VALUTAZIONE IMDb

7,2/10

8289

LA TUA VALUTAZIONE

Una famiglia con non pochi problemi è costretta ad affrontare la situazione quando qualcosa va terribilmente storto alla desolata postazione militare del figlio.Una famiglia con non pochi problemi è costretta ad affrontare la situazione quando qualcosa va terribilmente storto alla desolata postazione militare del figlio.Una famiglia con non pochi problemi è costretta ad affrontare la situazione quando qualcosa va terribilmente storto alla desolata postazione militare del figlio.

- Regia

- Sceneggiatura

- Star

- Premi

- 21 vittorie e 25 candidature totali

Yonatan Shiray

- Jonathan

- (as Yonathan Shiray)

Itay Exlroad

- Dancer Soldier

- (as Etay Axelroad)

Arie Tcherner

- High Ranking Officer

- (as Aryeh Cherner)

Recensioni in evidenza

This highly acclaimed drama from Israel is a thoughtful and deep reflection on how we perceive of the scars that grief and guilt can leave on us. The film follows a patriarch and his wife who are told at the beginning of the film by Israeli army officers that their son was killed in the line of duty. These two parents begin to embark on a seemingly hellish grieving process...for the first 30 minutes. I won't give away what happens next, but the film ends up taking a variety of unique twists and turns through three distinct parts similar to that of a triptych-style narrative. It's not quite what you think it is, that's for sure.

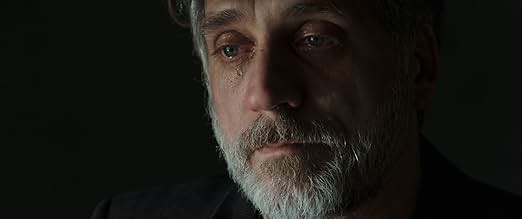

The acting in the film is consistently excellent, particularly the performance of the father. He manages to engage the audience in his seething feelings of sadness and an almost-primal sensation of rage, while still feeling uniquely down-to-earth and relatable. This is an almost impossible trick to pull off. Samuel Maoz clearly knows how to write thoughtful analysis of the society and people of Israel, with a clockwork level of precision--and props to him for that. The pacing in the film's three acts, however, could have been improved and can feel somewhat erratic in the movie's second half. Additionally, the finale of the movie is done in a somewhat peculiar manner that falls a bit short of what would most satisfy the viewer in terms of wrapping up the story. Still, I definitely recommend "Foxtrot" to those interested and thought this was quite a well-made film at the end of the day. 7.5/10

The acting in the film is consistently excellent, particularly the performance of the father. He manages to engage the audience in his seething feelings of sadness and an almost-primal sensation of rage, while still feeling uniquely down-to-earth and relatable. This is an almost impossible trick to pull off. Samuel Maoz clearly knows how to write thoughtful analysis of the society and people of Israel, with a clockwork level of precision--and props to him for that. The pacing in the film's three acts, however, could have been improved and can feel somewhat erratic in the movie's second half. Additionally, the finale of the movie is done in a somewhat peculiar manner that falls a bit short of what would most satisfy the viewer in terms of wrapping up the story. Still, I definitely recommend "Foxtrot" to those interested and thought this was quite a well-made film at the end of the day. 7.5/10

I've been expecting to see faster happenings in the movie, but no, I did not. As one drama, it is good in those segments where you can follow the main character's expressions, but on the other hand it is a bit boring because he is not the only character in it and almost all the rest are unconvincing actors. From time to time a director gives us pieces of black humor and that intention drives us not to be rigorous in giving comments. It is specifically in those scenes with four soldiers in shipping container, that is slowly sinking into the muck, and in which they are located to be while guarding the border. The best two things of the movie are those shots made from above and that little cartoon where we can see the story about what happened in the past and why. From my point of view, it is worth seeing, but it is not the perfect masterpiece as we wanted to see.

Greetings again from the darkness. The most dreaded knock on the door. Every parent or spouse of someone who has served their country during war time fully understands that indescribable feeling of opening the door and seeing uniformed soldiers waiting to deliver the worst possible news. That knock is how Israeli writer/director Samuel Maoz (LEBANON, 2009) chooses to open his film. Knowing her son Daniel is dead sends Daphna (Sarah Adler) into hysterics, and the experienced messengers know to administer something to help her relax and sleep. Her husband Michael (Lior Ashkenazi, FOOTNOTE) stands stunned, mostly unable to respond.

What follows is one of the most stunning first Act performances we've seen on the big screen. That is not hyperbole. Mr. Ashkenazi is remarkable over the first approximately 20 minutes as a parent in shock, experiencing devastating grief. The news is debilitating to his physical and mental being. Additionally, the filmmaking during this segment is quite something to behold. The close-ups add a heavy dose of humanity, while the terrific overhead camera angle presents Michael as trapped, while also adding to the disorientation that is so key. The one-hour alarm set to remind him to "drink some water" would be humorous if not for the fact that its structure prevents the man from totally breaking down.

The second Act takes us away from Daphna's and Michael's contemporary Tel Aviv apartment and plops us into a remote military outpost where 4 young soldiers are charged with guarding a road passage. Thanks to this boring assignment, the young men find ways of adding interest to their days: timing canned goods that roll down the ever-increasing slope of their sinking-in-the-muck domicile container, raising the bar for the periodic camel that lopes by, and giving the rare passers-by a bit of a hard time as their ID's are checked. 'Of course, this is war territory, so when something goes wrong, it goes terribly and horrifically wrong.

Our final Act takes us back to the original apartment as Michael, Daphna and their daughter are working to reconcile their feelings and somehow re-assemble the pieces of their shattered lives ... though the shifts from that heartbreaking first Act are what sets the script apart from so many movies. Cinematographer Giora Bejach continues the exemplary camera work during this curious segment that leaves us feeling somewhat uncertain at first.

This family is stuck in the war that never ends. Like so many in the area, they carry burdens, guilt and grief that, like the war, also never ends. That first Act is transcendent filmmaking and acting, and the three acts work together as a prime example of the melding of visual and emotional storytelling. Most of the film takes place in one of two locales, and it's the subtleties in each shot that tell us what we must know. And yes, the foxtrot dance does play a role, but like most of this film, it's best discovered on your own.

What follows is one of the most stunning first Act performances we've seen on the big screen. That is not hyperbole. Mr. Ashkenazi is remarkable over the first approximately 20 minutes as a parent in shock, experiencing devastating grief. The news is debilitating to his physical and mental being. Additionally, the filmmaking during this segment is quite something to behold. The close-ups add a heavy dose of humanity, while the terrific overhead camera angle presents Michael as trapped, while also adding to the disorientation that is so key. The one-hour alarm set to remind him to "drink some water" would be humorous if not for the fact that its structure prevents the man from totally breaking down.

The second Act takes us away from Daphna's and Michael's contemporary Tel Aviv apartment and plops us into a remote military outpost where 4 young soldiers are charged with guarding a road passage. Thanks to this boring assignment, the young men find ways of adding interest to their days: timing canned goods that roll down the ever-increasing slope of their sinking-in-the-muck domicile container, raising the bar for the periodic camel that lopes by, and giving the rare passers-by a bit of a hard time as their ID's are checked. 'Of course, this is war territory, so when something goes wrong, it goes terribly and horrifically wrong.

Our final Act takes us back to the original apartment as Michael, Daphna and their daughter are working to reconcile their feelings and somehow re-assemble the pieces of their shattered lives ... though the shifts from that heartbreaking first Act are what sets the script apart from so many movies. Cinematographer Giora Bejach continues the exemplary camera work during this curious segment that leaves us feeling somewhat uncertain at first.

This family is stuck in the war that never ends. Like so many in the area, they carry burdens, guilt and grief that, like the war, also never ends. That first Act is transcendent filmmaking and acting, and the three acts work together as a prime example of the melding of visual and emotional storytelling. Most of the film takes place in one of two locales, and it's the subtleties in each shot that tell us what we must know. And yes, the foxtrot dance does play a role, but like most of this film, it's best discovered on your own.

As others have pointed out, this is a 3-act film. Act 1 provides a chilling view of the military precision of the Israeli military's process for informing a family of a tragedy. Act 2 provides a view of Foxtrot outpost, a checkpoint guarding some deserted road. There is the general boredom, combined with occasions of high anxiety, where any car to be checked could have suicide bombers. In Act 3, the family's unsuccessful attempt to see their son's body leads to more drama, with an ending that I consider too neat - hence my low score on the movie.

Part satirical allegory, part surrealist indictment, Foxtrot finds writer/director Samuel Maoz working with similar themes as he did in Lebanon (2009); the ridiculous nature of war, the desensitisation of youth during wartime, the futility and meaninglessness of giving one's life in the service of one's country. However, whereas Lebanon was set during the 1982 Lebanon War, and shot entirely from inside a Centurion tank, Foxtrot is set in the present day, and expands Moaz's thematic concerns to take in the grief and anguish of those who have lost children to military service. Much like Lebanon, Foxtrot is an intensely political film, and much like Lebanon, Foxtrot has met with controversy and condemnation in Maoz's native Israel. Whereas Lebanon was accused of attempting to dissuade young men from joining the Israel Defense Forces (IDF), Foxtrot has been attacked for slandering the moral character of the IDF. A meditative and contemplative piece, heavy on metaphors, for the most part, the film hinges on non-action and passivity - the characters don't so much drive events, as events happen to them. Indeed, this is another of the film's themes - our inability to control fate (or, depending on your outlook, random chance). As with Lebanon, Maoz displays extraordinary technical proficiency and control of the medium, with the film as aesthetically impressive as it is politically divisive. A savage condemnation of both a national psyche and a military mindset that trades on the most binary of them-versus-us dichotomies and consciously strives to blur the line between personal honour and political ideology, Foxtrot is not always an easy watch, and it's rarely what you would call "entertaining", but it's undeniably a brilliantly made and deeply passionate film.

Divided into three distinct sections, the film tells the story of Michael Feldman (a superb Lior Ashkenazi), who receives word that his son Jonathan, a conscript in the IDF, has been killed "in the line of duty". Devastated, he begins to ask questions - how was Jonathan killed, where was he stationed, is there a body - none of which are met with a straight answer. However, several hours later, Michael and his wife Dafna (Sarah Adler) are told Jonathan is still alive; a Jonathan Feldman was killed, but it was a different Jonathan Feldman. The film then jumps several days back to a forlorn desert checkpoint on Israel's northern border (codename Foxtrot) manned by a group of wet-behind-the-ears soldiers, including Jonathan Feldman (Yonatan Shiray). The most action the group see is raising the barrier to let a camel amble through and checking the IDs of the few Palestinians who pass by. Indeed, they are more interested in the fact that the shipping container in which they sleep is slowly sinking into the sand than in anything military-related. However, when a mistake whilst checking the IDs of a group of Palestinians leads to tragedy, Jonathan comes to learn just how ruthlessly political the IDF can be. Without spoiling anything, the third section, which is kind of an extended coda, then returns to Michael and Dafna's apartment, six months after the opening scenes.

In Foxtrot, Maoz constructs an allegory through which he deconstructs Israeli national myths and self-aggrandising narratives. Interrogating what he sees as a culture of denial born from a reluctance to deal with the morality and sustainability of being an occupying force, the film gets a lot of mileage out of the metaphor of the foxtrot - a dance where no matter where you go, if you follow the steps correctly, you end up back at the starting position. Applied to Israel, or indeed, any nation, Maoz is suggesting that without taking great care, countries will repeat the errors of the past, ending up exactly where they once were. The film depicts three generations of Feldmans (Michael's mother (Karin Ugowski), a Holocaust survivor now suffering from dementia, Michael himself, and Jonathan) dancing the foxtrot (literally in Michael and his mother's cases), either unwilling or unable to face up to the country's violent and traumatic past. Speaking to the Globe and Mail, Maoz explains, "Foxtrot deals with the open wound or bleeding soul of Israeli society. We dance the foxtrot; each generation tries to dance it differently but we all end up at the same starting point", whilst he tells the LA Times, "the roadblock is a microcosm of a society - any society - that has its perception distorted by a past trauma."

In a more concrete sense, in two scenes at Foxtrot, the film examines the casual sadism, unspoken racism, and braggadocious machoism that can arise from serving in the armed forces of a country perpetually at war. In the first (arguably the best scene in the film), the soldiers make a Palestinian couple stand in the pouring rain whilst their antiquated computer checks the couple's IDs. Obviously dressed for a formal night (he is in a tuxedo, she in an elegant dress), by the time the soldiers clear them to pass, their clothes are destroyed, as is her hair, and her makeup is ruined, with the soldiers even making her empty the contents of her purse onto the ground. The scene is brilliantly staged, agonisingly realistic, and takes place in real-time, with Maoz concentrating on the couple looking at one another across the roof of the car, conveying agonised helplessness, compromised innocence, understandable belligerency, and, most saliently, abject humiliation. It's a masterclass in dialogue-free storytelling, and deeply political storytelling at that. In the second scene, the soldiers act with violent impunity against a car of young Palestinians, although the act of violence itself arises from a mistake.

Aesthetically, as with Lebanon, Foxtrot is fascinatingly staged. For starters, Maoz shoots each of the three sections differently, but in ways tightly tied to their thematic focus; the first is highly restrictive, trapping us in the confined ideological headspace of the Feldmans, with the intense emotionality constantly threatening to boil over; the vast wide-open vistas of the second part contrast sharply with the confinement of the first, with the entire section threaded through with surrealism and even a hint of magic realism; the third section is darker than the others (in a literal sense), with a stark visual design that emphasises only those elements that are important to the scene. The Feldman apartment itself is extremely angular, and although it's very spacious, cinematographer Giora Bejach shoots it in such a way as to appear oppressively box-like. Indeed, boxes are emphasised throughout the film; the floor pattern of the Feldman living room, the container in which the soldiers at Foxtrot sleep, the dance moves of the foxtrot itself. The impression given is that the characters are fundamentally trapped - in a practical sense by the boxes with which they've surrounded themselves, and in a more metaphorical sense by the nation's psyche.

Foxtrot certainly won't be for everyone. Some will take issue with the pacing (which, it has to be said, is extremely languid), some with the allegorical nature of the story, some with the film's politics. For everyone else, however, this is a brilliantly realised family tragedy, dealing with the randomness of pain and loss in a country refusing to recognise its past. Maoz tells a personal story, but he also exposes the nature of a country whose moral crisis is no less severe than the crisis in which the Feldmans find themselves. Critiquing the practice of sending soldiers to die for absolutely nothing, as well as the xenophobic mindset that has crept into the Israeli zeitgeist, Maoz has been accused of making an "anti-Israel narrative." On the contrary, he is pleading with his country to change its ways, or it will repeat the errors of history; this is the act of a man who loves his country deeply, but who can see its flaws. In one of the most devastatingly heartbreaking lines I've heard in a long time, Dafna muses, "I remember thinking that I was going to be happy." Maoz is suggesting so too did the Israeli people.

Divided into three distinct sections, the film tells the story of Michael Feldman (a superb Lior Ashkenazi), who receives word that his son Jonathan, a conscript in the IDF, has been killed "in the line of duty". Devastated, he begins to ask questions - how was Jonathan killed, where was he stationed, is there a body - none of which are met with a straight answer. However, several hours later, Michael and his wife Dafna (Sarah Adler) are told Jonathan is still alive; a Jonathan Feldman was killed, but it was a different Jonathan Feldman. The film then jumps several days back to a forlorn desert checkpoint on Israel's northern border (codename Foxtrot) manned by a group of wet-behind-the-ears soldiers, including Jonathan Feldman (Yonatan Shiray). The most action the group see is raising the barrier to let a camel amble through and checking the IDs of the few Palestinians who pass by. Indeed, they are more interested in the fact that the shipping container in which they sleep is slowly sinking into the sand than in anything military-related. However, when a mistake whilst checking the IDs of a group of Palestinians leads to tragedy, Jonathan comes to learn just how ruthlessly political the IDF can be. Without spoiling anything, the third section, which is kind of an extended coda, then returns to Michael and Dafna's apartment, six months after the opening scenes.

In Foxtrot, Maoz constructs an allegory through which he deconstructs Israeli national myths and self-aggrandising narratives. Interrogating what he sees as a culture of denial born from a reluctance to deal with the morality and sustainability of being an occupying force, the film gets a lot of mileage out of the metaphor of the foxtrot - a dance where no matter where you go, if you follow the steps correctly, you end up back at the starting position. Applied to Israel, or indeed, any nation, Maoz is suggesting that without taking great care, countries will repeat the errors of the past, ending up exactly where they once were. The film depicts three generations of Feldmans (Michael's mother (Karin Ugowski), a Holocaust survivor now suffering from dementia, Michael himself, and Jonathan) dancing the foxtrot (literally in Michael and his mother's cases), either unwilling or unable to face up to the country's violent and traumatic past. Speaking to the Globe and Mail, Maoz explains, "Foxtrot deals with the open wound or bleeding soul of Israeli society. We dance the foxtrot; each generation tries to dance it differently but we all end up at the same starting point", whilst he tells the LA Times, "the roadblock is a microcosm of a society - any society - that has its perception distorted by a past trauma."

In a more concrete sense, in two scenes at Foxtrot, the film examines the casual sadism, unspoken racism, and braggadocious machoism that can arise from serving in the armed forces of a country perpetually at war. In the first (arguably the best scene in the film), the soldiers make a Palestinian couple stand in the pouring rain whilst their antiquated computer checks the couple's IDs. Obviously dressed for a formal night (he is in a tuxedo, she in an elegant dress), by the time the soldiers clear them to pass, their clothes are destroyed, as is her hair, and her makeup is ruined, with the soldiers even making her empty the contents of her purse onto the ground. The scene is brilliantly staged, agonisingly realistic, and takes place in real-time, with Maoz concentrating on the couple looking at one another across the roof of the car, conveying agonised helplessness, compromised innocence, understandable belligerency, and, most saliently, abject humiliation. It's a masterclass in dialogue-free storytelling, and deeply political storytelling at that. In the second scene, the soldiers act with violent impunity against a car of young Palestinians, although the act of violence itself arises from a mistake.

Aesthetically, as with Lebanon, Foxtrot is fascinatingly staged. For starters, Maoz shoots each of the three sections differently, but in ways tightly tied to their thematic focus; the first is highly restrictive, trapping us in the confined ideological headspace of the Feldmans, with the intense emotionality constantly threatening to boil over; the vast wide-open vistas of the second part contrast sharply with the confinement of the first, with the entire section threaded through with surrealism and even a hint of magic realism; the third section is darker than the others (in a literal sense), with a stark visual design that emphasises only those elements that are important to the scene. The Feldman apartment itself is extremely angular, and although it's very spacious, cinematographer Giora Bejach shoots it in such a way as to appear oppressively box-like. Indeed, boxes are emphasised throughout the film; the floor pattern of the Feldman living room, the container in which the soldiers at Foxtrot sleep, the dance moves of the foxtrot itself. The impression given is that the characters are fundamentally trapped - in a practical sense by the boxes with which they've surrounded themselves, and in a more metaphorical sense by the nation's psyche.

Foxtrot certainly won't be for everyone. Some will take issue with the pacing (which, it has to be said, is extremely languid), some with the allegorical nature of the story, some with the film's politics. For everyone else, however, this is a brilliantly realised family tragedy, dealing with the randomness of pain and loss in a country refusing to recognise its past. Maoz tells a personal story, but he also exposes the nature of a country whose moral crisis is no less severe than the crisis in which the Feldmans find themselves. Critiquing the practice of sending soldiers to die for absolutely nothing, as well as the xenophobic mindset that has crept into the Israeli zeitgeist, Maoz has been accused of making an "anti-Israel narrative." On the contrary, he is pleading with his country to change its ways, or it will repeat the errors of history; this is the act of a man who loves his country deeply, but who can see its flaws. In one of the most devastatingly heartbreaking lines I've heard in a long time, Dafna muses, "I remember thinking that I was going to be happy." Maoz is suggesting so too did the Israeli people.

Lo sapevi?

- QuizAccording to Samuel Maoz, the film was conceived as three episodes: The first sequence should shock and shake, the second should hypnotize, and the third should be moving.

- ConnessioniReferences Chi ha incastrato Roger Rabbit (1988)

- Colonne sonoreNever Been

Performed by Betzefer

I più visti

Accedi per valutare e creare un elenco di titoli salvati per ottenere consigli personalizzati

- How long is Foxtrot?Powered by Alexa

Dettagli

Botteghino

- Lordo Stati Uniti e Canada

- 618.883 USD

- Fine settimana di apertura Stati Uniti e Canada

- 31.629 USD

- 4 mar 2018

- Lordo in tutto il mondo

- 1.356.159 USD

- Tempo di esecuzione1 ora 53 minuti

- Colore

- Mix di suoni

- Proporzioni

- 2.35 : 1

Contribuisci a questa pagina

Suggerisci una modifica o aggiungi i contenuti mancanti