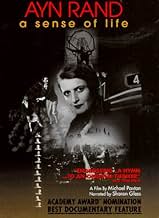

Adicionar um enredo no seu idiomaA documentary focusing on the life of novelist and philosopher Ayn Rand, the author of the bestselling novels The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged and originator of the Objectivist philosophy... Ler tudoA documentary focusing on the life of novelist and philosopher Ayn Rand, the author of the bestselling novels The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged and originator of the Objectivist philosophy.A documentary focusing on the life of novelist and philosopher Ayn Rand, the author of the bestselling novels The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged and originator of the Objectivist philosophy.

- Direção

- Roteirista

- Artistas

- Indicado a 1 Oscar

- 1 vitória e 2 indicações no total

Sharon Gless

- Narrator

- (narração)

Michael S. Berliner

- Self - Editor of Rand's Letters

- (as Dr. Michael S. Berliner)

Harry Binswanger

- Self - Professor and Friend

- (as Dr. Harry Binswanger)

Leonard Peikoff

- Self - Intellectual Heir and Friend

- (as Dr. Leonard Peikoff)

John Ridpath

- Self - Professor: York University

- (as Dr. John Ridpath)

Buzz Aldrin

- Self - Astronaut on Moon

- (cenas de arquivo)

- (não creditado)

Neil Armstrong

- Self - Astronaut on Moon

- (cenas de arquivo)

- (não creditado)

Cecil B. DeMille

- Self - Addresses Extras

- (cenas de arquivo)

- (não creditado)

Phil Donahue

- Self - Interviews Ayn Rand

- (cenas de arquivo)

- (não creditado)

Grand Duke Nicholas

- Self - Accompanies Tsar Nicholas

- (cenas de arquivo)

- (não creditado)

Edith Head

- Self - Pins Costume

- (cenas de arquivo)

- (não creditado)

Avaliações em destaque

Ayn Rand created herself out of whole cloth. This must be acknowledged, and yes it's impressive. Often an immigrant, who had to struggle for freedom, ends up doing more than a rank and file American, who takes it for granted. Rand was definitely a force to be reckoned with. Unfortunately... paradoxically... over-achievers can also be full of cr*p. Any admiration for Rand must be tempered by the fact that her writing is a mono-maniacal, unpersuasive snooze. Add to that the sheer creepy, oiliness of the also-Rands she left behind, and she's a complete wash-out. No college studies Rand's disreputable "philosophy."

Rand didn't have a body of work that became a school; instead she had a lot of hard-won, reactive opinions that became serviceable as a personal philosophy; and a generous segment of the population without rudders came to grovel at her feet, and hear why being selfish was actually a good thing; uniting sociopaths and young capitalists under one umbrella.

She quickly became a self-parody. She hated collectives terribly but paradoxically could only conceive of individualism as a cultish dogma she constrained you with. (!?) As few in America have a philosophical life, an early naive encounter with her material (as with $cientology, and Moonie literature) is apt to derail the development of actual emotional depth or a conscience for five to thirty years, lost in the fog of mystification and hero worship.

Her work follows an absurd tiresome pattern. You could write the next Rand tome by just following this handy template: A vigorously independent industrialist wants to use (insert some industry) to prove he's got big brass ones. For 1,500 pages he must endure a bizarre gang of paper-deep anti-individualists motivated by volition that no one has ever actually encountered on earth (Bad man: "grrrrr... I hate maverick individuals!" Good man: "I hate collectives!"). But with the attention of an impressively miserable woman, who only experiences joy when (pick two: she breaks beautiful things / gets put in her place sexually / she can pursue her erotic fixation with machinery) they stand together in triumph on top of (pick one: his own skyscraper, his train, some other phallic symbol) in the end. Spare yourself a read of Atlas Shrugged and just wait for Brad Pitt/Angelina Jolie's self-impressed, half-understood production which should be putting theater-goers to sleep in the next year or so.

The ultimate refutation of her ideas comes from Allen Greenspan, a Rand acolyte who when asked to explain why he allowed the country's economy to run itself into the ground, stated that he couldn't fathom that bankers would act in their own self-interest without concern for the well-being of the nation. Well, I guess that makes me smarter than you Allen. Please go away, Randlings.

Rand didn't have a body of work that became a school; instead she had a lot of hard-won, reactive opinions that became serviceable as a personal philosophy; and a generous segment of the population without rudders came to grovel at her feet, and hear why being selfish was actually a good thing; uniting sociopaths and young capitalists under one umbrella.

She quickly became a self-parody. She hated collectives terribly but paradoxically could only conceive of individualism as a cultish dogma she constrained you with. (!?) As few in America have a philosophical life, an early naive encounter with her material (as with $cientology, and Moonie literature) is apt to derail the development of actual emotional depth or a conscience for five to thirty years, lost in the fog of mystification and hero worship.

Her work follows an absurd tiresome pattern. You could write the next Rand tome by just following this handy template: A vigorously independent industrialist wants to use (insert some industry) to prove he's got big brass ones. For 1,500 pages he must endure a bizarre gang of paper-deep anti-individualists motivated by volition that no one has ever actually encountered on earth (Bad man: "grrrrr... I hate maverick individuals!" Good man: "I hate collectives!"). But with the attention of an impressively miserable woman, who only experiences joy when (pick two: she breaks beautiful things / gets put in her place sexually / she can pursue her erotic fixation with machinery) they stand together in triumph on top of (pick one: his own skyscraper, his train, some other phallic symbol) in the end. Spare yourself a read of Atlas Shrugged and just wait for Brad Pitt/Angelina Jolie's self-impressed, half-understood production which should be putting theater-goers to sleep in the next year or so.

The ultimate refutation of her ideas comes from Allen Greenspan, a Rand acolyte who when asked to explain why he allowed the country's economy to run itself into the ground, stated that he couldn't fathom that bankers would act in their own self-interest without concern for the well-being of the nation. Well, I guess that makes me smarter than you Allen. Please go away, Randlings.

What a horrible woman. I have never read anything by her or about her but was really astounded by this documentary. Basically, she believes that everyone should be selfish and think only of themselves. Government should not take care of anyone. There is no God. she babbles incoherently about the future of the human race and her greatest philosophical achievement is a book about an architect that every selfish conservative in the world has bought next to only the bible. She sounds like a cult. I plan to watch Fountainhead. I wonder how it became the favorite book of Anne Hathoway (The Princess Diary). Wonder what her parents were like? If I somehow come up with a different opinion, I will let you know. Until then, watch this and tell me if you can find any redeeming value. Check out the parts where the audience is watching her on talk shows of the 70's with a collective look of horror as she spouts out her ideas that God doesn't exist, people should not seek help from their government and people who believe in helping others are wimps. Now you will know why conservatives love her and shun Jesus, Gandhi, Martin Luther King and other petty altruists. Ugh....

Ayn Rand has helped me to have an integrated view of life.

She teaches for reason and trade, instead of faith and force.

She is against mysticism, which rules by means of guilt, by keeping men convinced of their insignificance on earth. She is against the dogma of man's poverty and misery on earth.

She teaches you to face the universe, free to declare your mind is competent to deal with all the problems of existence and that reason is the only means of knowledge.

Ayn Rand states that intellect is a practical faculty, a guide to man's successful existence on earth, and that its task is the study of reality (as well as the production of wealth), not contemplation of unintelligible feelings nor a special monopoly on the "unknowable".

She is for that productive person who is confident of his ability to earn his living - who takes pride in his work and in the value of his product - who drives himself with inexhaustible energy and limitless ambition to do better and still better and even better - who is willing to bear penalties for his mistakes and expects rewards for his achievements - who looks at the universe with the fearless eagerness of a child, knowing it to be intelligible - who demands straight lines, clear terms, precise definitions - who stands in full sun light and has no use for the murky fog of the hidden, the secret, the unnamed, or for any code from psycho-epistemology of guilt.

Her words will help people to free themselves from fear and force forever.

Thanks Ayn for you direction. She has given me an integrated view of life. I hope, by reading her books, you get it too.

She teaches for reason and trade, instead of faith and force.

She is against mysticism, which rules by means of guilt, by keeping men convinced of their insignificance on earth. She is against the dogma of man's poverty and misery on earth.

She teaches you to face the universe, free to declare your mind is competent to deal with all the problems of existence and that reason is the only means of knowledge.

Ayn Rand states that intellect is a practical faculty, a guide to man's successful existence on earth, and that its task is the study of reality (as well as the production of wealth), not contemplation of unintelligible feelings nor a special monopoly on the "unknowable".

She is for that productive person who is confident of his ability to earn his living - who takes pride in his work and in the value of his product - who drives himself with inexhaustible energy and limitless ambition to do better and still better and even better - who is willing to bear penalties for his mistakes and expects rewards for his achievements - who looks at the universe with the fearless eagerness of a child, knowing it to be intelligible - who demands straight lines, clear terms, precise definitions - who stands in full sun light and has no use for the murky fog of the hidden, the secret, the unnamed, or for any code from psycho-epistemology of guilt.

Her words will help people to free themselves from fear and force forever.

Thanks Ayn for you direction. She has given me an integrated view of life. I hope, by reading her books, you get it too.

As someone who spent a lot of time reading and thinking about Rand's ideas many years ago, I found this film very informative and entertaining. It presents Rand with just the right breath of grandeur. It shows her the way I like to think of her.

Like Thomas Jefferson, flaws in Rand's personal life throw a bit of shadow on her intellectual triumphs. This is not to suggest that Rand's achievements come close to Jefferson's. But, like Rand, his lifestyle contradicted his life's major achievement: the Author of The Declaration of Independence was a slaveholder.

In Rand's case, the champion of individualism surrounded herself with a "Collective" of yes-men (and -women) that systematically excluded anyone who didn't toe the line on matters of philosophy, religion, aesthetics, and even cigarette smoking. Incredibly, this champion of "independent judgement based on facts" would actually forbid her followers from reading things written by people she deemed "evil."

But, just as a tribute to Jefferson might not dwell on slavery at Monticello or mention Sally Hemmings, this love letter to Ayn doesn't explore her problematic social life or her peculiar band of followers. But I still think this documentary earned its accolades from the film industry. Ayn Rand probably would have approved of the film herself.

Like Thomas Jefferson, flaws in Rand's personal life throw a bit of shadow on her intellectual triumphs. This is not to suggest that Rand's achievements come close to Jefferson's. But, like Rand, his lifestyle contradicted his life's major achievement: the Author of The Declaration of Independence was a slaveholder.

In Rand's case, the champion of individualism surrounded herself with a "Collective" of yes-men (and -women) that systematically excluded anyone who didn't toe the line on matters of philosophy, religion, aesthetics, and even cigarette smoking. Incredibly, this champion of "independent judgement based on facts" would actually forbid her followers from reading things written by people she deemed "evil."

But, just as a tribute to Jefferson might not dwell on slavery at Monticello or mention Sally Hemmings, this love letter to Ayn doesn't explore her problematic social life or her peculiar band of followers. But I still think this documentary earned its accolades from the film industry. Ayn Rand probably would have approved of the film herself.

The memorable, and ultimately appalling, thing about Ayn Rand: A Sense of Life,the new film biography of the right-wing novelist-philosopher, is that it is perfectly true to its subject. Just as Rand, who was born in 1905 in Leningrad as it was convulsed by revolution, declared that she had not changed her ideas about anything since the age of 2½, this reverential documentary presents her thoughts as uncontested truth.

The evangelical tone is set by filmmaker Michael Paxton, quoted in the press material as saying that he first found Ayn Rand when he was an adolescent trying "to find a book that would answer all of my questions and give my life meaning." A Sense of Life contents itself with interviewing her friends and acolytes. It acknowledges that she was much criticized, and even considered a crank, but her critics don't appear on screen and their views are not explained.

But neither Rand nor the film should be dismissed, if only because she is widely read and her ideas have been deeply influential. They lie behind much neo-conservative commentary, which recasts democracy -- essentially an untidy contest of ideas and interests -- as a secular religion (she called it Objectivism) where competing points of view are greeted with adolescent impatience.

But more particularly, Rand's influence helps explain the concealed romanticism of much right-wing commentary, which replaces iconic figures from other belief systems with buccaneering businessmen and entrepreneurs. As this film unwittingly makes clear, Rand herself was one of the great romantics. A worshipper of Hollywood, and partly successful screenwriter, she laments that the film version of her novel The Fountainhead "lacked the Romanticism of the German films she had loved as a youth." That these films were the precursors of fascism seems to have escaped the notice of Rand and her disciples.

This appealing simplicity, a charming oblivion to her own contradictions, gave Rand a widespread following among those looking for answers, even as it exasperated intellectuals. She believed that each individual has a sacred core of personal talents and dreams which can be expressed in a free society. People may choose to co-operate, but these choices must ultimately serve their self-interest. If an action is truly selfless, she often said, it is "evil." Her reasoning was that selflessness in one's own life can be enlisted by political systems such as communism that call on human beings to sacrifice themselves for the state.

These views were apparently burned into Rand's consciousness by the horrors she witnessed during and after the Russian Revolution -- a period the film recalls through family photographs and archival film footage. She decided that capitalism was the only hope for mankind. "Capitalism leaves every man free to choose the work he likes," she declares on screen, oblivious to the deadening monotony of most people's jobs, not to mention unemployment.

Like her spiritual successors she prefers the grand and distant vista, and does not approach closely to see the outcasts and victims who are part of every great undertaking. She loved "the view of the skyscrapers where you don't see the details," declares the film, unselfconsciously.

This made her a formidable popular writer. She was seriously able to declare that Marilyn Monroe seemed to have come from an ideal, joyful world, that the star was "someone untouched by suffering." The hero of her last novel, Atlas Shrugged,was the direct descendant of Cyrus, the hero of a boy's adventure story she read at the age of 16. Like most libertarians, she had a deeply childish world view.

Never beautiful, Rand's intensity (and searching black eyes) seduced more than a few men. According to Harry Binswager, one of her academic admirers, "her idea of feminity was an admiration of masculine qualities." This was also Hitler's idea of feminity, and Rand's screenplays invariably include an idealized hero or heroine standing on a distant promontory, Leni Riefenstahl-style, but these fascinating parallels are of course not examined in A Sense of Life.

Rand had a powerful, if not searching, intellect. In many on screen interviews seen in the film, she gives apparently convincing answers to her critics. But the answers are always framed in absolutes -- "man wants freedom, suffering has no importance" -- which are essentially empty postulates. But they have an attractive ring.

A Sense of Life is worth seeing because its naive presentation of Rand is consonant with Rand herself. In fact, it feels like nothing so much as an in-house biography of the founder of some fundamentalist religious sect. It acknowledges its subject's imperfections (her infidelity to her husband of 50 years, for example), but only to declare them redeemed by her quest for truth.

Rand was, of course, a lifelong atheist. But her work is a testament to the yearning for belief. The film concludes on a lingering shot of a poster for Atlas Shrugged,"Don't call it hero worship: it's a kind of white heat where philosophy becomes religion." Or, perhaps, the ashes that are left when you turn up the temperature on a new belief system to the point where human community and compassion are burnt away. Conrad Alton, Filmbay Editor.

The evangelical tone is set by filmmaker Michael Paxton, quoted in the press material as saying that he first found Ayn Rand when he was an adolescent trying "to find a book that would answer all of my questions and give my life meaning." A Sense of Life contents itself with interviewing her friends and acolytes. It acknowledges that she was much criticized, and even considered a crank, but her critics don't appear on screen and their views are not explained.

But neither Rand nor the film should be dismissed, if only because she is widely read and her ideas have been deeply influential. They lie behind much neo-conservative commentary, which recasts democracy -- essentially an untidy contest of ideas and interests -- as a secular religion (she called it Objectivism) where competing points of view are greeted with adolescent impatience.

But more particularly, Rand's influence helps explain the concealed romanticism of much right-wing commentary, which replaces iconic figures from other belief systems with buccaneering businessmen and entrepreneurs. As this film unwittingly makes clear, Rand herself was one of the great romantics. A worshipper of Hollywood, and partly successful screenwriter, she laments that the film version of her novel The Fountainhead "lacked the Romanticism of the German films she had loved as a youth." That these films were the precursors of fascism seems to have escaped the notice of Rand and her disciples.

This appealing simplicity, a charming oblivion to her own contradictions, gave Rand a widespread following among those looking for answers, even as it exasperated intellectuals. She believed that each individual has a sacred core of personal talents and dreams which can be expressed in a free society. People may choose to co-operate, but these choices must ultimately serve their self-interest. If an action is truly selfless, she often said, it is "evil." Her reasoning was that selflessness in one's own life can be enlisted by political systems such as communism that call on human beings to sacrifice themselves for the state.

These views were apparently burned into Rand's consciousness by the horrors she witnessed during and after the Russian Revolution -- a period the film recalls through family photographs and archival film footage. She decided that capitalism was the only hope for mankind. "Capitalism leaves every man free to choose the work he likes," she declares on screen, oblivious to the deadening monotony of most people's jobs, not to mention unemployment.

Like her spiritual successors she prefers the grand and distant vista, and does not approach closely to see the outcasts and victims who are part of every great undertaking. She loved "the view of the skyscrapers where you don't see the details," declares the film, unselfconsciously.

This made her a formidable popular writer. She was seriously able to declare that Marilyn Monroe seemed to have come from an ideal, joyful world, that the star was "someone untouched by suffering." The hero of her last novel, Atlas Shrugged,was the direct descendant of Cyrus, the hero of a boy's adventure story she read at the age of 16. Like most libertarians, she had a deeply childish world view.

Never beautiful, Rand's intensity (and searching black eyes) seduced more than a few men. According to Harry Binswager, one of her academic admirers, "her idea of feminity was an admiration of masculine qualities." This was also Hitler's idea of feminity, and Rand's screenplays invariably include an idealized hero or heroine standing on a distant promontory, Leni Riefenstahl-style, but these fascinating parallels are of course not examined in A Sense of Life.

Rand had a powerful, if not searching, intellect. In many on screen interviews seen in the film, she gives apparently convincing answers to her critics. But the answers are always framed in absolutes -- "man wants freedom, suffering has no importance" -- which are essentially empty postulates. But they have an attractive ring.

A Sense of Life is worth seeing because its naive presentation of Rand is consonant with Rand herself. In fact, it feels like nothing so much as an in-house biography of the founder of some fundamentalist religious sect. It acknowledges its subject's imperfections (her infidelity to her husband of 50 years, for example), but only to declare them redeemed by her quest for truth.

Rand was, of course, a lifelong atheist. But her work is a testament to the yearning for belief. The film concludes on a lingering shot of a poster for Atlas Shrugged,"Don't call it hero worship: it's a kind of white heat where philosophy becomes religion." Or, perhaps, the ashes that are left when you turn up the temperature on a new belief system to the point where human community and compassion are burnt away. Conrad Alton, Filmbay Editor.

Você sabia?

- ConexõesFeatures A Marca do Zorro (1920)

Principais escolhas

Faça login para avaliar e ver a lista de recomendações personalizadas

Detalhes

- Data de lançamento

- País de origem

- Central de atendimento oficial

- Idioma

- Também conhecido como

- Ayn Rand: Un sentido de la vida

- Locações de filme

- Empresas de produção

- Consulte mais créditos da empresa na IMDbPro

Bilheteria

- Orçamento

- US$ 1.000.000 (estimativa)

- Faturamento bruto nos EUA e Canadá

- US$ 205.246

- Fim de semana de estreia nos EUA e Canadá

- US$ 26.101

- 16 de fev. de 1998

- Faturamento bruto mundial

- US$ 205.246

- Tempo de duração2 horas 25 minutos

- Cor

- Mixagem de som

- Proporção

- 1.85 : 1

Contribua para esta página

Sugerir uma alteração ou adicionar conteúdo ausente

Principal brecha

By what name was Ayn Rand: A Sense of Life (1996) officially released in Canada in English?

Responda