The Artist: Joachim Patinir was born in the southern Lowlands, either in Dinant or Bouvignes (southeastern Belgium). Although the date of his birth is unknown, it was probably around 1480 or 1485. He entered the Antwerp painters’ guild in 1515 and perhaps married for the first time not long afterwards. Documentation of his second marriage is given in Albrecht Dürer’s diary in which the German artist mentions attending the second wedding and associated festivities in August of 1521. By October 5, 1524, Patinir had died, as documents cite his wife as a widow.

Discussed by Albrecht Dürer in his diary as “the good landscape painter,” Patinir is most famous for introducing landscape as a new genre of art in early-sixteenth-century Antwerp. The burgeoning interest in cartography at the time is linked to Patinir’s panoramic views, and his area of origin along the Meuse River near Dinant and Namur may have been responsible for the unique rocky masses that feature in most of his paintings. It is not known where Patinir trained as a painter or with whom. Perhaps Bosch’s works were influential for their high horizon lines and bird’s-eye vantage point. Gerard David, who joined the Antwerp painters’ guild in 1515 (the same year as Patinir), but probably only to be able to sell his paintings in that thriving art market, may also have provided an important example. Both artists were deeply interested in nature and landscape, and often cited is Patinir’s

Baptism of Christ (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna) that appears to borrow the figures of Saint John the Baptist and Christ from David’s Baptism Triptych (Groeningemuseum, Bruges). He is documented as having collaborated with the Antwerp painter, Quinten Massys, who painted the figures in the Landscape with the

Temptation of Saint Anthony (Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid) and perhaps with Joos van Cleve who may have added the figures of the Virgin and Child in the

Rest on the Flight into Egypt (Gemäldegalerie, Berlin). Patinir likely was called upon to add the landscapes for the backgrounds of paintings by these as well as other Antwerp painters.

In a short career lasting from only about 1515 to 1524, there are a limited number of autograph works, by Robert Koch’s count only nineteen. But Patinir’s influence was enormous, and his followers disseminated his brand of landscape painting well into the sixteenth century. Closely following on his particular style were Lucas Gassel, Herri met de Bles, the Master of the Female Half-lengths, and even the next great landscape painter Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Patinir’s paintings were popular not only in the Burgundian Netherlands, but also were a desirable export product to Spain and Italy.[1]

Given Patinir’s short career, there are difficulties in determining a clear chronology of the works. In this regard, the ground-breaking

Patinir exhibition at the Museo del Prado in Madrid in 2007 provided a wealth of new discoveries about the artist’s working methods and prompted a reevaluation of the attributions and chronology of his oeuvre (see Patinir 2007).

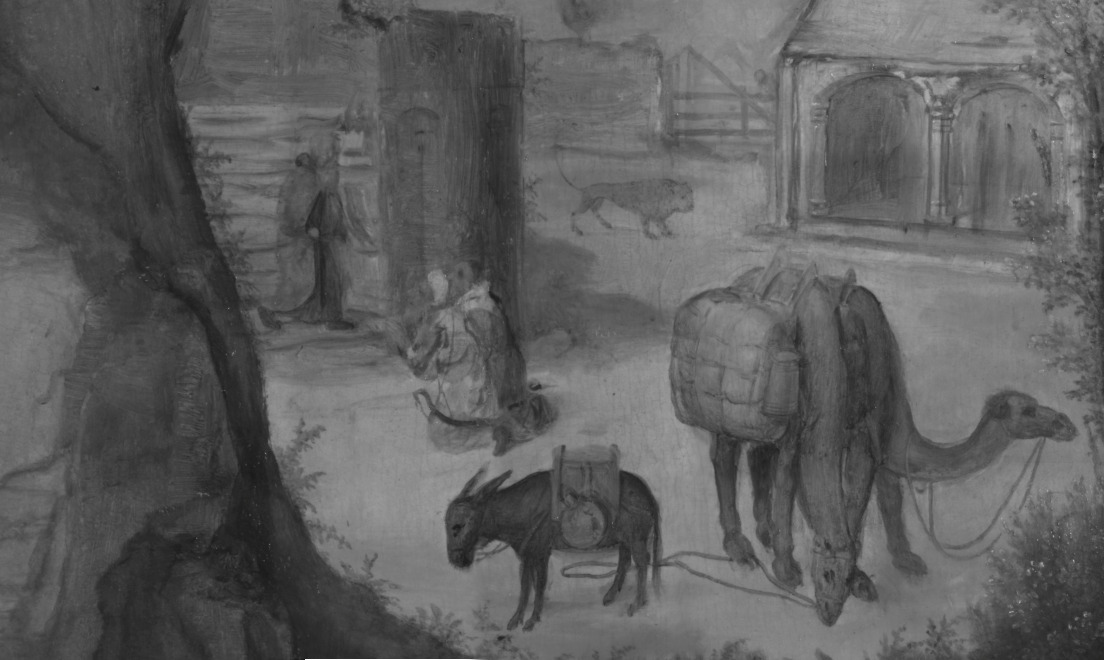

The Painting: This triptych—with a well-preserved surface and totally intact in its original, but refinished frame—is a key work by Patinir. It shows on its individual sections, when open, episodes from the lives of three hermit saints whose spirituality was tested and strengthened by long periods spent alone in the wilderness. On the central panel Saint Jerome is shown self-flagellating his chest with a rock as he meditates on the crucifix before him. In the extensive landscape to the right of the rocky outcropping, Jerome pardons two merchants who had stolen a donkey from the monastery on the hill above. The donkey was to have been guarded by Jerome’s pet lion, who redeemed himself by finding the animal and bringing the merchants to justice. These scenes are taken from Jacobus de Voragine’s

Golden Legend, first compiled between 1259 and 1266, but thereafter translated from the Latin into vernacular languages and widely disseminated throughout Europe in the late fifteenth- and early-sixteenth centuries.[2]

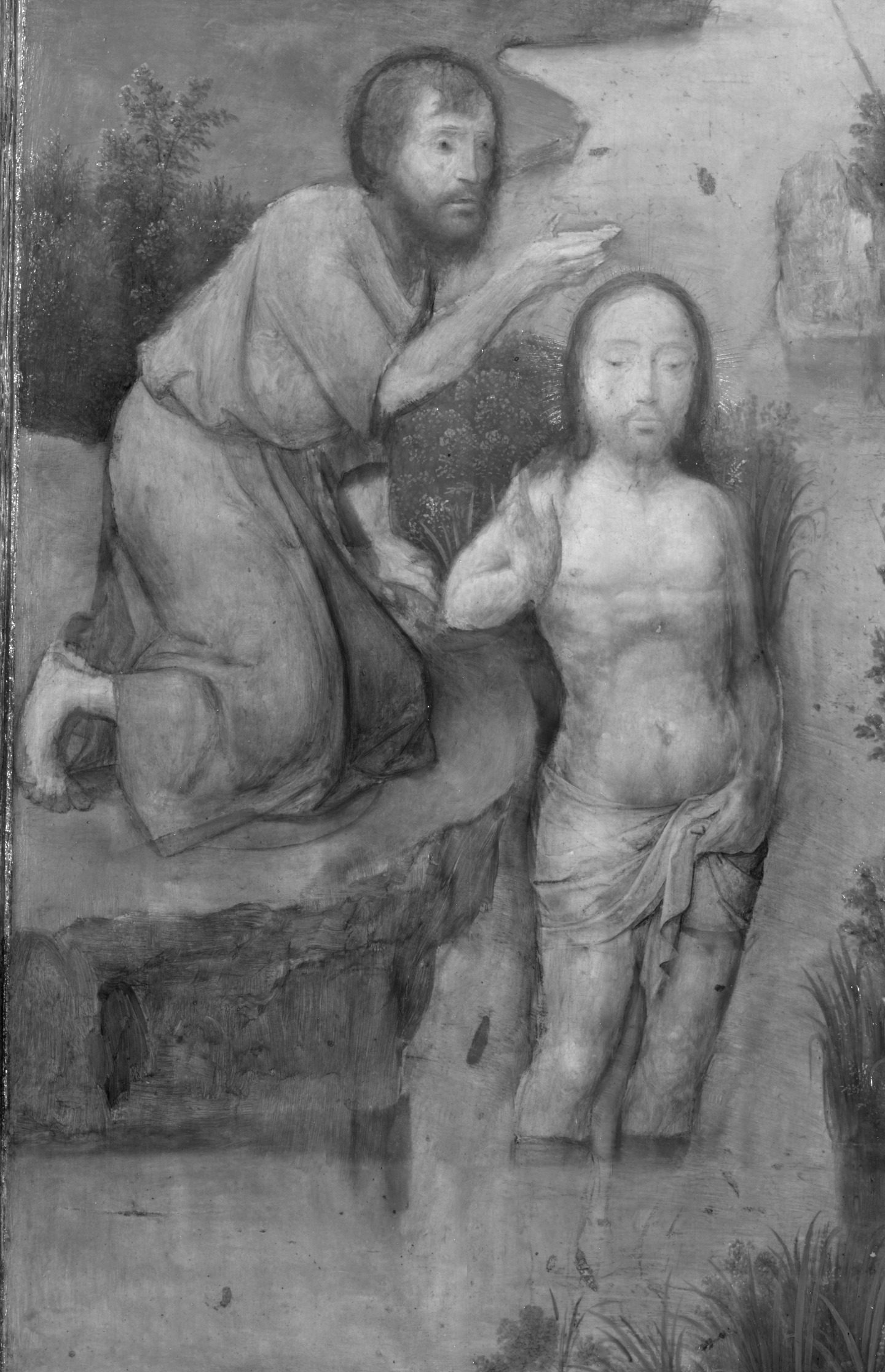

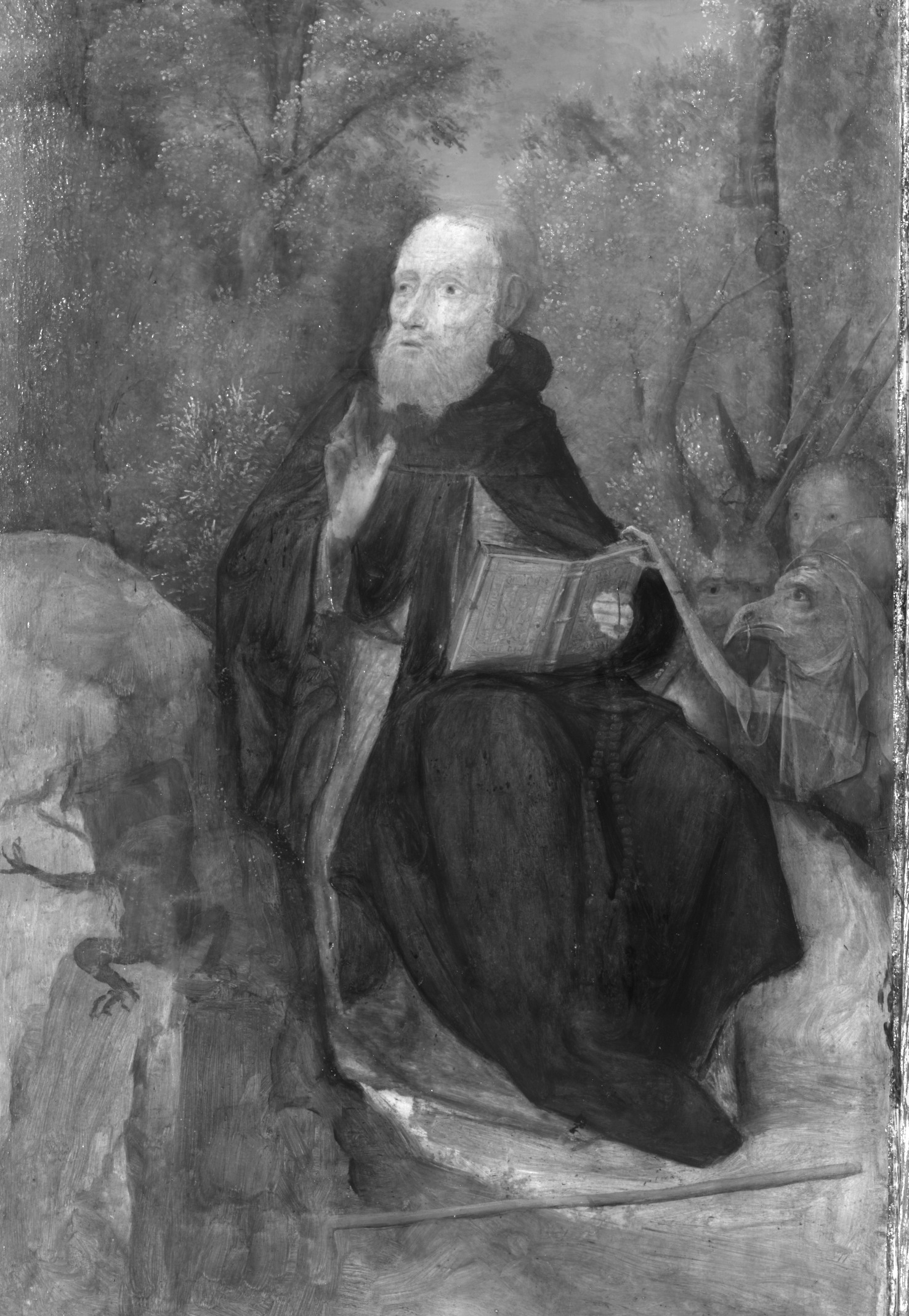

On the left wing are two scenes from the life of Saint John the Baptist, as recounted with differing details in the Gospels: Matthew 3:1–17; Mark 1:4–11; Luke 3: 1–22; and John 1:19–34, 3: 22–36. In the background John preaches to the Jews in the clearing of a forest, while in the foreground he baptizes Christ. God appears in the heavens above, sending forth his blessing through the dove of the Holy Spirit in a radiance of gold, and saying “This is my beloved son, in whom I am well pleased” (Matthew 3:17). The right wing shows Saint Anthony reading the Holy Scriptures and reciting his rosary while enduring the taunting of satanic monsters, as described in the

Golden Legend.[3] Christ on the left wing and Anthony on the right wing both raise their right hands in blessing toward the viewer-worshipper, who would have been positioned in devotion before the altarpiece. The inclusion of these particular hermit saints in the altarpiece must have been dictated by the commission of the triptych, the details of which remain unknown.

When closed, the outside wings display grisaille figures of Saint Anne with the Virgin and Child and Saint Sebald as fictive sculptures in niches. As Saint Anne was much venerated in Germany and Saint Sebald was the patron saint of Nuremberg, it is likely that the triptych was commissioned by south German patrons, perhaps for a monastery. However, by 1674 it was in the collection of Emperor Leopold I in Vienna, and subsequently in the Benedictine monastery of Kremsmünster (near Linz, Austria), where it remained until 1935 when it was sold to The Met through the art dealer Knoedler.

Certainly the most striking feature of the triptych, and a true novelty for its time, is the “worldview” landscape that extends across all three panels. At the beginning of the sixteenth century, landscape painting began to emerge as an independent genre, and Patinir was at the forefront of this development. On his trip to the Netherlands in 1520–21, Albrecht Dürer referred to Patinir as the "good landscape painter"—an early acknowledgment of the artist’s achievements in this new specialization. The emphasis on landscape—featuring it over the saints who are diminished in size—is especially notable when the triptych is compared, for example, to Joss van Cleve’s

The Crucifixion with Saints and a Donor of about 1520 (The Met

41.190.2–a–c) where the holy figures and the Patinir-inspired landscape take up equal space in the composition.

There are unique features of the landscape in Patinir’s development of it. As Gibson observed (1989), there is a certain “indifference to spatial unity” here. The landscape as a whole is seen from above in a bird’s-eye view, while the individually studied components, such as the craggy rocks, buildings, and large trees, are viewed at eye level. A “bold defiance” of atmospheric perspective, allowing the viewer to encounter near and far elements with equal clarity, and a high horizon line unite these disparate views to create an ideal landscape, not a realistic one. Overlapping features of rocks, trees, and hills from the wings to the center piece of the triptych unite the otherwise separate domains of the three saints. As Lynn Jacobs (2012, p. 240) noted, “The linkage communicates the connected nature of their anchorite experiences and unites them as exemplars of virtue and models of the monastic ideal who retreated to the wilderness to escape the sins of the city.”

How these paintings functioned for the devotional practices of the viewer has been addressed by Reindert Falkenburg (1988). The construction of the landscape is marked by a diagonal line that runs from the upper left mountains to the lower right plains, thus separating the highlands from the lowlands. Falkenburg (1988, pp. 85–92, 98–99, 105–12) relates this dichotomy to the writings of Saint Augustine and the contrast between the world of sin (

civitas terrena) and the way of salvation to the City of God (

civitas Dei). He links this with the so-called pilgrimage of life in which one is constantly striving toward the ultimate goal of the Heavenly Jerusalem. The arduous travel through the rocky highlands represents the challenging road of penitence leading to salvation. The lowlands make no such demands, instead offering the easy route and occasions for succumbing to sinful ways. Long known from the Classical world as the Herculean choice, this is the test of Virtue over Vice, here communicating the human predicament that is replayed through the ages. This extraordinary triptych can be viewed and appreciated on many levels not only as a beautiful landscape view but also as conveying deeper meaning in both religious and philosophical terms.

The Attribution and Date: Max J. Friedländer (1936) was among the first to recognize this triptych as the work of Patinir, a view seconded by Wehle (1936) and thereafter followed by most other scholars (see References). Only Cuttler and Dunbar (1969) considered the triptych lacking the features of handling and execution so appreciated in Patinir’s paintings, finding it “stiff, hard, or fussy…” instead. It is one of only two extant triptychs attributed to Patinir and his workshop, the other being the

Triptych of Saints Jerome, John the Baptist, Anthony, and Mary Magdalen of about 1517–24 (Private collection, Switzerland).[4] Perhaps the artist recognized the advantage of painting vast landscapes on one uninterrupted field rather than on three separate panels artificially joined together (Jacobs 2012, p. 238).

Patinir joined the Antwerp painters’ guild in 1515, and thus had a quite short career that extended from about 1515 until his death in 1524. Considering this as well as the extraordinary impact the artist had on the genre of landscape painting, resulting in many contemporary copyists and followers, it is not surprising that there have been challenges in creating a chronology for Patinir’s oeuvre. Previously, The Met’s triptych was considered a mature work and dated to around 1518 (see, for example, Koch 1968)—closer in time to the

Landscape with the Baptism of Christ of about 1521–24 in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, with which it shares the motif of Saint John baptizing Christ. However, a thorough technical examination of the triptych in preparation for the landmark Patinir exhibition at the Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid, in 2007 offered new evidence about the working techniques and stylistic traits of the triptych (Ainsworth and Thomas 2007; see also Technical Notes). Moreover, it was possible to compare these results with those gathered for other paintings by Patinir studied for the exhibition, leading to the conclusion that The Met triptych is most likely among the earliest works, dating about 1515. This is not disputed by the dendrochronological examination by Peter Klein that establishes a date after 1494 (Klein 2007).

Comparable to other paintings by Patinir, there is a very sketchy underdrawing, made in a crumbly drawing material like black chalk. This preliminary sketch defines the main compositional features including the high horizon line, the placement of the essential figures, and the rough indication of prominent landscape and architectural elements. These characteristics of execution are present in other paintings securely attributed to Patinir, such as the

Landscape with Saint Jerome about 1516–17 and the

Rest on the Flight into Egypt of about 1518–20 (see fig. 1 above; both in the Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid), and the

Landscape with the Martyrdom of Saint Catherine of about 1515 and the

Baptism of Christ of about 1521–24 (both in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna).[5]

Documentary and technical evidence about Patinir’s oeuvre points to the landscape artist’s collaboration with figural painters, especially Quentin Massys, in some of his paintings such as the Prado

Rest on the Flight into Egypt and

Landscape with the Temptation of Saint Anthony.[6] In these cases, the prominent figures are painted on top of the preliminary landscape layer. In The Met’s triptych, instead, a very rough reserve is left for the saints in the foreground where there is overlapping of the figures onto the painted landscape background (figs. 2–4). This organic process of back and forth to secure the final painted image strongly suggests that the figures were painted by the same hand, that is, Patinir himself. The monsters surrounding Saint Anthony on the right panel may have been either an afterthought or possibly added by another artist, as there is no reserve for these (fig. 4). For

Saint Anne with the Virgin and Child as well as for

Saint Sebald on the outside wings there is an extremely loose and sketchy underdrawing that gives only a vague idea of the trompe-l’oeil statues to be painted in grisaille (figs. 5–8).

The landscape painting reveals Patinir’s typical efficient method of covering large areas of the composition with varied forms of rocks, lowlands, rivers, and forests. Beginning with relatively flat tones, and building up areas with lighter colors, Patinir then worked in the details of forms swiftly, sometimes using -in wet brushstrokes (see Technical Notes). Many small details were not planned in the underdrawing but simply painted in at the last stages with minimal brushwork. The working methods evident in The Met’s triptych—as is true elsewhere in his oeuvre—suggests that Patinir made preliminary drawings on paper for his compositions and had at hand many individual studies of motifs that served him well as he worked up the final details of his paintings, judiciously placing them to achieve his idealized presentation of landscape. Although no undisputed drawings on paper by Patinir remain, they surely must have existed.[7]

Maryan W. Ainsworth 2023

[1] For further on the biography of Patinir, see Ludwig Baldass, “Die Niederländische Landschaftsmalerei von PAtinir bis Bruegel,“

Jahrbuch der kunsthistorischen Sammlungen in Wien 34 (1918), pp. 111–57; Max J. Friedländer,

Early Netherlandish Painting, vol. 9, 1931; vol. 9, part 2, 1973, Leiden and Brussels, pp. 99-110; Robert Koch,

Joachim Patinir, Princeton, 1968;

Patinir, Essays and Critical Catalogue, Alejandro Vergara, ed., exh. Cat. Mjuseo del Prado, Madrid, 2007.

[2]

The Golden Legend of Jacobus de Voragine, translated from the Latin by Granger Ryan and Helmut Ripperger, New York, 1969, pp. 587–92.

[3] Ibid., pp. 99–103.

[4] A

Rest on the Flight into Egypt Triptych of about 1520 (National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo) by a follower of Patinir shows a featured landscape only in its central panel and not across all three panels.

[5] See

Patinir 2007, nos. 20, 5, 16, and 11 for further information on the technical material concerning these paintings.

[6] See

Patinir 2007, nos. 5, 14.

[7] See “Patinir’s Draughtsmanship Reconsidered” by Stefaan Hautekeete in

Patinir 2007, pp. 135–47.