Intolérance

Titre original : Intolerance: Love's Struggle Throughout the Ages

- 1916

- Tous publics

- 2h 43min

NOTE IMDb

7,7/10

18 k

MA NOTE

L'histoire d'une jeune femme pauvre, séparée de son mari et de son bébé à cause de préjugés, se mêle à d'autres récits d'intolérance issus d'autres époques.L'histoire d'une jeune femme pauvre, séparée de son mari et de son bébé à cause de préjugés, se mêle à d'autres récits d'intolérance issus d'autres époques.L'histoire d'une jeune femme pauvre, séparée de son mari et de son bébé à cause de préjugés, se mêle à d'autres récits d'intolérance issus d'autres époques.

- Réalisation

- Scénario

- Casting principal

- Récompenses

- 2 victoires au total

F.A. Turner

- The Dear One's Father

- (as Fred Turner)

Julia Mackley

- Uplifter

- (as Mrs. Arthur Mackley)

John P. McCarthy

- Prison Guard

- (as J.P. McCarthy)

Avis à la une

This silent film by director D.W. Griffith is well known to serious movie buffs and historians, but not to today's general public. I doubt that a lot of people these days would have the patience to sit through a film that contained three hours of silence. Nevertheless, the film's technical innovations inspired filmmakers in the 1920's and later, particularly in Russia and Japan. It also inspired filmmakers in the U.S., including Cecil B. DeMille and King Vidor. For this reason, and for other reasons, "Intolerance" is an important film.

The film's four interwoven stories, set in four different historical eras, are tied together thematically by the subject of "intolerance", a word which could be accurately interpreted today as "oppression", "injustice", "hate", "violence", and mankind's general inhumanity.

Griffith's narrative structure, though innovative, is uneven, because he gives more screen time to two of the four stories (the "modern" and the "Babylonian"). Equal time for three stories, thus deleting the fourth, might have worked better.

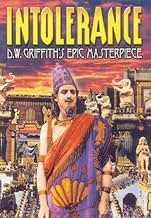

To me, the Babylonian story is the most interesting one because of its more complete coverage, and because of its elaborate costumes and spectacular sets. Even though there is no script, the viewer can easily discern the plot, which suggests that some of today's films might be just as effective, or more so, if screenwriters would downsize the dialogue.

What "Intolerance" offers most of all to contemporary viewers is a sense of perspective. Someone once said that despite the enormous advances in technology, society itself has advanced not at all. That may be true. In the eighty plus years since the film was released, technical advances in film-making have been obvious and impressive. But we are still plagued with the same old human demons of oppression, injustice, hate, violence, and ... intolerance.

The film's four interwoven stories, set in four different historical eras, are tied together thematically by the subject of "intolerance", a word which could be accurately interpreted today as "oppression", "injustice", "hate", "violence", and mankind's general inhumanity.

Griffith's narrative structure, though innovative, is uneven, because he gives more screen time to two of the four stories (the "modern" and the "Babylonian"). Equal time for three stories, thus deleting the fourth, might have worked better.

To me, the Babylonian story is the most interesting one because of its more complete coverage, and because of its elaborate costumes and spectacular sets. Even though there is no script, the viewer can easily discern the plot, which suggests that some of today's films might be just as effective, or more so, if screenwriters would downsize the dialogue.

What "Intolerance" offers most of all to contemporary viewers is a sense of perspective. Someone once said that despite the enormous advances in technology, society itself has advanced not at all. That may be true. In the eighty plus years since the film was released, technical advances in film-making have been obvious and impressive. But we are still plagued with the same old human demons of oppression, injustice, hate, violence, and ... intolerance.

How on Earth was D.W Griffith able to make this movie back in 1916? Back in the days when the audience were having a hard time focusing on two parallell stories, Griffith gave them four... This is a tremendous spectacle, way ahead of its time, and hardly dated at all. OK, the acting is a little bit over the edge (although Mae Marsh is a personal favourite of mine) and the subtitles are sometimes ridiculous, but the message that this movie brings is absolutely timeless. In fact, this is really the first movie with a vision, an idea. A major influence on Russian director Eisenstein, one has to wonder: Would there have been a Potemkin without this masterpiece? The Birth of a nation is in some ways superior to Intolerance, but for pure strength, innovation and boldness, Intolerance is unsurpassed and unsurpassable. The greatest movie of all times.

In 1915, D.W. Griffith's gave birth to modern cinema with "The Birth of a Nation", a giant leap that proved the remaining skeptics that the 20th century wouldn't do without the reel, that there was a time for Chaplin's gesticulations and a time for serious storytelling.

Of course, Chaplin's contribution is more valuable because he understood the universality of cinema more than any other filmmaker, let alone Griffith who made his film culminate with the glorification of the KKK. ¨People from all over the world would rather relate to the little tramp than any Griffith's character, but as I said in my "Birth of a Nation" review, without that seminal film, there wouldn't even be movies to contradict it.

And D.W. Griffith was actually the first to do so by making a humanistic anthology named "Intolerance: Love's Struggle Through the Ages", a three-hour epic relating four separate stories set at different historical times, but all converging toward the same hymn to intolerance, or denunciation of intolerance's effect through four major storylines: the fall of Babylon, the crucifixion of the Christ, the Bartholomew Day massacre and a contemporary tale with odd modern resonances. The four stories overlap throughout the film, punctuated with the same leitmotif of a mother "endless rocking the cradle", as to suggest the timeless and universal importance of the film.

The mother is played by an unrecognizable Lillian Gish but it's not exactly a film that invites you to admire acting, the project is so big, so ambitious on a simple intellectual level that it transcends every cinematic notion. It is really a unique case described as the only cinematic fugue (a word used for music), one of these films so dizzying in their grandeur that you want to focus on the achievements rather than the shortcomings, just like "Gone With the Wind" or more recently "Avatar". Each of the four stories would have been great and cinematically appealing in its own right, Griffith dares to tell the four of them using his trademark instinct for editing. Technically, it works.

And while I'm not surprised that he could pull such a stunt since he had already pushed the envelope in 1915, bmaking this "Intolerance" only one year after "The Birth of Nation" is baffling, especially since it was meant as an answer to the backlash he suffered from, it's obvious it wasn't pre-planned, so how he could make this in less than a year is extraordinary. I can't imagine how he got all these extras (three thousands), the recreations of ancient Babylon, of 16th century France, and still have time for a real story, but maybe that's revealing how eager he was to show that he wasn't the bigoted monster everyone accused him of, as if the scale of his sincerity had to be measured in terms of cinematic zeal. That the film flopped can even play as a sort of redemption in Griffith's professional arc.

But after the first hour, we kind of get the big picture and we understand that Griffith tells it like he means it. It works so well that the American Film Institute replaced the "Birth of a Nation" from the AFI Top 100 with "Intolerance" in the 10th anniversary update. But after watching the two of them, I believe they both belonged to the list as they're the two ideological sides of the same coin. But if one had to be kept, it would be the infamous rather than the famous, if only because the former is more 'enjoyable' in the sense that there's never a dull moment where you feel tempted to skip to another part. "Intolerance" had one titular key word: struggle, I struggled to get to the end, and even then, I had to watch it again because I couldn't stay focused. Indeed, what a challenging movie patience-wise!

This is a real orgy of set decorations that kind of loses its appeal near the second act, and while the first modern story is interesting because you can tell Griffith wanted to highlight the hypocrisy of our world's virtue posers, who try to make up for the very troubles they cause and use money for the most lamentable schemes, it might be too demanding to plug your mind to so many different stories. And when the climax starts with its collection of outbursts of violence, I felt grateful for finally rewarding my patience than enjoying the thrills themselves, especially since it doesn't hold up as well as the climactic sequence of "The Birth of a Nation". Or maybe we lost the attention span when it comes to silent movies, but there must be a reason the film flopped even at its time, maybe the abundance of notes and cardboards that makes the film look like a literary more than visual experience?

I guess "Intolerance" can be enjoyed sequence by sequence, by making as many halts as possible in that epic journey, but it's difficult to render a negative judgment for such a heavy loaded film. For my part, I'm glad I could finally watch and review all the movies from the American Film Institute's Top 100 and I appreciate its personal aspect in Griffith's career. Perhaps what the film does the best is to say more about the man than the director. His insistence on never giving names to his characters ("The Boy", "The Dear Guy"...) calling a mobster a "Musketeer" and all that vocabulary reveal his traditional and sentimental view of America, and maybe the rest of the world.

That's might be Griffith's more ironic trait, so modern on the field of technical film-making yet so old-fashioned in his vision, he's one hell of a storyteller and he handles the universal and historical approach of his film like a master, but when it comes to his personal vision, he struck me as the illustration of his own metaphor, like a good mother-figure endlessly rocking our cradle.

Of course, Chaplin's contribution is more valuable because he understood the universality of cinema more than any other filmmaker, let alone Griffith who made his film culminate with the glorification of the KKK. ¨People from all over the world would rather relate to the little tramp than any Griffith's character, but as I said in my "Birth of a Nation" review, without that seminal film, there wouldn't even be movies to contradict it.

And D.W. Griffith was actually the first to do so by making a humanistic anthology named "Intolerance: Love's Struggle Through the Ages", a three-hour epic relating four separate stories set at different historical times, but all converging toward the same hymn to intolerance, or denunciation of intolerance's effect through four major storylines: the fall of Babylon, the crucifixion of the Christ, the Bartholomew Day massacre and a contemporary tale with odd modern resonances. The four stories overlap throughout the film, punctuated with the same leitmotif of a mother "endless rocking the cradle", as to suggest the timeless and universal importance of the film.

The mother is played by an unrecognizable Lillian Gish but it's not exactly a film that invites you to admire acting, the project is so big, so ambitious on a simple intellectual level that it transcends every cinematic notion. It is really a unique case described as the only cinematic fugue (a word used for music), one of these films so dizzying in their grandeur that you want to focus on the achievements rather than the shortcomings, just like "Gone With the Wind" or more recently "Avatar". Each of the four stories would have been great and cinematically appealing in its own right, Griffith dares to tell the four of them using his trademark instinct for editing. Technically, it works.

And while I'm not surprised that he could pull such a stunt since he had already pushed the envelope in 1915, bmaking this "Intolerance" only one year after "The Birth of Nation" is baffling, especially since it was meant as an answer to the backlash he suffered from, it's obvious it wasn't pre-planned, so how he could make this in less than a year is extraordinary. I can't imagine how he got all these extras (three thousands), the recreations of ancient Babylon, of 16th century France, and still have time for a real story, but maybe that's revealing how eager he was to show that he wasn't the bigoted monster everyone accused him of, as if the scale of his sincerity had to be measured in terms of cinematic zeal. That the film flopped can even play as a sort of redemption in Griffith's professional arc.

But after the first hour, we kind of get the big picture and we understand that Griffith tells it like he means it. It works so well that the American Film Institute replaced the "Birth of a Nation" from the AFI Top 100 with "Intolerance" in the 10th anniversary update. But after watching the two of them, I believe they both belonged to the list as they're the two ideological sides of the same coin. But if one had to be kept, it would be the infamous rather than the famous, if only because the former is more 'enjoyable' in the sense that there's never a dull moment where you feel tempted to skip to another part. "Intolerance" had one titular key word: struggle, I struggled to get to the end, and even then, I had to watch it again because I couldn't stay focused. Indeed, what a challenging movie patience-wise!

This is a real orgy of set decorations that kind of loses its appeal near the second act, and while the first modern story is interesting because you can tell Griffith wanted to highlight the hypocrisy of our world's virtue posers, who try to make up for the very troubles they cause and use money for the most lamentable schemes, it might be too demanding to plug your mind to so many different stories. And when the climax starts with its collection of outbursts of violence, I felt grateful for finally rewarding my patience than enjoying the thrills themselves, especially since it doesn't hold up as well as the climactic sequence of "The Birth of a Nation". Or maybe we lost the attention span when it comes to silent movies, but there must be a reason the film flopped even at its time, maybe the abundance of notes and cardboards that makes the film look like a literary more than visual experience?

I guess "Intolerance" can be enjoyed sequence by sequence, by making as many halts as possible in that epic journey, but it's difficult to render a negative judgment for such a heavy loaded film. For my part, I'm glad I could finally watch and review all the movies from the American Film Institute's Top 100 and I appreciate its personal aspect in Griffith's career. Perhaps what the film does the best is to say more about the man than the director. His insistence on never giving names to his characters ("The Boy", "The Dear Guy"...) calling a mobster a "Musketeer" and all that vocabulary reveal his traditional and sentimental view of America, and maybe the rest of the world.

That's might be Griffith's more ironic trait, so modern on the field of technical film-making yet so old-fashioned in his vision, he's one hell of a storyteller and he handles the universal and historical approach of his film like a master, but when it comes to his personal vision, he struck me as the illustration of his own metaphor, like a good mother-figure endlessly rocking our cradle.

Everything about this movie is fascinating, even its numerous flaws. It is as ambitious a movie as has ever been made, and if you adjust for the era, it might also be the most lavish, expensive, and painstaking. Even today the scope and detail stand out, despite the many technical limitations in its era. Likewise, the enormous cast list contains many names that silent film fans will recognize at once, with well-known performers even in some of the minor roles. Then, you could write many pages about the stories, which are filled with weaknesses, but which are also so interesting that you never want to miss what will happen next.

The concept behind "Intolerance" is as enterprising as it gets: no fewer than four complete, independent story-lines, with the movie switching back-and-forth among them, not necessarily in consecutive order but with a definite plan in mind, all in order to get across the idea suggested by the title - that is, that intolerance of others' beliefs or lifestyles has been a destructive force throughout history. It is generally understood that there is a strong dose of defensiveness behind this plan, since the ideas promoted in Griffith's previous film had earned for him some severe and well-justified criticism. This personal motivation could well explain why "Intolerance" is often so overblown, and it also is interesting in light of the stories chosen to illustrate the main themes.

The two most straightforward stories - the persecution of the Huguenots in 16th century France, and the persecution of Jesus Christ by the religious leaders of his day - are also the most believable, and yet they do not seem to get quite the screen time or the lavish detail of the other two. The contemporary story may have been the most important to Griffith, and it is a full-scale melodrama, full of heavy-handed developments and very unlikely coincidences, yet certainly a story that will hold your attention. The Babylonian story is at once the strangest choice, the most extravagant, and the most fascinating of all. As history, it is as distorted as (or more so than) any of today's movies. Trying to pass off Belshazzar of Babylon as a model of justice and tolerance is just weird, and the entire historical scenario is at best an imaginative embellishment of the truth. But the involved story that Griffith tells in this setting is so exciting and entertaining that you just can't take your eyes away from it.

Much, much more could be said, but anyone with an interest in silent movies or in cinema history will want to watch it and draw his or her own conclusions. Whether you want to analyze the vast array of themes, events, and ideas, or whether you just want to sit back and enjoy a fascinating spectacle, the three hours fly by very quickly, and it's a movie you won't forget.

The concept behind "Intolerance" is as enterprising as it gets: no fewer than four complete, independent story-lines, with the movie switching back-and-forth among them, not necessarily in consecutive order but with a definite plan in mind, all in order to get across the idea suggested by the title - that is, that intolerance of others' beliefs or lifestyles has been a destructive force throughout history. It is generally understood that there is a strong dose of defensiveness behind this plan, since the ideas promoted in Griffith's previous film had earned for him some severe and well-justified criticism. This personal motivation could well explain why "Intolerance" is often so overblown, and it also is interesting in light of the stories chosen to illustrate the main themes.

The two most straightforward stories - the persecution of the Huguenots in 16th century France, and the persecution of Jesus Christ by the religious leaders of his day - are also the most believable, and yet they do not seem to get quite the screen time or the lavish detail of the other two. The contemporary story may have been the most important to Griffith, and it is a full-scale melodrama, full of heavy-handed developments and very unlikely coincidences, yet certainly a story that will hold your attention. The Babylonian story is at once the strangest choice, the most extravagant, and the most fascinating of all. As history, it is as distorted as (or more so than) any of today's movies. Trying to pass off Belshazzar of Babylon as a model of justice and tolerance is just weird, and the entire historical scenario is at best an imaginative embellishment of the truth. But the involved story that Griffith tells in this setting is so exciting and entertaining that you just can't take your eyes away from it.

Much, much more could be said, but anyone with an interest in silent movies or in cinema history will want to watch it and draw his or her own conclusions. Whether you want to analyze the vast array of themes, events, and ideas, or whether you just want to sit back and enjoy a fascinating spectacle, the three hours fly by very quickly, and it's a movie you won't forget.

Four storylines are followed. The first is set in the modern world, where The Dear One (Mae Marsh) and her beloved The Boy (Bobby Harron) are struggling to survive. He loses his job due to union striking after a pay cut mandated so that the company boss can fund his sister's charity work. That same charity takes away the Dear One's child, citing neglect, as the Boy is sent to jail after resorting to crime.

The Biblical "Judean" story recounts how intolerance led to the crucifixion of Jesus. This sequence is the shortest of the four.

The third story details the events of the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre of 1572 where Huguenot protestants were killed under orders of the Catholic royalty.

The fourth story is set in ancient Babylon, and deals with a religious struggle between different sects that leads to their conquest by the Persians.

Griffith's masterpiece is a marvel of narrative and structural complexity for the time, and the Babylon scenes are truly awe-inspiring in their scope and ambition. The story, in which instances of "intolerance" are illustrated throughout the ages, is a bit muddled and more than a little pretentious, but the visualization is second-to-none.

It's been put forth that Griffith made this as a sort of apologia for the racial insensitivity of his previous mega-hit The Birth of a Nation, but Griffith scholars disagree, and say that Griffith was never ashamed by the racist nature of his last movie, and that the intolerance that he was speaking out against was that which had been directed at him over that film (shades of our current political climate).

Regardless, this ended up being the most expensive film ever made up to that point, and was a major flop at the box office, from which Griffith never really recovered. The film now stands as a colossal achievement, and a precursor to historical epics to come. There are various versions in circulation.

The Biblical "Judean" story recounts how intolerance led to the crucifixion of Jesus. This sequence is the shortest of the four.

The third story details the events of the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre of 1572 where Huguenot protestants were killed under orders of the Catholic royalty.

The fourth story is set in ancient Babylon, and deals with a religious struggle between different sects that leads to their conquest by the Persians.

Griffith's masterpiece is a marvel of narrative and structural complexity for the time, and the Babylon scenes are truly awe-inspiring in their scope and ambition. The story, in which instances of "intolerance" are illustrated throughout the ages, is a bit muddled and more than a little pretentious, but the visualization is second-to-none.

It's been put forth that Griffith made this as a sort of apologia for the racial insensitivity of his previous mega-hit The Birth of a Nation, but Griffith scholars disagree, and say that Griffith was never ashamed by the racist nature of his last movie, and that the intolerance that he was speaking out against was that which had been directed at him over that film (shades of our current political climate).

Regardless, this ended up being the most expensive film ever made up to that point, and was a major flop at the box office, from which Griffith never really recovered. The film now stands as a colossal achievement, and a precursor to historical epics to come. There are various versions in circulation.

Le saviez-vous

- AnecdotesDuring filming of the battle sequences, many of the extras got so into their characters that they caused real injury to one another. At the end of one shooting day, a total of 60 injuries were treated at the production's hospital tent.

- GaffesOne of the early title cards in the Judean sequence refers to Jesus having been from "the carpenter shop in Bethlehem". Though he was born in Bethlehem, he worked with his father in a carpenter shop in Nazareth, which is why he was known as Jesus of Nazareth.

- Citations

Intertitle: When women cease to attract men, they often turn to reform as a second option.

- Crédits fousConstance Talmadge is credited as 'Georgia Pearce' for her performance as Marguerite de Valois in the French Story. She is credited under her own name in the role of The Mountain Girl in the Babylonian Story.

- Versions alternativesThe movie was officially restored in 1989 by Kevin Brownlow and David Gill for Thames Television. It was transferred from the best available 35mm materials, color-tinted per D.W. Griffith's intent, and contains a digitally recorded orchestral score by Carl Davis. This 176-minute version was released on video worldwide, but has never been telecast in the U.S.

- ConnexionsEdited into La Chute de Babylone (1919)

Meilleurs choix

Connectez-vous pour évaluer et suivre la liste de favoris afin de recevoir des recommandations personnalisées

- How long is Intolerance?Alimenté par Alexa

Détails

Box-office

- Budget

- 385 907 $US (estimé)

- Durée

- 2h 43min(163 min)

- Mixage

- Rapport de forme

- 1.33 : 1

Contribuer à cette page

Suggérer une modification ou ajouter du contenu manquant