VALUTAZIONE IMDb

7,8/10

38.320

LA TUA VALUTAZIONE

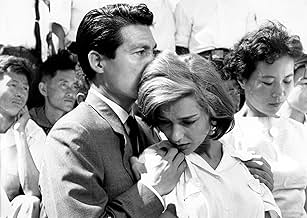

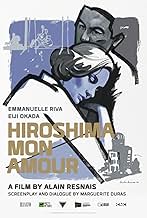

Un'attrice francese girando un film contro la guerra a Hiroshima ha una relazione con un architetto giapponese sposato mentre parlano delle loro prospettive diverse sulla guerra.Un'attrice francese girando un film contro la guerra a Hiroshima ha una relazione con un architetto giapponese sposato mentre parlano delle loro prospettive diverse sulla guerra.Un'attrice francese girando un film contro la guerra a Hiroshima ha una relazione con un architetto giapponese sposato mentre parlano delle loro prospettive diverse sulla guerra.

- Candidato a 1 Oscar

- 7 vittorie e 7 candidature totali

Emmanuelle Riva

- Elle

- (as Emmanuele Riva)

Moira Lister

- (Dubbed Emmanuelle Riva)

- (non citato nei titoli originali)

Recensioni in evidenza

I saw this thirty or so years ago. I don't remember it moving me profoundly, but then so many things at that age routinely inject you with massive change without you knowing. Seeing it now gives me great, great appreciation for what it is. And though I have been previously exposed, it washed over me all over again.

It has a laconic pace. Usually, one leverages this for relaxation into nature. Robert Redord. Here it relaxes into a tension of a different order, a quiet insistent striving for connection, like "In the Mood for Love." In this case though, the filmmaker has turned that yearning sideways so you have three dimensions of pull.

You have the desire for romance, here presented in a way that is more engaging than usual because of its folding into the other dimensions. You have the desire to comprehend war, war defined here as the sacrifice of innocents and war as a sort of incomprehensible desire running in parallel to all the other incomprehensible desires we see, every one.

And you have the desire of a film to reach into the inner world of ourselves. Film itself is a character here, with its own desires and doubts. The three of these fold in such a way that as we spend time with them we have to fill it by pouring ourselves into the film because it pulls story from us rather than serving it in timely patter.

Its an open world, made open by providing an amazing skeleton, on which we are surprised to find our own flesh and our own wondering about next actions.

He, an architect, she an actress, both highly cinematic beings. Both in Hiroshima with folded cranes over dying souls in beds. Both, this is us now, wondering, shall we do it? Shall she stay? What will it mean? Surely that the world will not be saved, not even a little, not even that they may try. Or will they? Should they?

This is such an open framework that not only do you pour yourself into it, but other filmmakers can and do. You owe it to yourself to see "H Story." after this. Or better, before. Hah!

Ted's Evaluation -- 4 of 3: Every cineliterate person should experience this.

It has a laconic pace. Usually, one leverages this for relaxation into nature. Robert Redord. Here it relaxes into a tension of a different order, a quiet insistent striving for connection, like "In the Mood for Love." In this case though, the filmmaker has turned that yearning sideways so you have three dimensions of pull.

You have the desire for romance, here presented in a way that is more engaging than usual because of its folding into the other dimensions. You have the desire to comprehend war, war defined here as the sacrifice of innocents and war as a sort of incomprehensible desire running in parallel to all the other incomprehensible desires we see, every one.

And you have the desire of a film to reach into the inner world of ourselves. Film itself is a character here, with its own desires and doubts. The three of these fold in such a way that as we spend time with them we have to fill it by pouring ourselves into the film because it pulls story from us rather than serving it in timely patter.

Its an open world, made open by providing an amazing skeleton, on which we are surprised to find our own flesh and our own wondering about next actions.

He, an architect, she an actress, both highly cinematic beings. Both in Hiroshima with folded cranes over dying souls in beds. Both, this is us now, wondering, shall we do it? Shall she stay? What will it mean? Surely that the world will not be saved, not even a little, not even that they may try. Or will they? Should they?

This is such an open framework that not only do you pour yourself into it, but other filmmakers can and do. You owe it to yourself to see "H Story." after this. Or better, before. Hah!

Ted's Evaluation -- 4 of 3: Every cineliterate person should experience this.

Memory has persistently troubled filmmakers, this facet of consciousness by which the past overwrites the present. Where do these images come from, at what behest? More importantly, by invoking memory, how can we hope to communicate to others this past experience, which only perhaps existed once?

The woman says she saw Hiroshima, the charred asphalt and scorched metal, the matted hair coming out in tufts. We may have seen the same anonymous images of disaster, elsewhere, and think we saw. We see other people like her, like ourselves as mere spectators of a film, walk around the a-bomb museum in Hiroshima among the relics of disaster, lost in thought, impotent to reconstruct the experience from these glassed remnants of it. One of the great metaphors of memory, this museum that houses and presents fragmentary what used to be and how the spectators merely move inside it—internal observers of images.

The woman says she saw Hiroshima, but we know she didn't really experience. We know by the same images we may have seen, and which we see again in the film. We know this from our own private efforts to relive time gone. We see the objects and sounds but not having walked among them, we only know them vicariously. Can we ever get to know through cinema for that matter?

The great contribution of Resnais to cinema is firstly this, the realization that this medium is inherently equipped to inherit the problem of memory—just what is this illusory space. Inherently equipped in the same breath to fail to recapture the world as it was, like memory. Where Godard would be in thirty years, Resnais—and his friend Chris Marker—already was with his debut. He gives us here a more poignant, intelligent disclaimer of the artificiality of cinema than Godard ever did. The woman is of course an actress starring in a film—about peace we find out.

But Hiroshima is not the simple ploy of a trickster, it enters beyond.

We see in Hiroshima how the past forms that make up life as we have known it, and in which the self was forged, come into play. How these things, a past love or suffering thought to matter at the time, are only small by the distance of time. That we weren't shattered by them.

And we see how, having been, these forms will vanish again. How this present love and perhaps the suffering that will follow it, thought to matter now, will also come to pass and be forgotten. How we will perhaps try to recount these events at a future time, our reconstructions faced with the same impotence to make ourselves known or know in turn.

All that remains then, having walked the city in an effort to shape again from memory, is this moment, perhaps shared by two people on a bed. These walks taken together. Perhaps a story to tell or a film about it.

Something to meditate upon.

The woman says she saw Hiroshima, the charred asphalt and scorched metal, the matted hair coming out in tufts. We may have seen the same anonymous images of disaster, elsewhere, and think we saw. We see other people like her, like ourselves as mere spectators of a film, walk around the a-bomb museum in Hiroshima among the relics of disaster, lost in thought, impotent to reconstruct the experience from these glassed remnants of it. One of the great metaphors of memory, this museum that houses and presents fragmentary what used to be and how the spectators merely move inside it—internal observers of images.

The woman says she saw Hiroshima, but we know she didn't really experience. We know by the same images we may have seen, and which we see again in the film. We know this from our own private efforts to relive time gone. We see the objects and sounds but not having walked among them, we only know them vicariously. Can we ever get to know through cinema for that matter?

The great contribution of Resnais to cinema is firstly this, the realization that this medium is inherently equipped to inherit the problem of memory—just what is this illusory space. Inherently equipped in the same breath to fail to recapture the world as it was, like memory. Where Godard would be in thirty years, Resnais—and his friend Chris Marker—already was with his debut. He gives us here a more poignant, intelligent disclaimer of the artificiality of cinema than Godard ever did. The woman is of course an actress starring in a film—about peace we find out.

But Hiroshima is not the simple ploy of a trickster, it enters beyond.

We see in Hiroshima how the past forms that make up life as we have known it, and in which the self was forged, come into play. How these things, a past love or suffering thought to matter at the time, are only small by the distance of time. That we weren't shattered by them.

And we see how, having been, these forms will vanish again. How this present love and perhaps the suffering that will follow it, thought to matter now, will also come to pass and be forgotten. How we will perhaps try to recount these events at a future time, our reconstructions faced with the same impotence to make ourselves known or know in turn.

All that remains then, having walked the city in an effort to shape again from memory, is this moment, perhaps shared by two people on a bed. These walks taken together. Perhaps a story to tell or a film about it.

Something to meditate upon.

This is surely one of the most impressive movies i know. It is also a very impressive portrait of a woman. Don't expect to see an ordinary love story -it is as not so much a love story as a story of a wounded person meeting a wounded city. A story about two people hurt by peace. Even though it is over more than four decennia old it feels surprisingly new. The reason for this must be the beautiful photography -starting with the very first shots of the two lovers- and the deliberate moving away from conventional script writing by Marguerite Dumas. The movie has the feel of an opera, with the music of Georges Delerue as a moving force. I thought it was enchanting, and it stayed with me for days after.

"Hiroshima mon amour" (1959) is an extraordinary tale of two people, a French actress and a Japanese architect - a survivor of the blast at Hiroshima. They meet in Hiroshima fifteen years after August 6, 1945 and become lovers when she came there to working on an antiwar film. They both are hunted by the memories of war and what it does to human's lives and souls. Together they live their tragic past and uncertain present in a complex series of fantasies and nightmares, flashes of memory and persistence of it. The black-and-white images by Sasha Vierney and Mikio Takhashi, especially the opening montage of bodies intertwined are unforgettable and the power of subject matter is undeniable. My only problem is the film's Oscar nominated screenplay. It works perfectly for the most of the film but then it begins to move in circles making the last 20 minutes or so go on forever.

Hiroshima Mon Amour is brilliantly made and brilliantly acted, with a thoughtful, poetic script by the great French writer, Marguerite Duras. Its images are lyrical, disturbing, fascinating, and its anti-war message is profound and still frighteningly relevant. But in terms of strict entertainment...

Any film which begins with abstracted images of the entwined body parts of human lovers, slowly becoming encrusted with ash and (presumably) atomic fallout... and then spends an obscure 15 minutes arguing about the death and disfigurement of multitudes during the atomic bomb blast in Hiroshima, and the nature of memory and forgetfulness... well, you realize immediately that this movie isn't set up to go anyplace fun. Unless your idea of "fun" is witnessing someone else's graphic misery without the cleansing catharsis that accompanies a more conventional tragedy. Hey, some people enjoy that kind of thing! Not me, but to each his/her own.

Despite a structure which is famous for meandering through time, the film's narrative is fairly cogent and non-confusing, which is a plus. But the central illicit, inter-racial affair between a French actress and the Japanese architect whom she hooks up with during a film shoot in Hiroshima... It doesn't really make any sense. From the tiny acorn of a chance hookup, grows a mad-passionate love affair based almost entirely on memories dredged from the actress' past, which she disgorges to the architect, rather like a colorless Scheherezade, as she loses all rational connection to the present, conflating a youthful indiscretion with a deceased German soldier (and her subsequent descent into madness) with the non-happenings surrounding her current Japanese amour. German, Japanese... clearly, she can't tell these Axis races apart! I understand that the point of the film was not to create strict narrative coherence, but rather to delve into some kind of symbolic and psychic clash between this cold-yet-overwrought union of a French woman and her obsessed Japanese lover, and the horrors of War. But, despite some moments which are outright absurdist in effect, the overall tone of the film is grinding in its humorlessness. As I watched the characters fatalistically surrendering to their doom, all I could think was, "man, that Marguerite Duras must have been a drag to be romantically involved with." I mean, the Duras script, for all it's poetic symbolism and intellectual brilliance, etc etc, tells a story of people who are criminally passive and hopelessly clingy. Love seems to transform her characters into mere victims, of love, of war, of life, masochistically reveling in their own operatic suffering while doing virtually nothing. As the nameless SHE recalls her own suffering during her madness, scraping her fingertips off on the saltpeter-encrusted walls of her parent's cellar-prison, then receiving validation of existence by luxuriously sucking her own blood from her ravaged hands because otherwise she is utterly alone, all I could think was... Oh brother! This character is so badly damaged, how did she ever manage to get happily married before she embarked on this chance affair in Japan? The imagery is fabulous and intense, but are these really human beings that could have plausibly embarked on a journey together? One human being, actually, because the Japanese architect is little more than a handsome cipher of "love"... love, in this story, apparently meaning the obsession that arises from the act of physical copulation, an experience which is equated with destruction of the nuclear holocaust variety. So, Marguerite Duras clearly had issues surrounding her expression and experience of sexuality. And the film betrays little in the way of empathy, either, the characters are infused with an undercurrent of intense selfishness as they struggle to connect. HE is constantly delving into HER unhappy past even though it can give neither of them any pleasure or joy. The more HE delves, the more SHE becomes hopelessly entangled, and the more obsessed HE becomes... until the cold and bitter end.

At least in an opera, you get to revel in an outpouring of passion! In this bitter pill, everything is so cold and humorless... well, it really is difficult to understand why people wax enthusiastic over this film so much. There is much here to ADMIRE... but not much to love, in my opinion. Except intellectually, because the film is awash with symbolism and thought-provoking moments. As a viewing experience for the average intellectual, such as myself, however, I felt that once was enough. The time jumping and abstractions and other critically lauded elements of this movie have been done better and more entertainingly by others. Though this is the most emotionally powerful anti-nuclear statement I've ever seen, for which, as someone who had much of his family die in the Hiroshima nuclear blast, I am profoundly grateful.

Any film which begins with abstracted images of the entwined body parts of human lovers, slowly becoming encrusted with ash and (presumably) atomic fallout... and then spends an obscure 15 minutes arguing about the death and disfigurement of multitudes during the atomic bomb blast in Hiroshima, and the nature of memory and forgetfulness... well, you realize immediately that this movie isn't set up to go anyplace fun. Unless your idea of "fun" is witnessing someone else's graphic misery without the cleansing catharsis that accompanies a more conventional tragedy. Hey, some people enjoy that kind of thing! Not me, but to each his/her own.

Despite a structure which is famous for meandering through time, the film's narrative is fairly cogent and non-confusing, which is a plus. But the central illicit, inter-racial affair between a French actress and the Japanese architect whom she hooks up with during a film shoot in Hiroshima... It doesn't really make any sense. From the tiny acorn of a chance hookup, grows a mad-passionate love affair based almost entirely on memories dredged from the actress' past, which she disgorges to the architect, rather like a colorless Scheherezade, as she loses all rational connection to the present, conflating a youthful indiscretion with a deceased German soldier (and her subsequent descent into madness) with the non-happenings surrounding her current Japanese amour. German, Japanese... clearly, she can't tell these Axis races apart! I understand that the point of the film was not to create strict narrative coherence, but rather to delve into some kind of symbolic and psychic clash between this cold-yet-overwrought union of a French woman and her obsessed Japanese lover, and the horrors of War. But, despite some moments which are outright absurdist in effect, the overall tone of the film is grinding in its humorlessness. As I watched the characters fatalistically surrendering to their doom, all I could think was, "man, that Marguerite Duras must have been a drag to be romantically involved with." I mean, the Duras script, for all it's poetic symbolism and intellectual brilliance, etc etc, tells a story of people who are criminally passive and hopelessly clingy. Love seems to transform her characters into mere victims, of love, of war, of life, masochistically reveling in their own operatic suffering while doing virtually nothing. As the nameless SHE recalls her own suffering during her madness, scraping her fingertips off on the saltpeter-encrusted walls of her parent's cellar-prison, then receiving validation of existence by luxuriously sucking her own blood from her ravaged hands because otherwise she is utterly alone, all I could think was... Oh brother! This character is so badly damaged, how did she ever manage to get happily married before she embarked on this chance affair in Japan? The imagery is fabulous and intense, but are these really human beings that could have plausibly embarked on a journey together? One human being, actually, because the Japanese architect is little more than a handsome cipher of "love"... love, in this story, apparently meaning the obsession that arises from the act of physical copulation, an experience which is equated with destruction of the nuclear holocaust variety. So, Marguerite Duras clearly had issues surrounding her expression and experience of sexuality. And the film betrays little in the way of empathy, either, the characters are infused with an undercurrent of intense selfishness as they struggle to connect. HE is constantly delving into HER unhappy past even though it can give neither of them any pleasure or joy. The more HE delves, the more SHE becomes hopelessly entangled, and the more obsessed HE becomes... until the cold and bitter end.

At least in an opera, you get to revel in an outpouring of passion! In this bitter pill, everything is so cold and humorless... well, it really is difficult to understand why people wax enthusiastic over this film so much. There is much here to ADMIRE... but not much to love, in my opinion. Except intellectually, because the film is awash with symbolism and thought-provoking moments. As a viewing experience for the average intellectual, such as myself, however, I felt that once was enough. The time jumping and abstractions and other critically lauded elements of this movie have been done better and more entertainingly by others. Though this is the most emotionally powerful anti-nuclear statement I've ever seen, for which, as someone who had much of his family die in the Hiroshima nuclear blast, I am profoundly grateful.

Lo sapevi?

- QuizThis film pioneered the use of jump cutting to and from a flashback, and of very brief flashbacks to suggest obtrusive memories.

- BlooperWhen Elle leaves the hotel to go the set, she is wearing a nurse's uniform with a headscarf and carrying a black handbag. When Lui meets her on the set, she is now wearing a skirt and blouse and still has the headscarf. When they leave the set, the headscarf is left behind. When they get to Lui's house, she now has a white jacket.

- ConnessioniEdited into Histoire(s) du cinéma: Le contrôle de l'univers (1999)

I più visti

Accedi per valutare e creare un elenco di titoli salvati per ottenere consigli personalizzati

- How long is Hiroshima Mon Amour?Powered by Alexa

Dettagli

- Data di uscita

- Paesi di origine

- Lingue

- Celebre anche come

- Hiroshima Mon Amour

- Luoghi delle riprese

- Nevers, Nièvre, Francia(street scenes, river banks)

- Aziende produttrici

- Vedi altri crediti dell’azienda su IMDbPro

Botteghino

- Lordo Stati Uniti e Canada

- 96.439 USD

- Fine settimana di apertura Stati Uniti e Canada

- 18.494 USD

- 19 ott 2014

- Lordo in tutto il mondo

- 139.947 USD

- Tempo di esecuzione

- 1h 30min(90 min)

- Colore

- Mix di suoni

- Proporzioni

- 1.37 : 1

Contribuisci a questa pagina

Suggerisci una modifica o aggiungi i contenuti mancanti