IMDb RATING

7.7/10

13K

YOUR RATING

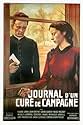

A young priest taking over the parish at Ambricourt tries to fulfill his duties even as he fights a mysterious stomach ailment.A young priest taking over the parish at Ambricourt tries to fulfill his duties even as he fights a mysterious stomach ailment.A young priest taking over the parish at Ambricourt tries to fulfill his duties even as he fights a mysterious stomach ailment.

- Director

- Writers

- Stars

- Nominated for 1 BAFTA Award

- 7 wins & 3 nominations total

Adrien Borel

- Priest of Torcy (Curé de Torcy)

- (as Andre Guibert)

Rachel Bérendt

- Countess (La Comtesse)

- (as Marie-Monique Arkell)

Antoine Balpêtré

- Dr. Delbende (Docteur Delbende)

- (as Balpetre)

Gaston Séverin

- Canon (Le Chanoine)

- (as Gaston Severin)

Serge Bento

- Mitonnet

- (as Serge Benneteau)

Germaine Stainval

- La patronne du café

- (uncredited)

François Valorbe

- Bit Role

- (uncredited)

- Director

- Writers

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

7.713.4K

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Featured reviews

10msultan

Excellent

This must be one of the most touching movies I have seen in my

life. I would rank it high up there with movies like The Bicycle Thief.

It depicts human frailty at its best (and consequently, worst) in a

very pure and painfully real light. I think this this is definitely a movie that cannot be remade, the

priest's expressions and anxiety are too perfect to be replaced. I

only wish I watched a good copy (mine skipped scenes and cut

dialogues). Regardless, this movie is definitely an all-time best,

and deals with such personal issues at such a personal level that

it can never age. It touches the soul straight on and literally takes

one's breath away.

life. I would rank it high up there with movies like The Bicycle Thief.

It depicts human frailty at its best (and consequently, worst) in a

very pure and painfully real light. I think this this is definitely a movie that cannot be remade, the

priest's expressions and anxiety are too perfect to be replaced. I

only wish I watched a good copy (mine skipped scenes and cut

dialogues). Regardless, this movie is definitely an all-time best,

and deals with such personal issues at such a personal level that

it can never age. It touches the soul straight on and literally takes

one's breath away.

Pretty much perfect.

*Diary of a Country Priest* is a nearly perfect film. Made in 1950, this film benefits from Bresson being at the height of his powers. As he aged, the slow, measured, static style became more and more mannered, or more and more intolerable, shall we say. But here he doesn't go overboard: the mood is portentous rather than pretentious. And in any case, it's not as slow as you may think: there are probably hundreds of cuts in the film (this ain't no Carl Th. Dreyer movie). Along those lines, Bresson's method of adaptation -- which is to distill the ESSENCE of the chosen work -- is stringently economical and pared to the bone. In other words, the thing doesn't simply dawdle along. Based on a 1930's novel by a right-wing Euro novelist, *Diary* details the sad experiences of a young priest with health problems who is assigned to a new parish. The villagers treat the young man with hostility and downright scorn. Sensing and resenting the new priest's obvious holiness (everybody hates a saint), they ridicule him, shut him out of their confidences, send threatening anonymous notes ("I feel sorry for you, but GET OUT") . . . to all of which our hero responds with a sort of confused empathy. Meanwhile, Bresson uses a striking narrative device: we see the priest writing in his diary, while VOICING OVER what he's writing, and then there's a cut to a scene which SHOWS the action the priest has just been writing (and narrating) about. This complex, layered style proves to be more than a fair trade-off for the paucity of actual narrative incidents. We're invited to ponder an event's significance -- a lucky thing, because the action is quite often so psychologically complex that we need room to breathe, to think things over. Don't presume to form an opinion of *Diary* until you've seen it at least twice. Sounds like homework, I know, but so does *King Lear*. Great art IS homework.

Perhaps the film's true value is its delineation of just how stagnant and unpleasant little towns can be. Again Bresson is inventive: rather than simply show us the putrid little village, the director instead opts for an oblique approach, inviting us to IMAGINE just how putrid the village actually is, usually by heightening off-screen sound effects. Quite often, we hear unpleasant things like motorcycles backfiring, rakes running over asphalt, crows screeching, mean-spirited giggling outside a window, iron gates slamming shut, and so on.

And finally, it must be said that it's surprising how avowed agnostic directors make the most persuasive religious movies. In my view, this film and Dreyer's *Ordet* remain the greatest films about Christianity in the history of cinema (the conversion scene in the middle of *Diary* might prompt you to go to church next Sunday). Anyway, *Diary of a Country Priest* is an unassailable, influential masterpiece that's a MUST-OWN for the true cineaste, and a possible education in art for everybody else. Get the new Criterion edition, watch it twice, and listen to Peter Cowie's commentary. I assure you that it won't be a waste of your time.

Perhaps the film's true value is its delineation of just how stagnant and unpleasant little towns can be. Again Bresson is inventive: rather than simply show us the putrid little village, the director instead opts for an oblique approach, inviting us to IMAGINE just how putrid the village actually is, usually by heightening off-screen sound effects. Quite often, we hear unpleasant things like motorcycles backfiring, rakes running over asphalt, crows screeching, mean-spirited giggling outside a window, iron gates slamming shut, and so on.

And finally, it must be said that it's surprising how avowed agnostic directors make the most persuasive religious movies. In my view, this film and Dreyer's *Ordet* remain the greatest films about Christianity in the history of cinema (the conversion scene in the middle of *Diary* might prompt you to go to church next Sunday). Anyway, *Diary of a Country Priest* is an unassailable, influential masterpiece that's a MUST-OWN for the true cineaste, and a possible education in art for everybody else. Get the new Criterion edition, watch it twice, and listen to Peter Cowie's commentary. I assure you that it won't be a waste of your time.

Faith in the midst of tribulation

Robert Bresson's masterfully composed film, Diary of a Country Priest, is in complete alinement with his other work. Bresson was a very spiritual filmmaker, and he weaves the fascinating tale of a young parish priest who sets up shop in a hostile environment with such grave and minimalistic purity. Bresson relied upon naturalistic performances from non-actors. He thrived on this way of film-making, and he was the master of it. Diary of a Country Priest details the sublime detachment between a young priest and his new congregation. His sickness further alienates him from the parishoners, who act in a hostile manner at what they see as his negated passivity. He falls back on his faith as his source of strength, but even it is dwindling. The only person who he is able to commune with is a young girl who confides in him. The film is a touching portrait of the stasis of mankind, whether you feel that religion is key and of necessity, or if you feel it is a farce.

The kind of integrity and faith so strong and real, it frightens even the church

A young priest has been assigned his first parish in a village somewhere in the North of France. Right from the first, essential opening shot in beautiful black and white, we instinctively get a sense of his isolation from any other human being. As the final credits rolled by, I don't know why I had the impulse to restart the DVD, and I watched the first 5 minutes of the movie again, realising just how much of a harbinger of extreme loneliness the opening frames are. Diary of a Country Priest is in good part about loneliness - the extreme physical, emotional and intellectual isolation of those who embark on an earnest mission, with an inability to compromise and a sincerity (with its resulting emotional vulnerability) which both frightens and repulses those who aren't ready to receive it. I was especially thankful to Bresson for having left us with a film about a priest which didn't involve his tiresome sexual issues in any shape or form - what a refreshing change! In the role of the young parish priest of Ambricourt, young Claude Laydu was in his debut role here - though he very occasionally shows his inexperience as an actor, he is nonetheless remarkable in the title role, and his sensitive, silently suffering, candid boyish face will remain with me for quite a while. It's extraordinary that such a movie, so completely devoid of any mass appeal or commercial potential, should have found someone willing to fund it. This kind of thing restores one's faith in the integrity and vision of certain cinematic enterprises.

Fight to keep faith

This is a deeply religious film. It conveys anguish and despair. It may seem depressing but you find hope. It is a great movie made with a very slow rhythm that fits perfectly with the life and the thoughts of the priest. Each scene fades to black slowly into the next and leaves you waiting with that sense of "nothing" that tortures the priest. It is intense in the dialogs, although you may have to see it several times before you can really "catch" them. The struggle to believe, to persevere, to find, to know is common to all the characters in different ways. "Before me, a black wall" says th priest; I think, we all had similar thoughts, at least once in our lives.

Did you know

- TriviaThe hand and handwriting in the film belong to Robert Bresson.

- Quotes

[subtitled version]

Countess: Love is stronger than death. Your scriptures say so.

Curé d'Ambricourt: We did not invent love. It has its order, its law.

Countess: God is its master.

Curé d'Ambricourt: He is not the master of love. He is love itself. If you would love, don't place yourself beyond love's reach.

- ConnectionsFeatured in Histoire(s) du cinéma: Les signes parmi nous (1999)

- How long is Diary of a Country Priest?Powered by Alexa

Details

Box office

- Gross US & Canada

- $47,000

- Opening weekend US & Canada

- $7,674

- Feb 27, 2011

- Gross worldwide

- $47,000

- Runtime

- 1h 35m(95 min)

- Color

- Aspect ratio

- 1.37 : 1

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content