La coquille et le clergyman

- 1928

- 40min

NOTE IMDb

7,0/10

2,4 k

MA NOTE

Obsédé par la femme d'un général, un ecclésiastique a d'étranges visions de mort et de luxure, luttant contre son propre érotisme.Obsédé par la femme d'un général, un ecclésiastique a d'étranges visions de mort et de luxure, luttant contre son propre érotisme.Obsédé par la femme d'un général, un ecclésiastique a d'étranges visions de mort et de luxure, luttant contre son propre érotisme.

- Réalisation

- Scénario

- Casting principal

Avis à la une

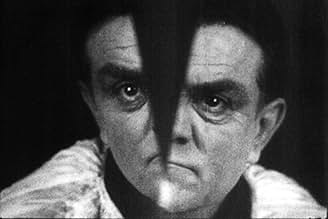

Surrealism as an art form, emerging in Europe after World War One, was designed to be illogical, but appealing to the subconscious. In cinema, there's debate as to what was the first surrealistic film in history. But there's no doubt filmmaker Germaine Dulac's February 1928 "The Seashell and the Clergyman" could qualify as one of the first containing elements of surrealism in it.

The 40-minute film, about a member of the clergy who lusts after the wife of a general and attempts to suppress such thoughts, is a whirlwind of images disconnected from any plot. Members of the British Board of Film Censors were totally confused by the piece. They wrote Dulac's production was "so cryptic as to be almost meaningless. If there is a meaning, it is doubtless objectionable." The board banned the film in the United Kingdom. Even the book's author "The Seashell and the Clergyman" was based on, Antonin Artaud, a top avant-garde writer, frowned upon Dulac's version.

History, however, has proven more kind to "The Seashell and the Clergyman." Once other surrealistic films were released, most notably 1929's "Un Chien Andalou," whose makers claim was the first in that category, it was apparent that elements found in those films sprung from the images of Dulac's. The French feminist filmmaker, who earlier produced the highly-regarded 1922 "The Smiling Madam Beudet," now is recognized by film historians as the pioneer of surrealism. Her stated goal was to create a new "art of vision," one that through symbolic images reveal a series of metaphors. It was meant to stir the viewer's psyche. Dulac's objective in "The Seashell" was to create an entirely new visual language on the screen, addressing her audience members' unconsciousness. In that, many film critics agree, she succeeded.

The 40-minute film, about a member of the clergy who lusts after the wife of a general and attempts to suppress such thoughts, is a whirlwind of images disconnected from any plot. Members of the British Board of Film Censors were totally confused by the piece. They wrote Dulac's production was "so cryptic as to be almost meaningless. If there is a meaning, it is doubtless objectionable." The board banned the film in the United Kingdom. Even the book's author "The Seashell and the Clergyman" was based on, Antonin Artaud, a top avant-garde writer, frowned upon Dulac's version.

History, however, has proven more kind to "The Seashell and the Clergyman." Once other surrealistic films were released, most notably 1929's "Un Chien Andalou," whose makers claim was the first in that category, it was apparent that elements found in those films sprung from the images of Dulac's. The French feminist filmmaker, who earlier produced the highly-regarded 1922 "The Smiling Madam Beudet," now is recognized by film historians as the pioneer of surrealism. Her stated goal was to create a new "art of vision," one that through symbolic images reveal a series of metaphors. It was meant to stir the viewer's psyche. Dulac's objective in "The Seashell" was to create an entirely new visual language on the screen, addressing her audience members' unconsciousness. In that, many film critics agree, she succeeded.

The predecessor of Un Chien Andalou and directed by the lone woman filmmaker of her time, La Coquille et le Clergyman is one of the most celebrated of French avant-garde movies of the '20s, partly because Antonin Artaud wrote the script, partly because the British censor of the time banned it with the legendary words 'If this film has a meaning, it is doubtless objectionable'. Artaud was reputedly unhappy with Dulac's realization of his scenario, and it's true that the story's anti-clericalism (a priest develops a lustful passion that plunges him into bizarre fantasies) is somewhat undermined by the director's determined visual lyricism. But the fragmentation of the narrative and the innovative imagery remain provocative, and the film is of course fascinating testimony to the currents of its time.

Obsessed with a general's woman (Genica Athanasiou), a clergyman (Alex Allin) has strange visions of death and lust, struggling against his own eroticism.

"Un chien andalou" is considered the first surrealist film, but its foundations in "The Seashell and the Clergyman" have been all but overlooked. However, the iconic techniques associated with surrealist cinema are all borrowed from this early film. Conversely, Alan Williams has suggested the film is better thought of as a work of or influenced by German expressionism.

I think this is why I absolutely adore this film. I'm enamored with German expressionism, and I love surreal film. This is the two combined, and the acting is superb. Anyone who loves "Un chien" really needs to check this one out.

"Un chien andalou" is considered the first surrealist film, but its foundations in "The Seashell and the Clergyman" have been all but overlooked. However, the iconic techniques associated with surrealist cinema are all borrowed from this early film. Conversely, Alan Williams has suggested the film is better thought of as a work of or influenced by German expressionism.

I think this is why I absolutely adore this film. I'm enamored with German expressionism, and I love surreal film. This is the two combined, and the acting is superb. Anyone who loves "Un chien" really needs to check this one out.

At first there seems to be some kind of science experiment. A potion is put from a vial into a pan by what looks to be a clergyman (?) and then a man in a General's uniform uses a sword to chop it down. The camera makes things look woozy, the frame and composition becoming warped and undone, like the feeling of going under or being drunk. We follow the Clergyman as he runs down a street (on his knees?) and then walks down a hall. There's also a woman, and the General is still there, but then... there's visions. He goes to another place mentally, perhaps, seeing a ship, water, waves, all sort of images that seem connected but disconnected at the same time. There's a room full of maids sweeping, then lined in formation. And then that 'Seashell' of the title - revealing (what else) boobs.

So much went into this film, the Seashell and the Clergyman, directed by Germain Dulac and written by one of the real-deal surrealists (and actor) Antonin Artuad, that I'm sure I could watch this five more times - and would want to - and get a different take on it each time. This preceded Un chien Andalou by a year, and yet I feel like these filmmakers and Bunuel/Dali were part of the same movement; whether Bunuel and Dali saw this film before they made their excursion is arguable, and I'd be curious to find out for sure (certainly the one moment where I went "Oh!" was when the clergyman reveals the seashell for the breasts - a similar shot happens in Andalou).

Yet it's impossible to make too many comparisons, because each surrealist goes about in their own way. This one has impressive, uncanny visual effects work for the time, mostly in ways of warping the frame - possibly by stretching the frame in post, or slow-motion in-camera. Then there's the simple act of one person being in a shot, and then the next someone popping up next to the actor through the jump-cut. Smoke is used to great effect at times, especially when violence occurs. Cinema tricks are plenty here, but what I took from the film is how it looks at the inner dream/mind-scape of such a person as the Clergyman. And perhaps this was Artaud's intention, maybe not (the British censors weren't sure what this was, but banned it anyway, possibly a gut reaction).

Why I read into it this way I'm not sure... actually, that's not totally true. It must be noted that this was directed not by a man (as Andalou) but a woman, and I think there's a different take on this because of that - a shot like the one with all the maids bustling about the room, doing their work almost like automatons, that has a woman's touch in a kind of satirical/absurd way. When I watch this film, I see a lot of sexualized imagery, a lot of repression, and it boiling over the surface. The version I watched on YouTube - with a great musical accompaniment that made it feel like a horror film in moments - had the air of an eerie land of nightmare and terror. The best surrealistic shorts has the stream-of-consciousness feel (think Deren or Bunuel or Man Ray), but this one especially has images that perhaps to make sense, in a Dream Logic sort of way, and if one were to follow the images as descriptions on paper, I'm sure it would read more like a poem.

It's a massively successful, deranged effort that can mean many things, but I have a feeling there's something strange about that Man of the Cloth...

So much went into this film, the Seashell and the Clergyman, directed by Germain Dulac and written by one of the real-deal surrealists (and actor) Antonin Artuad, that I'm sure I could watch this five more times - and would want to - and get a different take on it each time. This preceded Un chien Andalou by a year, and yet I feel like these filmmakers and Bunuel/Dali were part of the same movement; whether Bunuel and Dali saw this film before they made their excursion is arguable, and I'd be curious to find out for sure (certainly the one moment where I went "Oh!" was when the clergyman reveals the seashell for the breasts - a similar shot happens in Andalou).

Yet it's impossible to make too many comparisons, because each surrealist goes about in their own way. This one has impressive, uncanny visual effects work for the time, mostly in ways of warping the frame - possibly by stretching the frame in post, or slow-motion in-camera. Then there's the simple act of one person being in a shot, and then the next someone popping up next to the actor through the jump-cut. Smoke is used to great effect at times, especially when violence occurs. Cinema tricks are plenty here, but what I took from the film is how it looks at the inner dream/mind-scape of such a person as the Clergyman. And perhaps this was Artaud's intention, maybe not (the British censors weren't sure what this was, but banned it anyway, possibly a gut reaction).

Why I read into it this way I'm not sure... actually, that's not totally true. It must be noted that this was directed not by a man (as Andalou) but a woman, and I think there's a different take on this because of that - a shot like the one with all the maids bustling about the room, doing their work almost like automatons, that has a woman's touch in a kind of satirical/absurd way. When I watch this film, I see a lot of sexualized imagery, a lot of repression, and it boiling over the surface. The version I watched on YouTube - with a great musical accompaniment that made it feel like a horror film in moments - had the air of an eerie land of nightmare and terror. The best surrealistic shorts has the stream-of-consciousness feel (think Deren or Bunuel or Man Ray), but this one especially has images that perhaps to make sense, in a Dream Logic sort of way, and if one were to follow the images as descriptions on paper, I'm sure it would read more like a poem.

It's a massively successful, deranged effort that can mean many things, but I have a feeling there's something strange about that Man of the Cloth...

Germaine Dulac was no ordinary French female film-director. She was Avante-Garde and radical in her film-making which did not include a laugh track or sound. Everything was visual and her silent classics were visuals to be appreciated and understood by all of us. There was a reason that so many people saw the same movie numerous times during that era. First, it was very inexpensive and second, you needed to revisit and see the film again and again until you saw it completely. That's how films once were, films were visual masterpieces and in Dulac's case, she helped reshape the role of women in films to include more than just being an actress. She was the producer, director, and writer. She was many things to many people on film sets in France. Film was new and fresh invention that those of us who seek to learn more about art should watch Dulac's classic.

Le saviez-vous

- AnecdotesThe British Board of Film Censors banned this film in the UK in 1927, saying, "This film is so obscure as to have no apparent meaning. If there is a meaning, it is doubtless objectionable."

- ConnexionsEdited into Women Who Made the Movies (1992)

Meilleurs choix

Connectez-vous pour évaluer et suivre la liste de favoris afin de recevoir des recommandations personnalisées

Détails

- Date de sortie

- Pays d’origine

- Site officiel

- Langue

- Aussi connu sous le nom de

- The Seashell and the Clergyman

- Lieux de tournage

- Société de production

- Voir plus de crédits d'entreprise sur IMDbPro

- Durée

- 40min

- Couleur

- Mixage

- Rapport de forme

- 1.33 : 1

Contribuer à cette page

Suggérer une modification ou ajouter du contenu manquant