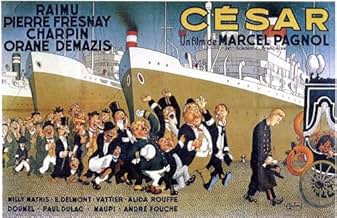

This final film of the Pagnol trilogy, written and produced by Pagnol, was also directed by Pagnol himself. Although all three films were very well directed indeed, this third one was the best directed of all. It contains many more exterior shots than the others and has 'extra doses of passion' because Pagnol was so emotionally involved in the story. Eighteen years have gone by since the end of the story told in FANNY (1932, see my review, and also my review of Part One, MARIUS, 1931). During all of that time, Marius has been away from Marseilles. He served for some years in the navy, and then he opened his own garage in the town of Toulon, where he is now living. Toulon is another port town on the Mediterranean, not far east of Marseilles. Toulon also happens to be the home town of the actor Raimu. Pagnol himself, by the way, was born at Aubagne, which is inland between Marseilles and Toulon. As this film opens, Panisse, the husband of Fanny and pretended father of the young lad Césariot, is seriously ill and lying in bed, possibly near to death. His friends, including César (played by the brilliant Raimu), think a priest should be fetched to hear Panisse's confession and to administer the last rites (known as Extreme Unction in the Catholic Church, which involves anointing the forehead with oil and committing the soul of the dying person to God's mercy). So a priest comes, but the entire section of the film concerning this episode is both raucous and hilarious, as the quayside friends behave in their usual irreverent and comical manner. As has been the case throughout all three of these films, wonderful comedy is continuously interwoven with all the tragic stories. Panisse insists on his final confession taking place in front of his friends, rather than in private with the priest, and this leads to some delightfully funny dialogue and scenes, especially when Panisse confesses that he has been naughty with some girls and his friends all tease him and joke about it while the priest tries to quieten them so that he can get on with his sombre task of preparing Panisse for death. The priest himself is teased, and the entire business can only be described as 'high comedy'. Then the priest kicks the friends out of the bedroom to have a private word with Panisse. He says that it is not acceptable that everyone knows that Césariot is really Marius's son, and not Panisse's, except for the boy himself. He says the boy must be told. Panisse does not want to do this. Eventually, however, the boy is told the truth by his mother, and he reacts very badly. He seeks out Marius at Toulon without identifying himself, and they get to know each other. Panisse dies but Marius does not want to return to face everyone in Marseilles whom he has not seen for 18 years. In the end, he does come back, and he and Fanny see each other again. But getting back together is not at all easy. Will they or won't they finally be reunited so that their great love can fully realized at last? Can several serious misunderstandings be cleared up? How will the son react if they do get back together? Can he get over his contempt for Marius and his shock at his mother having had him illegitimately? Meanwhile, the main focus of this film is upon César, whose only child, Marius, has at last returned to Marseilles after all those years of his father's desperate loneliness. How is he coping? Will Marius ever forgive him for insisting that he leave Fanny and his child with Panisse all those years ago? Will César ever forgive Marius for refusing to see him for 18 years and thus deserting his old father? Can anyone forgive anyone? As the characters work their ways through the tangles and knots of emotion and fate, the intensity of the story increases. All three of these films are peppered with marvellous supporting performances by utterly charming, maddening, impossible, and delightful local characters. Alida Rouffe is especially wonderful as Fanny's mother Honorine. Her very first film role, at the age of 57, was in MARIUS. She then not only appeared in the rest of the trilogy, but also in Pagnol's CIGALON (1935), Pagnol's TOPAZE (1936), and Pagnol's THE BAKER'S WIFE (1938, once again with Raimu). In 1939 she stopped working as an actress and only resumed again in 1946 (hence she refused to work under Vichy), for her very last film, dying in 1949 at the age of 79. She was one of the best French character actresses of her time, and Pagnol used her in six films, well appreciating her talents, which he himself had introduced to the screen in the first place. This trilogy by Pagnol may have plots which are as simple as daily life itself, but the three films rise to magnificence through the passionate belief in them of Pagnol, his troupe of actors, his co-directors, and apparently everyone associated with them, not to mention the people of Marseilles who found themselves being portrayed sympathetically in a medium which was usually dominated by the sophisticates of Paris. These films are classics in the grand sense. They will be watched and loved as long as there are people to see them. The world of the Old Port of Marseilles in the 1930s is long gone, but it lives on forever in this priceless record of its bygone time, subculture, and milieu which mixed sadness and hilarity in perfect harmony. Above all, these films are a lesson in authenticity, for they come alive with such childlike spontaneity, humour and tears, that they raise cinema to a true art form free of all artifice and made with such passion and love as has rarely been seen in the history of film.