't get the credit he deserves today because of the fact that he appeared in blackface. The actor will always be remembered by film buffs for THE JAZZ SINGER but I'm going to go against some of the fans and say that he's not better remembered today not due to the blackface but because of the fact that his movies simply aren't that good. MAMMY is the perfect example of this. The performances are bad. The story is downright silly. The talking sequences are all rather lame but this can be blamed on the technology of the time. Curtiz, one of the greatest directors from the Golden Age of Hollywood, is absent throughout much of the running time. We can start with the story as it's just downright silly and it's easy to say that not much time was spent on it as the studio was clearly more worried about the music. That's understandable so we can let the bad story slide. Curtiz' direction really doesn't bring any of the material to life and just check out how poorly shot the opening sequence is in the rain. The other minstrel show stuff will probably offend most people but I've seen enough movies and know enough about history to realize that this type of thing was accepted in 1930. Still, seeing a bunch of actors in blackface singing "Yes! We Have No Bananas" is probably going to be too much. The music numbers are the only thing that makes this worth viewing as there's no question that Jolson has a terrific voice and it can be heard in some great songs including "Yes, Sir, That's My Baby," "Mammy," "In the Morning," and several others. Jolson does his best to keep the energy going but he's given some pretty poor dialogue including some really lame jokes. The supporting players don't help too much either but then again the screenplay isn't doing them any favors. MAMMY is probably best known for the two sequences shot in 2-strip Technicolor. The picture quality today is quite rough but at the same time I was rather shocked at how incredibly bad the blackface looked in color. It looks like they would have done some more tests because just take a look at it during the first color number.

In general, second rate material all around, though one of the minstrel numbers (the Yes We Have No Bananas Operatic Finale) is quite good. The plot is mainly an excuse to let Al Jolson do his stuff, but he can't carry it alone

The first part of the movie does give some idea what a white minstrel show might look like, including a parade in the rain.

I saw the UCLA restoration, which does include what is known to survive of the 2 color (red/green) Technicolor sequences. Unfortunately, sections of those sequences were lost when Dutch titles were inserted, and some of the cuts from color to sepia tinted black and white are not smooth.

The first part of the movie does give some idea what a white minstrel show might look like, including a parade in the rain.

I saw the UCLA restoration, which does include what is known to survive of the 2 color (red/green) Technicolor sequences. Unfortunately, sections of those sequences were lost when Dutch titles were inserted, and some of the cuts from color to sepia tinted black and white are not smooth.

Al Jolson occupies an unusual place in cinematic heritage. Dubbed the world's greatest entertainer, and certainly the most popular one in his day, Jolson will also forever remain famous for being the star of the world's first talking picture. And yet, due to much of his act and many of his screen appearances being in blackface, as well as the general quaintness of his style which owes far more to the musical hall than it does the screen, he is a figure whose work is today discussed far more than it is enjoyed.

Mammy was Jolson's fourth movie, and perhaps surprisingly is the first in which he had been paired with a major hit songwriter – in this case, Irving Berlin. The lesser-known Ray Henderson may have given Jolson his biggest hit with "Sonny Boy", but Irving's knack of mixing upbeat jollity with a bittersweet tug chimes in perfectly with Jolson's own style. The key song of Mammy is "Let Me Sing and I'm Happy" which is among Berlin's simplest both in melody and sentiment, and really suits Jolson's persona down to the ground.

Mammy also sees Jolson placed before a rather heavyweight director of dramas, namely Hungarian émigré Michael Curtiz, as opposed to comedy and musical specialist Lloyd Bacon who had helmed his previous two releases. Curtiz's tendency to fill up spaces with layers of extras and assorted business, tightly framing actors amid their settings isn't really what this picture needs, but nevertheless the director adds a few little touches to help ease out the story's emotions. Most notably we have several facial close-ups, a couple of Louise Dresser and one of Lois Moran. A pretty standard trick, but these are not just any close-ups. Take the one of Dresser after she has said goodbye to Jolson. Behind her we see some people walking to screen left, after which we cut to the train pulling away screen right, making it visually appear that the two shots are moving in opposite directions. Curtiz was also known to encourage restrained performances from his cast, and indeed we do get some beautifully understated turns from silent stars Louise Dresser and Hobart Bosworth. Even Al himself is a good deal more subtle under the influence of Curtiz.

However, the real key to Mammy's appeal – the reason why these pictures were more than just Jolson showcases – is the way that the songs are placed within the narrative. This is of course long before the days when the "integrated" musical was commonplace, and yet the emotional weight of each song has undergone consideration, probably by original "idea" writer Berlin, such story-based song deployment being another of his talents. Jolson's performance of "Looking at You" ironically comes just after his inadvertently putting himself in an embarrassing situation with Lois Moran, and the utter inappropriateness of the song at that moment increases that feeling of awkwardness. "Let Me Sing and I'm Happy" as well as being Jolson's introductory number, is reprised twice, firstly when he is about to be arrested, and again at the end of the picture – each time for completely different impact due to its placement. And this is something Jolson himself is clearly aware of, putting a veneer of professionalism over each rendition, but allowing his character's emotional state to show through according to the context in which the song is sung.

This may be one of the finest Jolson features, but ironically it was part of a downward turn in his career. His pictures were becoming repetitive, and now a few years into the talkie era he was less of a novelty. He would disappear from screens for a few years before reinventing himself as a more conventional musical star for the mid-30s, more or less divorced from his music-hall roots. Still, Mammy provides an opportunity to see him as he was to early audiences, before he even stepped in front of a camera, taking simple, hackneyed routines, pouring in his heart and soul and making them his own.

Mammy was Jolson's fourth movie, and perhaps surprisingly is the first in which he had been paired with a major hit songwriter – in this case, Irving Berlin. The lesser-known Ray Henderson may have given Jolson his biggest hit with "Sonny Boy", but Irving's knack of mixing upbeat jollity with a bittersweet tug chimes in perfectly with Jolson's own style. The key song of Mammy is "Let Me Sing and I'm Happy" which is among Berlin's simplest both in melody and sentiment, and really suits Jolson's persona down to the ground.

Mammy also sees Jolson placed before a rather heavyweight director of dramas, namely Hungarian émigré Michael Curtiz, as opposed to comedy and musical specialist Lloyd Bacon who had helmed his previous two releases. Curtiz's tendency to fill up spaces with layers of extras and assorted business, tightly framing actors amid their settings isn't really what this picture needs, but nevertheless the director adds a few little touches to help ease out the story's emotions. Most notably we have several facial close-ups, a couple of Louise Dresser and one of Lois Moran. A pretty standard trick, but these are not just any close-ups. Take the one of Dresser after she has said goodbye to Jolson. Behind her we see some people walking to screen left, after which we cut to the train pulling away screen right, making it visually appear that the two shots are moving in opposite directions. Curtiz was also known to encourage restrained performances from his cast, and indeed we do get some beautifully understated turns from silent stars Louise Dresser and Hobart Bosworth. Even Al himself is a good deal more subtle under the influence of Curtiz.

However, the real key to Mammy's appeal – the reason why these pictures were more than just Jolson showcases – is the way that the songs are placed within the narrative. This is of course long before the days when the "integrated" musical was commonplace, and yet the emotional weight of each song has undergone consideration, probably by original "idea" writer Berlin, such story-based song deployment being another of his talents. Jolson's performance of "Looking at You" ironically comes just after his inadvertently putting himself in an embarrassing situation with Lois Moran, and the utter inappropriateness of the song at that moment increases that feeling of awkwardness. "Let Me Sing and I'm Happy" as well as being Jolson's introductory number, is reprised twice, firstly when he is about to be arrested, and again at the end of the picture – each time for completely different impact due to its placement. And this is something Jolson himself is clearly aware of, putting a veneer of professionalism over each rendition, but allowing his character's emotional state to show through according to the context in which the song is sung.

This may be one of the finest Jolson features, but ironically it was part of a downward turn in his career. His pictures were becoming repetitive, and now a few years into the talkie era he was less of a novelty. He would disappear from screens for a few years before reinventing himself as a more conventional musical star for the mid-30s, more or less divorced from his music-hall roots. Still, Mammy provides an opportunity to see him as he was to early audiences, before he even stepped in front of a camera, taking simple, hackneyed routines, pouring in his heart and soul and making them his own.

7tavm

Just watched this on Warner Archive DVD. It also had the trailer for it in which star Al Jolson is "interviewed" by a reporter about his latest picture. I put "interviewed" in quotes because I'm sure that "reporter" was another actor helping plug the picture. Anyway, I enjoyed the story and performances though it's really Jolson's songs-mostly written by Irving Berlin-that help sell the movie on its merits. This version has the restored 2-strip Technicolor sequences that looked pretty good for its age. Some of those scenes had to be accompanied by sepia-toned black and white ones to show them complete which didn't distract me too much. In summary, Mammy-despite some now-politically incorrect stereotypes concerning the blackface sequences-was pretty entertaining.

If Mammy is remembered for anything it is for providing Al Jolson with one of his biggest song hits, definitely the biggest song hit he had written especially for the screen. Irving Berlin wrote this number for Jolson and he does it three times in his usual bravura style and on two of those occasions without black-face.

Al Jolson got his start in minstrel shows which were still popular at the turn of the 20th century. He's Al Fuller in this show, lead singer in this troupe and a man with a case of unrequited love for the owner of the show. From there springs the plot.

It's unfortunate for Jolson's current reputation that he did not abandon the black-face which was a carryover from his minstrel days. It's considered offensive now and rightly so. But listen to him sing Let Me Sing and I'm Happy and the rest of the score and you're hearing one of the great song stylists ever.

Irving Berlin wrote some original material for this film which was interpolated with some other standards. It is also good to hear Jolson do two of his comedy numbers, Who Paid the Rent for Mrs. Rip Van Winkle and Why Do They All Take the Night Boat to Albany. It's his ballads that he's remembered for today, but these numbers give you an idea of more of the kind of material he did on stage.

A lot of people will be rightly offended in seeing Mammy now, but like Bing Crosby's Dixie, it's an interesting piece of cinema history.

Al Jolson got his start in minstrel shows which were still popular at the turn of the 20th century. He's Al Fuller in this show, lead singer in this troupe and a man with a case of unrequited love for the owner of the show. From there springs the plot.

It's unfortunate for Jolson's current reputation that he did not abandon the black-face which was a carryover from his minstrel days. It's considered offensive now and rightly so. But listen to him sing Let Me Sing and I'm Happy and the rest of the score and you're hearing one of the great song stylists ever.

Irving Berlin wrote some original material for this film which was interpolated with some other standards. It is also good to hear Jolson do two of his comedy numbers, Who Paid the Rent for Mrs. Rip Van Winkle and Why Do They All Take the Night Boat to Albany. It's his ballads that he's remembered for today, but these numbers give you an idea of more of the kind of material he did on stage.

A lot of people will be rightly offended in seeing Mammy now, but like Bing Crosby's Dixie, it's an interesting piece of cinema history.

Wusstest du schon

- WissenswertesA preserved print of this film survives in the UCLA Film and Television archives.

- VerbindungenFeatured in Hollywood and the Stars: The Immortal Jolson (1963)

Top-Auswahl

Melde dich zum Bewerten an und greife auf die Watchlist für personalisierte Empfehlungen zu.

Details

- Laufzeit

- 1 Std. 24 Min.(84 min)

- Farbe

Zu dieser Seite beitragen

Bearbeitung vorschlagen oder fehlenden Inhalt hinzufügen