AVALIAÇÃO DA IMDb

7,6/10

1,8 mil

SUA AVALIAÇÃO

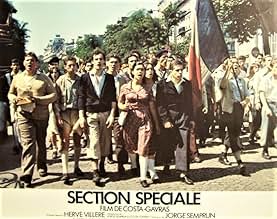

Na França ocupada durante a Segunda Guerra Mundial, um oficial alemão é assassinado. O governo colaboracionista de Vichy decide responsabilizar seis pequenos criminosos. Juízes leais são cha... Ler tudoNa França ocupada durante a Segunda Guerra Mundial, um oficial alemão é assassinado. O governo colaboracionista de Vichy decide responsabilizar seis pequenos criminosos. Juízes leais são chamados para condená-los o mais rápido possível.Na França ocupada durante a Segunda Guerra Mundial, um oficial alemão é assassinado. O governo colaboracionista de Vichy decide responsabilizar seis pequenos criminosos. Juízes leais são chamados para condená-los o mais rápido possível.

- Direção

- Roteiristas

- Artistas

- Prêmios

- 2 vitórias e 2 indicações no total

Michael Lonsdale

- Pierre Pucheu, le ministre de l'Intérieur

- (as Michel Lonsdale)

- Direção

- Roteiristas

- Elenco e equipe completos

- Produção, bilheteria e muito mais no IMDbPro

Avaliações em destaque

After the film of Max OPHULS "le chagrin et la pitié" this picture shows the obedience of 99% of the judjes in France during the german occupation. Of course all the jews or any reluctant were killed. It's a shame for my country. As said Otto ABETZ, chief of the Gestapo in France, "the french used to make too much"! For us it's not a congratulation. The actal Président Jacques CHIRAC took heart to empasize this on 1995.

What makes this film particularly unsettling - and ultimately, cinematically arresting - is the way it burrows into the machinery of collaboration with a kind of icy, procedural detachment that mimics the moral coldness of its subjects. Shot in 1975, in a France still reckoning with the complexities of its wartime past, the movie avoids the heroics and melancholic resistance tropes common in earlier French productions like Le Père Tranquille (1946) or even the more somber Army of Shadows (L'Armée des Ombres, 1969). Instead, it aligns more squarely - and deliberately - with the post-1968 generation of politically urgent cinema that sought to expose not the glories, but the compromises, hypocrisies, and complicities of occupied France.

This film is part of the lineage that includes The Sorrow and the Pity (Le Chagrin et la Pitié, 1969) and Lacombe Lucien (1974), but it differs in focus. Where those films examine attitudes, behaviors, and emotional states under occupation, this one dissects institutional collaboration - specifically the judicial system's transformation into an obedient executor of Nazi demands. Stylistically, it is more clinical than its predecessors. It avoids the sentimentality or psychological drama that Lacombe Lucien allowed to seep in, opting instead for a calculated, almost Kubrickian austerity that keeps the audience at a remove. There is no overt emotional manipulation in the mise-en-scène; no swelling music or pointed visual cues to tell us how to feel. The horror lies in the banality, and the camera knows it. Static frames dominate, mirroring the rigidity of judicial decorum and the paralysis of ethics.

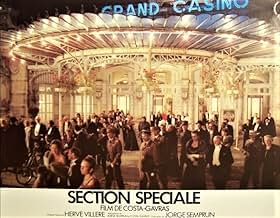

Visually, the film is meticulous, often using architectural symmetry and stark lighting to emphasize the mechanized, depersonalized operations of the court. Interiors - all paneling, polished brass, and dim lamplight - are rendered with an oppressive stillness that communicates the suffocating morality vacuum in which these officials function. The costuming is likewise precise, capturing the somber formality of Vichy France's legal elite, all robes and ritual, masking the rot beneath.

The performances follow suit. This is not a film driven by actorly bravura, but by a measured, near-sociological approach to character. The cast moves with a quiet dread, underplaying rather than emoting, which lends the entire enterprise an eerie plausibility. No one plays a villain in the conventional sense - which is precisely the point. The most chilling figures are those who appear to believe, or convincingly pretend to believe, in the legitimacy of their duties. One notable exception is a senior judge whose restrained performance betrays just the slightest quiver of conscience - never voiced, only momentarily glimpsed in a faltering hand or an elongated pause - suggesting the silent tension between professional decorum and moral corrosion.

Contextually, 1975 France was grappling with a period of deep self-examination. The Gaullist myth of widespread resistance had begun to erode in public discourse, partly due to the political climate of the 1970s - student protests, Vietnam, and postcolonial anxieties - which had reoriented cultural attention toward systemic critique. This film reflects that shift. It isn't merely about collaboration; it is about how systems, supposedly designed for justice, can be turned inside out to serve tyranny - and how those who operate within them justify their obedience. The movie's attention to legal ritual - the precise language, the ceremonial dress, the self-serious procedures - makes clear how collaboration is not always enacted with guns and salutes, but with signatures and sentence reductions.

Technically, the film's sound design stands out for its restraint. There is minimal non-diegetic music, and what little exists serves to punctuate rather than embellish. Silence - or the muffled ambiance of closed-door meetings - becomes a weapon, reinforcing the isolation of those who are about to be sacrificed on the altar of political expediency. The pacing may frustrate some viewers accustomed to more dynamic storytelling, but its slowness is deliberate, mirroring the gradual, grinding momentum of bureaucratic injustice. This is a machine at work, and the viewer is not meant to be entertained so much as implicated.

If there's a point of comparison that reveals the specific achievement of this film, it might be The Assassination of Matteotti (Il delitto Matteotti, 1973), which similarly explores how fascist ideology seeps into the procedural and institutional fabric of a society. Both films share a preoccupation with how "normal" men of the state become facilitators of repression, not through fanatical violence, but through a perversion of legality. However, where Il delitto Matteotti leans more into overt political drama and historical speech, this film prefers ambiguity and understatement, assuming the viewer can read between the silences and ceremonial lines.

Another worthwhile comparison might be with The Trial Begins (El proceso empieza, 1960s, Spain), a lesser-known Spanish film centered around the Francoist courts. Like the movie in question, it emphasizes legal choreography as a mechanism of state violence, though it lacks the formal rigor and detached poetics seen here. Still, both films gesture toward a shared concern with how authoritarian systems inscribe their violence through the law, making injustice seem inevitable - even rational.

The cinematography makes subtle use of framing to reinforce the ideological claustrophobia. High-angle shots that look down on characters during pivotal decisions emphasize their lack of autonomy, while low-angle perspectives used sparingly hint at the grotesque self-importance with which some of the judges carry out their duties. The lighting, never expressive, becomes more shadowed as the story progresses, creating a visual metaphor for the moral descent taking place behind the scenes.

There is also a disturbing irony at play throughout, never overstated, but made palpable through editing choices that linger just long enough to make the viewer uncomfortable. Reaction shots from bureaucrats during key moments - usually cut just a beat too late - betray the slight satisfaction, the quiet dread, or the total indifference that these men feel as they enact policies under the guise of national interest. These micro-expressions become testimonies more damning than any written decree.

What this film accomplishes - and few others do with such quiet venom - is to show how evil can drape itself in tradition, legalism, and the rhetoric of stability. Its targets are not monsters but administrators. And in choosing to observe rather than dramatize, the film refuses the comfort of moral distance. We watch, impotent, as the machinery grinds forward. The film doesn't accuse directly; it simply invites us to look - and then dares us to look away.

That said, for all its conceptual rigor and political force, this is not a film without cinematic limitations. The direction embraces an austerity that, while coherent with the film's dry, accusatory tone, exposes certain shortcomings when viewed through a more formal lens. Costume and makeup design are serviceable but lack texture or historical depth. There is little visual richness to immerse the viewer in the era - a deliberate rejection, perhaps, of period-piece aestheticism, but one that occasionally flattens the screen rather than sharpening it.

Similarly, the dialogue, while precise in its argumentative function, sometimes lapses into repetition or stiffness. Characters serve the thesis rather than embodying emotional or psychological nuance. This discursive mode, though effective in sustaining the film's political clarity, can weigh down the dramatic vitality. The narrative moves at a deliberate, at times sluggish pace, and the repetition of judicial procedures - realistic as it may be - borders on the mechanical.

These choices, arguably necessary to preserve the film's ideological clarity, come at a cost to its cinematic fullness. Judged strictly on formal terms, a more restrained rating - something closer to 7 out of 10 - would be reasonable. But insofar as one values its historical precision, thematic courage, and unique position within the cinema of Nazi occupation and institutional collaboration, the higher score - 9 out of 10 - stands not as a marker of aesthetic perfection, but of intellectual and political urgency.

This film is part of the lineage that includes The Sorrow and the Pity (Le Chagrin et la Pitié, 1969) and Lacombe Lucien (1974), but it differs in focus. Where those films examine attitudes, behaviors, and emotional states under occupation, this one dissects institutional collaboration - specifically the judicial system's transformation into an obedient executor of Nazi demands. Stylistically, it is more clinical than its predecessors. It avoids the sentimentality or psychological drama that Lacombe Lucien allowed to seep in, opting instead for a calculated, almost Kubrickian austerity that keeps the audience at a remove. There is no overt emotional manipulation in the mise-en-scène; no swelling music or pointed visual cues to tell us how to feel. The horror lies in the banality, and the camera knows it. Static frames dominate, mirroring the rigidity of judicial decorum and the paralysis of ethics.

Visually, the film is meticulous, often using architectural symmetry and stark lighting to emphasize the mechanized, depersonalized operations of the court. Interiors - all paneling, polished brass, and dim lamplight - are rendered with an oppressive stillness that communicates the suffocating morality vacuum in which these officials function. The costuming is likewise precise, capturing the somber formality of Vichy France's legal elite, all robes and ritual, masking the rot beneath.

The performances follow suit. This is not a film driven by actorly bravura, but by a measured, near-sociological approach to character. The cast moves with a quiet dread, underplaying rather than emoting, which lends the entire enterprise an eerie plausibility. No one plays a villain in the conventional sense - which is precisely the point. The most chilling figures are those who appear to believe, or convincingly pretend to believe, in the legitimacy of their duties. One notable exception is a senior judge whose restrained performance betrays just the slightest quiver of conscience - never voiced, only momentarily glimpsed in a faltering hand or an elongated pause - suggesting the silent tension between professional decorum and moral corrosion.

Contextually, 1975 France was grappling with a period of deep self-examination. The Gaullist myth of widespread resistance had begun to erode in public discourse, partly due to the political climate of the 1970s - student protests, Vietnam, and postcolonial anxieties - which had reoriented cultural attention toward systemic critique. This film reflects that shift. It isn't merely about collaboration; it is about how systems, supposedly designed for justice, can be turned inside out to serve tyranny - and how those who operate within them justify their obedience. The movie's attention to legal ritual - the precise language, the ceremonial dress, the self-serious procedures - makes clear how collaboration is not always enacted with guns and salutes, but with signatures and sentence reductions.

Technically, the film's sound design stands out for its restraint. There is minimal non-diegetic music, and what little exists serves to punctuate rather than embellish. Silence - or the muffled ambiance of closed-door meetings - becomes a weapon, reinforcing the isolation of those who are about to be sacrificed on the altar of political expediency. The pacing may frustrate some viewers accustomed to more dynamic storytelling, but its slowness is deliberate, mirroring the gradual, grinding momentum of bureaucratic injustice. This is a machine at work, and the viewer is not meant to be entertained so much as implicated.

If there's a point of comparison that reveals the specific achievement of this film, it might be The Assassination of Matteotti (Il delitto Matteotti, 1973), which similarly explores how fascist ideology seeps into the procedural and institutional fabric of a society. Both films share a preoccupation with how "normal" men of the state become facilitators of repression, not through fanatical violence, but through a perversion of legality. However, where Il delitto Matteotti leans more into overt political drama and historical speech, this film prefers ambiguity and understatement, assuming the viewer can read between the silences and ceremonial lines.

Another worthwhile comparison might be with The Trial Begins (El proceso empieza, 1960s, Spain), a lesser-known Spanish film centered around the Francoist courts. Like the movie in question, it emphasizes legal choreography as a mechanism of state violence, though it lacks the formal rigor and detached poetics seen here. Still, both films gesture toward a shared concern with how authoritarian systems inscribe their violence through the law, making injustice seem inevitable - even rational.

The cinematography makes subtle use of framing to reinforce the ideological claustrophobia. High-angle shots that look down on characters during pivotal decisions emphasize their lack of autonomy, while low-angle perspectives used sparingly hint at the grotesque self-importance with which some of the judges carry out their duties. The lighting, never expressive, becomes more shadowed as the story progresses, creating a visual metaphor for the moral descent taking place behind the scenes.

There is also a disturbing irony at play throughout, never overstated, but made palpable through editing choices that linger just long enough to make the viewer uncomfortable. Reaction shots from bureaucrats during key moments - usually cut just a beat too late - betray the slight satisfaction, the quiet dread, or the total indifference that these men feel as they enact policies under the guise of national interest. These micro-expressions become testimonies more damning than any written decree.

What this film accomplishes - and few others do with such quiet venom - is to show how evil can drape itself in tradition, legalism, and the rhetoric of stability. Its targets are not monsters but administrators. And in choosing to observe rather than dramatize, the film refuses the comfort of moral distance. We watch, impotent, as the machinery grinds forward. The film doesn't accuse directly; it simply invites us to look - and then dares us to look away.

That said, for all its conceptual rigor and political force, this is not a film without cinematic limitations. The direction embraces an austerity that, while coherent with the film's dry, accusatory tone, exposes certain shortcomings when viewed through a more formal lens. Costume and makeup design are serviceable but lack texture or historical depth. There is little visual richness to immerse the viewer in the era - a deliberate rejection, perhaps, of period-piece aestheticism, but one that occasionally flattens the screen rather than sharpening it.

Similarly, the dialogue, while precise in its argumentative function, sometimes lapses into repetition or stiffness. Characters serve the thesis rather than embodying emotional or psychological nuance. This discursive mode, though effective in sustaining the film's political clarity, can weigh down the dramatic vitality. The narrative moves at a deliberate, at times sluggish pace, and the repetition of judicial procedures - realistic as it may be - borders on the mechanical.

These choices, arguably necessary to preserve the film's ideological clarity, come at a cost to its cinematic fullness. Judged strictly on formal terms, a more restrained rating - something closer to 7 out of 10 - would be reasonable. But insofar as one values its historical precision, thematic courage, and unique position within the cinema of Nazi occupation and institutional collaboration, the higher score - 9 out of 10 - stands not as a marker of aesthetic perfection, but of intellectual and political urgency.

10LucasHC_

I say it is interesting because it shows how the law is not a science immune to abuse and ideologies, used to commit injustices.

After the advent of the French Revolution, and many subsequent events, legal science and contractual relations became the great tenets of modern society, but the powerful of this Earth always found a way to pervert things, and with the science of law it was not different.

From the point of view of legal principles it's painful, but what relieves conscience are the negatives of the great jurists, leaving only a few pessimists who thought that Nazi Germany would be the new world order after the Second War. They went bad, they got dirty in the story.

We must never give in to evil, even if it imposes itself as a new and "saving" order of the motherland.

After the advent of the French Revolution, and many subsequent events, legal science and contractual relations became the great tenets of modern society, but the powerful of this Earth always found a way to pervert things, and with the science of law it was not different.

From the point of view of legal principles it's painful, but what relieves conscience are the negatives of the great jurists, leaving only a few pessimists who thought that Nazi Germany would be the new world order after the Second War. They went bad, they got dirty in the story.

We must never give in to evil, even if it imposes itself as a new and "saving" order of the motherland.

Costa-Gavras was an activist director concerning political cinema, this turn the target is the infamous Section Speciale hastily assembled in occupied France on WWII by Nazi forces since 1940, such military occupation certainly will trigger the patriotic sense on the French soon or later, in response at first attempt against a German Officer they offer to Germans a quick solution, engendering a Section Speciale grounded in a retroactive law enforced overnight.

As expect many magistrates turn down the crying shame ruling, then they have carefully pick up the greediest judges for the power passing over legal principles aiming for earnings by promotion on high-ranking of French justice, worst they have to overturn the district attorney's office and all lawyers as well to condemn to death everyone less fortunate by a light offence.

Thanks for reading.

Resume:

First watch: 2024 / How many: 1 / Source: DVD / Rating: 8.

As expect many magistrates turn down the crying shame ruling, then they have carefully pick up the greediest judges for the power passing over legal principles aiming for earnings by promotion on high-ranking of French justice, worst they have to overturn the district attorney's office and all lawyers as well to condemn to death everyone less fortunate by a light offence.

Thanks for reading.

Resume:

First watch: 2024 / How many: 1 / Source: DVD / Rating: 8.

Unlike "Z" and "L'Aveu" ,"Section Speciale" was not a big success when it was theatrically released ."Z" took place in Greece and "L"Aveu" behind the iron curtain."Section Spéciale" takes place in France and it is no easy to clean your own backyard .Coming after "Le Chagrin Et La Pitié" and "Lacombe Lucien" which both showed the other side of the French attitude towards their occupying forces (till the seventies,most of the movies dealt with the French resistance from "Le Père Tranquille" to "L'Armée Des Ombres" ),Costa-Gavras showed how the French used the law to commit injustice .And these French who sentenced their compatriots to death were not troubled after the Liberation (whereas others who did not kill anybody were).Main objection:"if we had not sacrificed these ones,a hundred of French people would have been shot..."

Although Costa-Gavras made his movie accessible to everyone (story telling has always been his forte,even in his American career),he did not try to sweeten the screenplay with love affairs or melodrama (the past of one of the victims,played by Yves Robert ,is almost treated with nonchalance and casualness).Although there is no superstar here (nobody like Yves Montand) most of the actors,even in small parts,were widely known by the French audience of the seventies: his producer,Jacques Perrin,had been the rebellious journalist in "Z" and he portrays the only lawyer who really "plays".

But Costa-Gavras's best idea for the casting is the choice of Claude Pieplu as the presiding judge: his high-pitched voice -it's necessary to see the movie in French with subtitles- works wonders,so to speak,and I can't see no other French actor in this part.This man was so talented he would convince you that all he did was for the sake of his homeland.

Although Costa-Gavras made his movie accessible to everyone (story telling has always been his forte,even in his American career),he did not try to sweeten the screenplay with love affairs or melodrama (the past of one of the victims,played by Yves Robert ,is almost treated with nonchalance and casualness).Although there is no superstar here (nobody like Yves Montand) most of the actors,even in small parts,were widely known by the French audience of the seventies: his producer,Jacques Perrin,had been the rebellious journalist in "Z" and he portrays the only lawyer who really "plays".

But Costa-Gavras's best idea for the casting is the choice of Claude Pieplu as the presiding judge: his high-pitched voice -it's necessary to see the movie in French with subtitles- works wonders,so to speak,and I can't see no other French actor in this part.This man was so talented he would convince you that all he did was for the sake of his homeland.

Você sabia?

- CuriosidadesAll the names of the accused are real. Abraham Trzebrucki, André Bréchet, Émile Bastard, Lucien Sampaix, etc.

- Erros de gravaçãoWhen two of the judges have lunch on a restaurant patio, two members of the French Milice, wearing the gamma insignia, are sitting at a table behind. The action is set in summer 1941 but the Milice, subordinated to the French government in Vichy was created in January 1943.

- ConexõesReferenced in Roma Armada (1976)

Principais escolhas

Faça login para avaliar e ver a lista de recomendações personalizadas

- How long is Special Section?Fornecido pela Alexa

Detalhes

- Tempo de duração1 hora 58 minutos

- Mixagem de som

- Proporção

- 1.66 : 1

Contribua para esta página

Sugerir uma alteração ou adicionar conteúdo ausente

Principal brecha

By what name was Sessão Especial de Justiça (1975) officially released in India in English?

Responda