NOTE IMDb

7,2/10

1,2 k

MA NOTE

Ajouter une intrigue dans votre langueA unique documentary on the notorious S-21 prison, today the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, with testimony by the only surviving prisoners and former Khmer Rouge guards.A unique documentary on the notorious S-21 prison, today the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, with testimony by the only surviving prisoners and former Khmer Rouge guards.A unique documentary on the notorious S-21 prison, today the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, with testimony by the only surviving prisoners and former Khmer Rouge guards.

- Réalisation

- Scénario

- Casting principal

- Récompenses

- 13 victoires et 4 nominations au total

Nhem En

- Self - Photographer

- (as Nhiem Ein)

Avis à la une

I have read the other comments on here and think that many people missed the point. This documentary illustrated the banality of evil very powerfully; it did not preach or try to shove the makers' opinion down the viewers' throat, like SO many other so-called documentaries do. This is not one of those "documentaries" which show edited footage and historical footage as a mere backdrop to put forth someone's opinion. That's what made it so powerful, to see the people who committed this incomprehensible evil and those that suffered it asking their own questions, trying to make sense of it all, trying to justify it, analyzing their roles in real time as the cameras roll. It was very evident that this was the first time many of them had questioned themselves on what they had done. The repetitive re-enactment and explanation of the guard's day to day activities were horrific in their normality. Even after all these years, after all that's happened, these men had no qualms about showing the world their routines, making it obvious that they don't equate their actions directly to the effects it had on their fellow country men and women. One has to remember that the guards were brain washed and indoctrinated by the communists at a very young age. This can be directly equated with what's happening in the world today with militant Islam. They're creating their own amoral killers and fanatics by indoctrinating and brain washing children. If nothing else, this documentary shows how once indoctrinated at a young age with fanatical ideology, all that remains for the rest of that persons life is an empty shell incapable of comprehending basic humanity.

I got to see this film at a special screening at the Alliance France in Manila, the French embassy's cultural center. Many of the small audience in the screening room (the copy screened was a DVD) did not bother to finish the film.

For myself, I found the film a flawed but powerful experience. One major flaw is, as other reviewers have pointed out, its cold opening. In other words, it assumes you already know what S-21 is and what the Khmer Rouge are. Without this valuable background information, which the documentary does not provide, the viewers may be lost at first.

It is also kind of dry, since the movie takes place only within the walls of S-21, involving only the few survivors of the prison and some of their former jailers. Essentially they spent the entire film talking. There is no attempt on the part of the director to make it more cinematic.

However, the patient viewer will soon find him or herself immersed in the horrors of the Khmer Rouge as detail after detail of the atrocities committed in the prison emerge. The handful of survivors go through mementos of the prison, including logbooks detailing the tortures committed against inmates, along with some of those who worked in the prison, including a guard and a doctor. The question the survivors constantly ask their former jailers is: How? How could you do these things? And they have no answers.

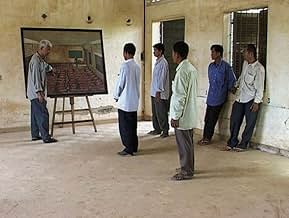

The most chilling scenes in the film involve a former prison guard recreating in an empty cell the routine he took with the prisoners, bringing them food, water or a container to pee in, threatening them with a beating if they don't go to sleep or cry too loudly. Its throughly disturbing to see, even if there are no actual prisoners there.

S-21 is not for everybody. But if you're already familiar with the Khmer Roune and this part of Cambodian history, the documentary may be worth watching to deepen your understanding of this dark period of history.

For myself, I found the film a flawed but powerful experience. One major flaw is, as other reviewers have pointed out, its cold opening. In other words, it assumes you already know what S-21 is and what the Khmer Rouge are. Without this valuable background information, which the documentary does not provide, the viewers may be lost at first.

It is also kind of dry, since the movie takes place only within the walls of S-21, involving only the few survivors of the prison and some of their former jailers. Essentially they spent the entire film talking. There is no attempt on the part of the director to make it more cinematic.

However, the patient viewer will soon find him or herself immersed in the horrors of the Khmer Rouge as detail after detail of the atrocities committed in the prison emerge. The handful of survivors go through mementos of the prison, including logbooks detailing the tortures committed against inmates, along with some of those who worked in the prison, including a guard and a doctor. The question the survivors constantly ask their former jailers is: How? How could you do these things? And they have no answers.

The most chilling scenes in the film involve a former prison guard recreating in an empty cell the routine he took with the prisoners, bringing them food, water or a container to pee in, threatening them with a beating if they don't go to sleep or cry too loudly. Its throughly disturbing to see, even if there are no actual prisoners there.

S-21 is not for everybody. But if you're already familiar with the Khmer Roune and this part of Cambodian history, the documentary may be worth watching to deepen your understanding of this dark period of history.

10ubu-3

This is a great movie about the Cambodian genocide. Refusing any sensational or sentimental approach, it is just made out of testimonies, and patiently, slowly tries to understand how such a thing could happen. The mechanics of the Khmer Rouge crimes, the paranoiac will to obtain (by torture) a "reason" (completely absurd) to kill their victims is terrifying. And testimony's of the torturers are striking of refusal. Patience, the intelligence and the firmness of one of the rare surviving victims give again fortunately confidence in humanity. This movie is made on a similar approach to Claude Lanzmann's "Shoah". Which means to place the testimonies in the center, and refusing any reconstitution or archive images. Maybe the only way to speak about such an event ?

Before my recent visit to Cambodia which included a short tour of S21, I did some reading on the prison and the complex events that led to its development and operation during the Democratic Kampuchea (Pol Pot) regime.

This movie did a remarkable job filling in my sense of S21 that was not otherwise possible to experience through reading or even touring the prison. For example, interviews with two of the only seven survivors out of over 14,000 prisoners detained and killed at S21 was remarkable by itself as was the opening sequence of a former guard discussing the morality of his role with parents who no doubt felt the full brunt of the Khmer Rouge's brutality, yet survived.

Seeing details such as the private cells, photography apparatus, the typewriters that clacked away to record prisoners' tortured confessions, and the former guards' convincing reenactment of their job as teenage guards at this grisly place was at the same time deeply disturbing and satisfying in improving my understanding of this total institution. The very instruments of dehumanization - ammunition buckets used for toilets, the bare tile floors prisoners were shackled to between interrogations and torture, the windows open to mosquitoes and vermin allowed to feast on the prisoners - are both stark and subtle in their presentation.

Those who expect anything more than a rudimentary understanding of this infamous killing machine may be disappointed. Seeing this movie was at least as valuable as seeing the prison in person. I especially recommend it for anyone who has visited S21 or expects to visit Cambodia.

This movie did a remarkable job filling in my sense of S21 that was not otherwise possible to experience through reading or even touring the prison. For example, interviews with two of the only seven survivors out of over 14,000 prisoners detained and killed at S21 was remarkable by itself as was the opening sequence of a former guard discussing the morality of his role with parents who no doubt felt the full brunt of the Khmer Rouge's brutality, yet survived.

Seeing details such as the private cells, photography apparatus, the typewriters that clacked away to record prisoners' tortured confessions, and the former guards' convincing reenactment of their job as teenage guards at this grisly place was at the same time deeply disturbing and satisfying in improving my understanding of this total institution. The very instruments of dehumanization - ammunition buckets used for toilets, the bare tile floors prisoners were shackled to between interrogations and torture, the windows open to mosquitoes and vermin allowed to feast on the prisoners - are both stark and subtle in their presentation.

Those who expect anything more than a rudimentary understanding of this infamous killing machine may be disappointed. Seeing this movie was at least as valuable as seeing the prison in person. I especially recommend it for anyone who has visited S21 or expects to visit Cambodia.

A few years ago, I find myself travelling through South-East Asia, at one point trying to piece together a baffling series of events that resulted in the genocide of a third of Kampuchea, or Cambodia as we now call it.

I read as much as I can, and try to speak to survivors. But the eyes of family members well up with tears. The inexpressible grief is barely contained. Out of respect, I desist.

Some time later, I see this film by internationally acclaimed human rights director, Rithy Panh. He has a better reason for asking – he survived the massacre. His work, unlike my simple desire for knowledge, would provide momentum for confessions and now a war crimes tribunal. At the 'Killing Fields' outside Phnom Penh is a tree against which children had their brains bashed out. In the film, a guard explains how parents would be separated from each other, and from their children, to minimise fuss. The adults were told not to worry: they were going to a new home. They were then blindfolded for 'security reasons' and, ammunition being scarce, hit on the back of the neck with metal bars before being cast into a pit.

Executions followed three levels of torture at S.21, a school building in Phnom Penh converted into a concentration camp (and now a memorial visitors centre). Details are so hideous – humans packed like abattoir carcasses, and systematic torture, that you could be forgiven for suspecting truth has been embroidered. Except for one fact. Meticulous records of every victim were kept. Each non-person, each beating, each flaying of skin, each removal of fingernails, chemical and electrical abuses, rape. Precise details of prisoners chained to iron bars to sleep, crammed together top-to-toe, living sharing a sardine-row with the dead.

Rithy Panh's master stroke brings together S.21 survivors (two of the existing three) and former guards and torturers. He encourages them to talk. To find answers. One of the hardest things, even now, is these perpetrators see themselves also as victims. They joined Pol Pot's Khmer Rouge for what seemed like all the right reasons. Once inducted, they were brainwashed, indoctrinated and trapped. Deviation meant the same fate as those they flayed alive. Most were youths at the time, easily manipulated. But, how can you forgive and move on, when no-one will admit wrong-doing? Even Pol Pot blamed the people he left in charge.

Men joined the Khmer Rouge because their villages were being repeatedly bombed. With their government's approval. The much loved Prince Sihanouk had been ousted in a coup. Lon Nol, an ineffective, U.S.-backed ruler, was forcibly installed in his place. Lon Nol gave America (under Johnson and Nixon) 'permission' for what became the largest bombing campaign in human history. Two and three-quarter million tons of bombs – the revised figure released by the Clinton administration – was more than the total dropped by all the allies in the whole of World War Two (which only came to two million, even including Hiroshima and Nagasaki). Whole areas of the country became pock-marked, aerial chemical deforestation destroyed livelihoods and created famine and disease. Thousands killed, many more permanently displaced. The Khmer Rouge leaders kept their extreme agenda – a form of rural, back-to-basics communism – completely secret until they were installed in power. Then the purges started. Lon Nol supporters were followed to the grave by academics or anyone tainted with 'western' ideas. Anyone opposing Pol Pot, or whose name was elicited under extreme torture. The population was turned out of the cities, dying of starvation. With no-one else to purge, the despots found traitors to execute its own members.

Kampuchea's leading doctor, Swiss born Beat Richner, adamantly told me that without American intervention – which had been aimed ironically at stopping communism in the region – there would have been no Khmer Rouge. No Pol Pot victory. Richner worked in Kampuchea before, during and after Pol Pot, and his coal-face assessment agrees with most historians. But it is controversial: the U.S. military claim that Pol Pot would have won anyway. Ordinary Cambodians are still grieving rather than blaming. Rithy Panh's film exposes horror without finger-pointing. There are no 'lessons to be learnt.' Millions died – estimates say around a third of the population, two to three million. (And this in a country smaller than Great Britain. As a benchmark comparison, Hitler exterminated six million Jews .) While Panh documents the existence of atrocities, he does little to substantiate the bigger picture, which has to be gleaned elsewhere or from casual remarks of the former guards.

Rithy Panh's film, S.21 – The Khmer Rouge Killing Machine, has no real ax to grind – in the tradition of best documentary, it simply tries to provide a window. While it is powerful evidence, many viewers might find it emotionally less satisfying than more box-office friendly film by Roland Joffé, The Killing Fields, which (symbolically) suggests the West's responsibility by the journalist who 'uses' his Cambodian friend for his own ends, and also has more of a story. Either way, it is a country that makes me ashamed to be a Westerner. Yet Cambodians have more to worry about than my sense of emotional well-being. Avoiding hunger, or the thousands of landmines that still litter their country. In Joffe's film, an American journalist travels to a Red Cross camp to be reunited with a Cambodian colleague he deserted to his fate. "Do you forgive me?" he asks. The Cambodian answers with a smile, "Nothing to forgive, Sydney, nothing to forgive." Although it won many awards, Panh's movie is rarely shown outside of Cambodia. There you can pick it up for about $3. From one of the many maimed or desperate hawkers that haunt the road outside Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum. This place formerly known as Security Prison 21, or 'S.21' for short, still has living ghosts. The film just tells us where they came from.

I read as much as I can, and try to speak to survivors. But the eyes of family members well up with tears. The inexpressible grief is barely contained. Out of respect, I desist.

Some time later, I see this film by internationally acclaimed human rights director, Rithy Panh. He has a better reason for asking – he survived the massacre. His work, unlike my simple desire for knowledge, would provide momentum for confessions and now a war crimes tribunal. At the 'Killing Fields' outside Phnom Penh is a tree against which children had their brains bashed out. In the film, a guard explains how parents would be separated from each other, and from their children, to minimise fuss. The adults were told not to worry: they were going to a new home. They were then blindfolded for 'security reasons' and, ammunition being scarce, hit on the back of the neck with metal bars before being cast into a pit.

Executions followed three levels of torture at S.21, a school building in Phnom Penh converted into a concentration camp (and now a memorial visitors centre). Details are so hideous – humans packed like abattoir carcasses, and systematic torture, that you could be forgiven for suspecting truth has been embroidered. Except for one fact. Meticulous records of every victim were kept. Each non-person, each beating, each flaying of skin, each removal of fingernails, chemical and electrical abuses, rape. Precise details of prisoners chained to iron bars to sleep, crammed together top-to-toe, living sharing a sardine-row with the dead.

Rithy Panh's master stroke brings together S.21 survivors (two of the existing three) and former guards and torturers. He encourages them to talk. To find answers. One of the hardest things, even now, is these perpetrators see themselves also as victims. They joined Pol Pot's Khmer Rouge for what seemed like all the right reasons. Once inducted, they were brainwashed, indoctrinated and trapped. Deviation meant the same fate as those they flayed alive. Most were youths at the time, easily manipulated. But, how can you forgive and move on, when no-one will admit wrong-doing? Even Pol Pot blamed the people he left in charge.

Men joined the Khmer Rouge because their villages were being repeatedly bombed. With their government's approval. The much loved Prince Sihanouk had been ousted in a coup. Lon Nol, an ineffective, U.S.-backed ruler, was forcibly installed in his place. Lon Nol gave America (under Johnson and Nixon) 'permission' for what became the largest bombing campaign in human history. Two and three-quarter million tons of bombs – the revised figure released by the Clinton administration – was more than the total dropped by all the allies in the whole of World War Two (which only came to two million, even including Hiroshima and Nagasaki). Whole areas of the country became pock-marked, aerial chemical deforestation destroyed livelihoods and created famine and disease. Thousands killed, many more permanently displaced. The Khmer Rouge leaders kept their extreme agenda – a form of rural, back-to-basics communism – completely secret until they were installed in power. Then the purges started. Lon Nol supporters were followed to the grave by academics or anyone tainted with 'western' ideas. Anyone opposing Pol Pot, or whose name was elicited under extreme torture. The population was turned out of the cities, dying of starvation. With no-one else to purge, the despots found traitors to execute its own members.

Kampuchea's leading doctor, Swiss born Beat Richner, adamantly told me that without American intervention – which had been aimed ironically at stopping communism in the region – there would have been no Khmer Rouge. No Pol Pot victory. Richner worked in Kampuchea before, during and after Pol Pot, and his coal-face assessment agrees with most historians. But it is controversial: the U.S. military claim that Pol Pot would have won anyway. Ordinary Cambodians are still grieving rather than blaming. Rithy Panh's film exposes horror without finger-pointing. There are no 'lessons to be learnt.' Millions died – estimates say around a third of the population, two to three million. (And this in a country smaller than Great Britain. As a benchmark comparison, Hitler exterminated six million Jews .) While Panh documents the existence of atrocities, he does little to substantiate the bigger picture, which has to be gleaned elsewhere or from casual remarks of the former guards.

Rithy Panh's film, S.21 – The Khmer Rouge Killing Machine, has no real ax to grind – in the tradition of best documentary, it simply tries to provide a window. While it is powerful evidence, many viewers might find it emotionally less satisfying than more box-office friendly film by Roland Joffé, The Killing Fields, which (symbolically) suggests the West's responsibility by the journalist who 'uses' his Cambodian friend for his own ends, and also has more of a story. Either way, it is a country that makes me ashamed to be a Westerner. Yet Cambodians have more to worry about than my sense of emotional well-being. Avoiding hunger, or the thousands of landmines that still litter their country. In Joffe's film, an American journalist travels to a Red Cross camp to be reunited with a Cambodian colleague he deserted to his fate. "Do you forgive me?" he asks. The Cambodian answers with a smile, "Nothing to forgive, Sydney, nothing to forgive." Although it won many awards, Panh's movie is rarely shown outside of Cambodia. There you can pick it up for about $3. From one of the many maimed or desperate hawkers that haunt the road outside Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum. This place formerly known as Security Prison 21, or 'S.21' for short, still has living ghosts. The film just tells us where they came from.

Le saviez-vous

- ConnexionsEdited into Rendez-vous avec Pol Pot (2024)

Meilleurs choix

Connectez-vous pour évaluer et suivre la liste de favoris afin de recevoir des recommandations personnalisées

- How long is S21: The Khmer Rouge Killing Machine?Alimenté par Alexa

Détails

- Date de sortie

- Pays d’origine

- Langues

- Aussi connu sous le nom de

- S21: The Khmer Rouge Killing Machine

- Lieux de tournage

- Sociétés de production

- Voir plus de crédits d'entreprise sur IMDbPro

Box-office

- Montant brut aux États-Unis et au Canada

- 22 606 $US

- Week-end de sortie aux États-Unis et au Canada

- 7 302 $US

- 23 mai 2004

- Montant brut mondial

- 23 550 $US

- Durée1 heure 41 minutes

- Couleur

Contribuer à cette page

Suggérer une modification ou ajouter du contenu manquant

Lacune principale

By what name was S21, la machine de mort khmère rouge (2003) officially released in India in English?

Répondre