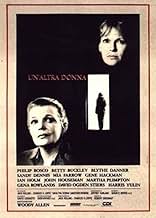

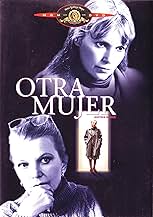

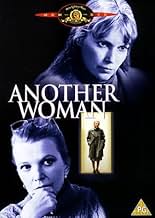

Facing a mid-life crisis, 50-year-old college dean Marion Post takes a sabbatical and rents an apartment next to a psychiatrist's office to write a new book, then is drawn to the plight of a... Read allFacing a mid-life crisis, 50-year-old college dean Marion Post takes a sabbatical and rents an apartment next to a psychiatrist's office to write a new book, then is drawn to the plight of a pregnant woman seeking that doctor's help.Facing a mid-life crisis, 50-year-old college dean Marion Post takes a sabbatical and rents an apartment next to a psychiatrist's office to write a new book, then is drawn to the plight of a pregnant woman seeking that doctor's help.

- Awards

- 1 win & 3 nominations total

- Director

- Writer

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

Featured reviews

This is by far my favorite Woody Allen straight drama (most of his other "serious" films, like Crimes and Misdemeanors and Husbands & Wives, have comedic moments). His third "heavy film" (after Interiors and September) is chamber drama, beautifully acted and directed. Most of the elements found in Allen's other post "Annie Hall" films are here (the upper crust Manhattan intellectuals, dysfunctional relationships), but what's missing are the laughs. The film is very serious stuff, involving repressed emotions and alienation. There is simply no place for Woody's usually nervous character in Another Woman. You can still tell that this is one of his films because of the characterizations. Gena Rowlands is in nearly every scene and is classy, as usual, and the rest of the ensemble cast is just as good. My favorites were Gene Hackman and Ian Holm. The title is fairly clever as well; it doesn't refer to what you might think.

Devastating, unlike anything I've seen from Woody Allen so far. This was a very quiet, deliberately paced exploration into a woman facing a mid-life crisis, played with extraordinary skill by Gena Rowlands. It leaned maybe a little too much on narration when it could have utilized her talent as an actress instead, but that's a small complaint when the final result is so powerful.

Rowlands' Marion Post rents an apartment in order to work on her novel and, through hearing the patients of the psychiatrist's office next door, slowly begins to examine her life and the choices that she has made. We see her interact with those surrounding her, be it her husband, her daughter, her brother, but she always feels a level removed from all of them. Over the years she has isolated herself from everyone around her and examines them rather than interacts, and Rowlands plays this with a knowledge so fitting and serene.

There's an extended dream sequence a little over halfway through the picture that is one of the most surreal, emotional and illuminating experiences I've had in a Woody Allen picture and one of my favorite moments in the twenty or so films of his I've seen. It imagines her life as a stage play that she watches take place, and it opens the world back up to Marion, which is displayed in master strokes on the all-telling face of Rowlands. She gives a performance for the ages here, working mostly from the inside out, although there are a few devastating scenes of her letting herself fall apart.

I was surprised at how little Mia Farrow was in it, given that she's on the cover for it and the plot synopsis makes her part seem a lot more major, but she manages to leave an impression, although the most surprising of the supporting cast was Gene Hackman. I'm used to seeing him (and loving him) in varying crime pictures, so it was nice to see him take on a more grounded and every day character, which despite only appearing for a brief time he manages to leave a lasting impression with his emotionally conflicted portrayal. You can really feel this character that he displays, feel his love and heartache in every breath.

Still, the film absolutely belongs to Rowlands, who resonated so deeply inside of me and will surely stick there for a while. She knocks it out of the park in a film that is so unique, cerebral and magnificent from Woody Allen.

Rowlands' Marion Post rents an apartment in order to work on her novel and, through hearing the patients of the psychiatrist's office next door, slowly begins to examine her life and the choices that she has made. We see her interact with those surrounding her, be it her husband, her daughter, her brother, but she always feels a level removed from all of them. Over the years she has isolated herself from everyone around her and examines them rather than interacts, and Rowlands plays this with a knowledge so fitting and serene.

There's an extended dream sequence a little over halfway through the picture that is one of the most surreal, emotional and illuminating experiences I've had in a Woody Allen picture and one of my favorite moments in the twenty or so films of his I've seen. It imagines her life as a stage play that she watches take place, and it opens the world back up to Marion, which is displayed in master strokes on the all-telling face of Rowlands. She gives a performance for the ages here, working mostly from the inside out, although there are a few devastating scenes of her letting herself fall apart.

I was surprised at how little Mia Farrow was in it, given that she's on the cover for it and the plot synopsis makes her part seem a lot more major, but she manages to leave an impression, although the most surprising of the supporting cast was Gene Hackman. I'm used to seeing him (and loving him) in varying crime pictures, so it was nice to see him take on a more grounded and every day character, which despite only appearing for a brief time he manages to leave a lasting impression with his emotionally conflicted portrayal. You can really feel this character that he displays, feel his love and heartache in every breath.

Still, the film absolutely belongs to Rowlands, who resonated so deeply inside of me and will surely stick there for a while. She knocks it out of the park in a film that is so unique, cerebral and magnificent from Woody Allen.

There was a certain period in Woody Allen's career when he was trying desperately to imitate Ingmar Bergman's work. It rarely worked, and often turned out disasters like the execrable September. Another Woman is a riff on Bergman's Wild Strawberries: a college professor, played by Gena Rowlands, is past fifty and looking back on and reliving key events in her life as her present life is falling apart. The film is quite stagy at times, just as it was in September, Allen's previous film. He seems to think that adds something, but it really doesn't. One other problem Another Woman has is a couple of very clunky scenes, and a few poor bit performers, which were much bigger problems in September, which was actually the last Allen film that I saw and the one that made me subconsciously avoid him for the past several months. Allen's script here is excellent. He has produced an excellent character study which is probably unsurpassed in all of his other films that I've seen. The lead actors are wonderful here, Rowlands, Ian Holms, Blythe Danner, Sandy Dennis, and Gene Hackman. Allen's use of piano music is beautifully touching. It all adds up to a very touching and sad little film. It might not be Woody's best film, but it ought to be better respected and known. 8/10.

10canadude

It's worth noting that in 1978, ten years before he made "Another Woman," Woody Allen created another quiet film, a drama with prominent Bergmanesque influences. The film was called "Interiors," and it was a tribute, or an American take on Bergman's "Cries and Whispers." "Interiors" examined the relationships of three sisters and their husbands in the face of the divorce of their dominant mother and detached father. The film essentially detailed the fall of "interiors," or illusory worlds created by the dominant mother in the face of tragedy and loneliness.

"Another Woman," made ten years later, shares similar themes with "Interiors," but it is more akin to Bergman's "Wild Strawberries" than to "Cries and Whispers." It is a story of a university professor, played spectacularly by Gena Rowlands, in whom something stirs when she overhears a therapy session with a young 30-something woman who is discontent with her life. The professor, Marion, feels an emptiness rise inside her - an emptiness that had settled there years before, that she can consciously feel now. Little by little, like in "Interiors," the world she has constructed for herself, a cold, cerebral world, deconstructs.

Marion despairs, enters into conflicts with herself, and questions endlessly trying to reason her way out of her malaise. But the cure for her malaise is not rational resolution and she, realizing that her strongest characteristic (namely her rational intelligence) is not enough to untangle what worries her, finds herself entirely helpless in the face of an unraveling existence.

Her drama is very much like the drama of Professor Isak Borg from Bergman's film, a man on his way to receive a medal for his lifetime achievements. And, on the road, he also succumbs to the same malaise as Marion, the same questioning and the same painful re-evaluation. The horror shared by both Marion and Professor Borg, of course, is that despite their highly lauded accomplishments and their intellectual self-satisfaction, they feel void. There must, in other words, be something else to life than strictly intellectual work, however satisfying it may be.

In Bergman (both "Cries and Whispers" and "Wild Strawberries") and in Allen (both "Interiors" and "Another Woman") life falls under question. The entire existence is evaluated, its worth and meaning doubted. In "Interiors" and "Cries and Whispers," however, the meaninglessness pervades everything in the films - the dialogues, behaviors and even visuals. The sisters in "Interiors" shatter the mother's reality and find nothingness - they continue as they were, much like the two sisters in "Cries and Whispers" for whom the death of their young sister changed absolutely nothing, and only confirmed their beliefs about the world.

However, "Another Woman" is not as stark (though it is stark indeed at times). Marion grabs at the chance to re-evaluate the life she feels she painfully wasted and tries to start again. It's not a false choice, or a gimmick on Allen's part, but it's a true depiction of Marion's sincere desire to continue to struggle because her life does have value for her. She rediscovers a passion for the struggle and her motivation is the same curiosity that made her go through the questioning process in the first place.

"Another Woman" is a testament to the fact that Woody Allen was still at the top of his game in the late 1980s. It is a brilliant, honest and (surprisingly) warm film. It is not a remake or rip-off of Bergman's work, though it is highly influenced by him (which shouldn't seem so surprising to anyone, because Bergman himself was influenced by the most basic questions of existence). "Another Woman" is an existential film that is both uncompromising and not hopeless. It's one of my favorite Woody Allen films and it reveals to us not only a great American director, but one whose films are of worldly greatness.

"Another Woman," made ten years later, shares similar themes with "Interiors," but it is more akin to Bergman's "Wild Strawberries" than to "Cries and Whispers." It is a story of a university professor, played spectacularly by Gena Rowlands, in whom something stirs when she overhears a therapy session with a young 30-something woman who is discontent with her life. The professor, Marion, feels an emptiness rise inside her - an emptiness that had settled there years before, that she can consciously feel now. Little by little, like in "Interiors," the world she has constructed for herself, a cold, cerebral world, deconstructs.

Marion despairs, enters into conflicts with herself, and questions endlessly trying to reason her way out of her malaise. But the cure for her malaise is not rational resolution and she, realizing that her strongest characteristic (namely her rational intelligence) is not enough to untangle what worries her, finds herself entirely helpless in the face of an unraveling existence.

Her drama is very much like the drama of Professor Isak Borg from Bergman's film, a man on his way to receive a medal for his lifetime achievements. And, on the road, he also succumbs to the same malaise as Marion, the same questioning and the same painful re-evaluation. The horror shared by both Marion and Professor Borg, of course, is that despite their highly lauded accomplishments and their intellectual self-satisfaction, they feel void. There must, in other words, be something else to life than strictly intellectual work, however satisfying it may be.

In Bergman (both "Cries and Whispers" and "Wild Strawberries") and in Allen (both "Interiors" and "Another Woman") life falls under question. The entire existence is evaluated, its worth and meaning doubted. In "Interiors" and "Cries and Whispers," however, the meaninglessness pervades everything in the films - the dialogues, behaviors and even visuals. The sisters in "Interiors" shatter the mother's reality and find nothingness - they continue as they were, much like the two sisters in "Cries and Whispers" for whom the death of their young sister changed absolutely nothing, and only confirmed their beliefs about the world.

However, "Another Woman" is not as stark (though it is stark indeed at times). Marion grabs at the chance to re-evaluate the life she feels she painfully wasted and tries to start again. It's not a false choice, or a gimmick on Allen's part, but it's a true depiction of Marion's sincere desire to continue to struggle because her life does have value for her. She rediscovers a passion for the struggle and her motivation is the same curiosity that made her go through the questioning process in the first place.

"Another Woman" is a testament to the fact that Woody Allen was still at the top of his game in the late 1980s. It is a brilliant, honest and (surprisingly) warm film. It is not a remake or rip-off of Bergman's work, though it is highly influenced by him (which shouldn't seem so surprising to anyone, because Bergman himself was influenced by the most basic questions of existence). "Another Woman" is an existential film that is both uncompromising and not hopeless. It's one of my favorite Woody Allen films and it reveals to us not only a great American director, but one whose films are of worldly greatness.

If there is a moral to Woody Allen's ANOTHER WOMAN, it is that we should live our lives with passion, spontaneity and optimism. Ironically, these are the very elements that are noticeable missing from the film. ANOTHER WOMAN seems to be selling products it doesn't have in stock, let alone on display.

ANOTHER WOMAN is an immaculate movie; sensitively acted, concisely written and lovingly filmed. But like so many of Allen's "serious" films, it is cold and strangely impersonal. It is Woody standing back and looking at someone else's life, composing a precise picture, but with a hands-off, leave-no-fingerprints approach. It is one of those films that is so easy to admire, but very difficult to embrace. It desperately wants to touch you, but refuses to come within touching distance. The film's central character is described thus: "She's just a little judgmental. You know, she sorta stands above people and evaluates them." That is how Allen approaches his characters here, like they're specimens.

There is, of course, two Woody Allens: the comedy genius and the always aspiring dramatist. Most of his comedies are pretty good, but the best are those that let the serious Woody sneak into the film and give the material backbone, as in ANNIE HALL, MANHATTAN, STARDUST MEMORIES and DECONSTRUCTING HARRY. He allows the serious Woody to make cameo appearances in his comedies, but when he sets his sites on meaningful drama, the funny Woody is barred from the set. It is as though Allen is afraid that so much as a smile will break the mood and make people forget just how serious his intentions are. He so easily mocks intellectual thought in his comedies, that he seems to have no faith in his ability to "be serious" and mean it. As such his serious comedies are alive and filled with insight, while his serious dramas are filled with pretense. How seriously can one take a line like "I shouldn't have seduced you. Intellectually, that is."? I mean, who the heck talks like that? In his comedies, such dialogue shows how pretentious the characters are; in his dramas, it seems meant to show just how sincere the characters are.

And words are an important element of ANOTHER WOMAN. Allen's dialogue and narration is eloquent and sophisticated, but stiff and formal. Even when discussing their deepest feelings or expressing anger or reliving joyous moments in their lives, all the characters speak as though they are discussing the terms of their life insurance policies. There is a solemn emptiness to the tone of the film; even at the end, when Marion tries to make amends for past failings, she seems to be negotiating a contract, not saying "Let's start again." Such pompous droning seems designed to reflect the tone of the characters' lives; but the end result is monotonous and deadening, rather than being poetic and compelling.

The film does have a clever conceit: the always marvelous Gena Rowlands plays Marion Post, a professor of philosophy, who sublets an apartment to serve as an office where she can write her latest book. A quirk in the ventilation system allows her to inadvertently eavesdrop on the conversations going on next door. The next apartment is the office of a psychiatrist, who counts among his patients a young pregnant woman, played by Mia Farrow. The young woman discusses at length her sorrowful life and suicidal impulses. Because she identifies with the younger woman's feelings of loneliness and alienation, Marion becomes obsessed with eavesdropping on the sessions and uses the situation as a springboard for reevaluating her own life.

It is significant that just as Allen tells the story from a sterile distance, Marion reviews her life only indirectly, though voice-overs, flashbacks, dreams and even symbolic stage productions. Even her psychoanalysis is conducted through a surrogate, Farrow's character, who is rather obviously named Hope. Much of the interaction with other characters occurs in Marion's mind. And rather predictably, Marion's journey of self discovery is, well, rather predictable. She discovers -- as protagonists in this sort of film always discover -- that her successful career and her well-ordered life are a facade hiding her empty relationships and assorted personal failures. Her life of satisfied accomplishment is meaningless and the trust, love and respect she believes she shares with others are delusions. It's like IT'S A WONDERFUL LIFE in reverse: Just as the angel Clarence acts as George Bailey's conscience to show him how valuable his life has been, Hope acts as Marion's conscience to reveal how empty her life as become.

ANOTHER WOMAN has a counterpart in Allen's 2003 film, ANYTHING ELSE; another film with an obvious doppelganger. The former is about a woman who encounters her younger alter ego and reevaluates her past choices, while the latter is about a young man whose encounters with his older alter ego (played by Woody Allen) effects the choices that will shape his future. The same basic story is approached from opposite directions.

It's dangerous to speculate, but it seems that Allen made ANOTHER WOMAN during a time in his life when he was hugely admired for his accomplishments and he was deeply involved in a relationship with Mia Farrow and her extended family. Certainly Farrow's playing a pregnant woman and Marion's second thoughts over placing career over personal relationships seem to suggest a parallel. By contrast, ANYTHING ELSE, made a decade and a half later, finds Allen's character playing a mentor at a time when he is apparently happily married to a much younger woman, and where his status as a filmmaker is more iconic than in vogue. As such, his surrogate changes from being the central figure to the sadder but wiser voice of experience.

Both films are steeped in regret, but make an effort to end in an upbeat fashion. But while ANOTHER WOMAN is an accomplished, polished work striving for a cool perfection, it is not persuasive in its attempt to inspire us with optimism. ANYTHING ELSE is rambling and unfocused and, well, sloppy, but its optimism is honest and funny. ANOTHER WOMAN is about getting another chance, but there is no reason to believe that anything will really change in Marion's tight, introspective little life.

ANOTHER WOMAN is an immaculate movie; sensitively acted, concisely written and lovingly filmed. But like so many of Allen's "serious" films, it is cold and strangely impersonal. It is Woody standing back and looking at someone else's life, composing a precise picture, but with a hands-off, leave-no-fingerprints approach. It is one of those films that is so easy to admire, but very difficult to embrace. It desperately wants to touch you, but refuses to come within touching distance. The film's central character is described thus: "She's just a little judgmental. You know, she sorta stands above people and evaluates them." That is how Allen approaches his characters here, like they're specimens.

There is, of course, two Woody Allens: the comedy genius and the always aspiring dramatist. Most of his comedies are pretty good, but the best are those that let the serious Woody sneak into the film and give the material backbone, as in ANNIE HALL, MANHATTAN, STARDUST MEMORIES and DECONSTRUCTING HARRY. He allows the serious Woody to make cameo appearances in his comedies, but when he sets his sites on meaningful drama, the funny Woody is barred from the set. It is as though Allen is afraid that so much as a smile will break the mood and make people forget just how serious his intentions are. He so easily mocks intellectual thought in his comedies, that he seems to have no faith in his ability to "be serious" and mean it. As such his serious comedies are alive and filled with insight, while his serious dramas are filled with pretense. How seriously can one take a line like "I shouldn't have seduced you. Intellectually, that is."? I mean, who the heck talks like that? In his comedies, such dialogue shows how pretentious the characters are; in his dramas, it seems meant to show just how sincere the characters are.

And words are an important element of ANOTHER WOMAN. Allen's dialogue and narration is eloquent and sophisticated, but stiff and formal. Even when discussing their deepest feelings or expressing anger or reliving joyous moments in their lives, all the characters speak as though they are discussing the terms of their life insurance policies. There is a solemn emptiness to the tone of the film; even at the end, when Marion tries to make amends for past failings, she seems to be negotiating a contract, not saying "Let's start again." Such pompous droning seems designed to reflect the tone of the characters' lives; but the end result is monotonous and deadening, rather than being poetic and compelling.

The film does have a clever conceit: the always marvelous Gena Rowlands plays Marion Post, a professor of philosophy, who sublets an apartment to serve as an office where she can write her latest book. A quirk in the ventilation system allows her to inadvertently eavesdrop on the conversations going on next door. The next apartment is the office of a psychiatrist, who counts among his patients a young pregnant woman, played by Mia Farrow. The young woman discusses at length her sorrowful life and suicidal impulses. Because she identifies with the younger woman's feelings of loneliness and alienation, Marion becomes obsessed with eavesdropping on the sessions and uses the situation as a springboard for reevaluating her own life.

It is significant that just as Allen tells the story from a sterile distance, Marion reviews her life only indirectly, though voice-overs, flashbacks, dreams and even symbolic stage productions. Even her psychoanalysis is conducted through a surrogate, Farrow's character, who is rather obviously named Hope. Much of the interaction with other characters occurs in Marion's mind. And rather predictably, Marion's journey of self discovery is, well, rather predictable. She discovers -- as protagonists in this sort of film always discover -- that her successful career and her well-ordered life are a facade hiding her empty relationships and assorted personal failures. Her life of satisfied accomplishment is meaningless and the trust, love and respect she believes she shares with others are delusions. It's like IT'S A WONDERFUL LIFE in reverse: Just as the angel Clarence acts as George Bailey's conscience to show him how valuable his life has been, Hope acts as Marion's conscience to reveal how empty her life as become.

ANOTHER WOMAN has a counterpart in Allen's 2003 film, ANYTHING ELSE; another film with an obvious doppelganger. The former is about a woman who encounters her younger alter ego and reevaluates her past choices, while the latter is about a young man whose encounters with his older alter ego (played by Woody Allen) effects the choices that will shape his future. The same basic story is approached from opposite directions.

It's dangerous to speculate, but it seems that Allen made ANOTHER WOMAN during a time in his life when he was hugely admired for his accomplishments and he was deeply involved in a relationship with Mia Farrow and her extended family. Certainly Farrow's playing a pregnant woman and Marion's second thoughts over placing career over personal relationships seem to suggest a parallel. By contrast, ANYTHING ELSE, made a decade and a half later, finds Allen's character playing a mentor at a time when he is apparently happily married to a much younger woman, and where his status as a filmmaker is more iconic than in vogue. As such, his surrogate changes from being the central figure to the sadder but wiser voice of experience.

Both films are steeped in regret, but make an effort to end in an upbeat fashion. But while ANOTHER WOMAN is an accomplished, polished work striving for a cool perfection, it is not persuasive in its attempt to inspire us with optimism. ANYTHING ELSE is rambling and unfocused and, well, sloppy, but its optimism is honest and funny. ANOTHER WOMAN is about getting another chance, but there is no reason to believe that anything will really change in Marion's tight, introspective little life.

Did you know

- TriviaWoody Allen is not known for complimenting his actors, saying that the fact that he casts them is proof that he considers them great. However, he has said that the scenes between Gena Rowlands and Gene Hackman, particularly in the flashback of the party, were "electrifying."

- GoofsWhilst it is true that the tune of Gymnopédie No. 1 is played at the beginning of the film, it is not the piano version but rather the orchestral version orchestrated by Debussy. For some unknown reason, Debussy changed the numbers of the Gymnopédies: thus the orchestral version of Gymnopédie No. 3 bears the tune of Gymnopédie No. 1!

- SoundtracksGymnopédie No 1

Music by Erik Satie

Performed by Orchestre de la Société des Concerts du Conservatoire

Conducted by Louis Auriacombe

Courtesy of EMI Pathé-Marconi/Capitol Records Special Markets

- How long is Another Woman?Powered by Alexa

Details

Box office

- Budget

- $10,000,000 (estimated)

- Gross US & Canada

- $1,562,749

- Opening weekend US & Canada

- $75,196

- Oct 16, 1988

- Gross worldwide

- $1,562,749

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content