IMDb RATING

5.5/10

6.8K

YOUR RATING

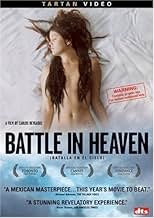

Marcos lusts after his boss's promiscuous daughter, but after botching an extortion scheme, he becomes wracked with guilt.Marcos lusts after his boss's promiscuous daughter, but after botching an extortion scheme, he becomes wracked with guilt.Marcos lusts after his boss's promiscuous daughter, but after botching an extortion scheme, he becomes wracked with guilt.

- Awards

- 1 win & 3 nominations total

- Director

- Writer

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

Featured reviews

Carlos Reygadas's Battle in Heaven (2005), now meticulously restored in 4K, remains a challenging and divisive watch-achingly slow, visually unforgiving, and emotionally desolate. Screened at the Hong Kong Film Archive as part of the Hong Kong Film Critics Society's "Turn of the Century" retrospective, the film resists easy analysis, nor does it offer comfortable spectatorship. It is clearly not for the faint hearted, or those of short-attention spans. There is always a multiplex nearby promoting a Big Loud Action Movie for one to Marvel at whenever we need to detox our senses - this is not that kind of film!

Introduced via video by Mexican film scholar Dr. Salvador Velasco and curated locally by Dr. Derek Lam (a familiar figure across cinematic arts, institutions, and education including HKU), this was cinema as confrontation.

Reygadas famously cast his real-life driver in the lead role, a non-actor inhabiting the body and silence of a man adrift in the moral fog of urban Mexico. Is this gesture inclusive-offering visibility to the often invisible-or is it a stylized form of exploitation, the director manipulating marginality for arthouse credibility? Although the tension hangs heavy throughout to dismiss it would be purile.

Marcos (Marcos Hernández), as the chauffeur, plods his way through the minimal plot, making his understated performance achingly all the more real and unaffected. Neither actor nor director needs to dramatize the pain of name-calling or overly stylize the moment when Marcos's glasses are crushed by careless and callous bystanders on the subway; a slow shift from soft focus to sharpness quietly reminds us of his diminished perspective.

Ana (Anapola Mushkadiz) portrays the general's daughter. She inexplicably works as a sex worker by choice. Reygadas feels no need to formally or narratively offer a dénouement of such a "choice," but nonetheless reveals the precariousness and danger of her position. Bertha Ruiz, as Marcos's wife-a quiet but emotionally resonant presence-is complicit in the film's central tragedy. She somatically encompasses the weight of Marcos's dilemma, hinting at a fractured personality but also an indivisible bond.

These two women-Ana and Marcos's wife-form the emotional and symbolic poles of the film: Ana as a figure of transgressive agency and class tension, and the wife as a vessel of shared guilt and muted grief. Their performances, though understated, are crucial to the film's affective architecture.

There are no Hollywood touch-ups here: the sex scenes are raw to the point of discomfort-not because they're salacious, but because they are unflinchingly real. Reygadas's camera doesn't just linger; it orbits, performs slow, 360-degree pans that flatten the boundary between eroticism and existential numbness. Against a backdrop of greying skies, cracked façades, and tired boulevards, bodies become architectural-burdened, imperfect, defiantly unretouched.

One can't help but ask: is the scene more obscene because these are not idealized bodies? Are we more unsettled by realism than by the stylized falseness of mainstream eroticism or even low-budget pornography? The film seems to argue that truth is more disturbing than fantasy-especially when truth doesn't redeem, explain, or resolve.

There is no catharsis, no tidy emotional arc, no absolution. Battle in Heaven offers instead a daily grind of humiliation and endurance, punctuated by moments so still and sparse they nearly shatter. Is it in those rare flickers of tenderness that the film reveals its pulse-beating not loudly, but stubbornly, beneath the numb exterior, or is this also an enactment?

In their recorded conversation, Dr. Lam and Dr. Velasco articulate the film's enduring relevance-not only as a portrait of a man, but of a city. Battle in Heaven is also a portrait of Mexico City, where, as Velasco notes, "nothing has really changed." The chasm between rich and poor remains as stark as ever. One still passes the greying slums surrounding Benito Juárez Airport before reaching the protected sanctuaries of tree-lined suburbs like Polanco or Coyoacán. The symbolic tension between church and state is etched into the very architecture of the Zócalo, Mexico City's main square-where the Catedral Metropolitana de la Asunción de la Santísima Virgen María a los cielos faces off with the Palacio Nacional, seat of federal power. Santísima Virgen María in an eternal face-off with la Bandera de México.

While the three most internationally celebrated Mexican directors of the 21st century-Guillermo del Toro, Alfonso Cuarón, and Alejandro González Iñárritu-have found their way into living rooms, global streaming platforms, and Academy Award ceremonies, it is Carlos Reygadas's more rarified work-composed of sparse dialogue, long takes, and spiritual unease-that leaves the strongest and most unflinching images in the afterburn of our cinematic retinas.

Battle in Heaven doesn't ask for admiration. It dares you to endure-and then sit with what remains.

Introduced via video by Mexican film scholar Dr. Salvador Velasco and curated locally by Dr. Derek Lam (a familiar figure across cinematic arts, institutions, and education including HKU), this was cinema as confrontation.

Reygadas famously cast his real-life driver in the lead role, a non-actor inhabiting the body and silence of a man adrift in the moral fog of urban Mexico. Is this gesture inclusive-offering visibility to the often invisible-or is it a stylized form of exploitation, the director manipulating marginality for arthouse credibility? Although the tension hangs heavy throughout to dismiss it would be purile.

Marcos (Marcos Hernández), as the chauffeur, plods his way through the minimal plot, making his understated performance achingly all the more real and unaffected. Neither actor nor director needs to dramatize the pain of name-calling or overly stylize the moment when Marcos's glasses are crushed by careless and callous bystanders on the subway; a slow shift from soft focus to sharpness quietly reminds us of his diminished perspective.

Ana (Anapola Mushkadiz) portrays the general's daughter. She inexplicably works as a sex worker by choice. Reygadas feels no need to formally or narratively offer a dénouement of such a "choice," but nonetheless reveals the precariousness and danger of her position. Bertha Ruiz, as Marcos's wife-a quiet but emotionally resonant presence-is complicit in the film's central tragedy. She somatically encompasses the weight of Marcos's dilemma, hinting at a fractured personality but also an indivisible bond.

These two women-Ana and Marcos's wife-form the emotional and symbolic poles of the film: Ana as a figure of transgressive agency and class tension, and the wife as a vessel of shared guilt and muted grief. Their performances, though understated, are crucial to the film's affective architecture.

There are no Hollywood touch-ups here: the sex scenes are raw to the point of discomfort-not because they're salacious, but because they are unflinchingly real. Reygadas's camera doesn't just linger; it orbits, performs slow, 360-degree pans that flatten the boundary between eroticism and existential numbness. Against a backdrop of greying skies, cracked façades, and tired boulevards, bodies become architectural-burdened, imperfect, defiantly unretouched.

One can't help but ask: is the scene more obscene because these are not idealized bodies? Are we more unsettled by realism than by the stylized falseness of mainstream eroticism or even low-budget pornography? The film seems to argue that truth is more disturbing than fantasy-especially when truth doesn't redeem, explain, or resolve.

There is no catharsis, no tidy emotional arc, no absolution. Battle in Heaven offers instead a daily grind of humiliation and endurance, punctuated by moments so still and sparse they nearly shatter. Is it in those rare flickers of tenderness that the film reveals its pulse-beating not loudly, but stubbornly, beneath the numb exterior, or is this also an enactment?

In their recorded conversation, Dr. Lam and Dr. Velasco articulate the film's enduring relevance-not only as a portrait of a man, but of a city. Battle in Heaven is also a portrait of Mexico City, where, as Velasco notes, "nothing has really changed." The chasm between rich and poor remains as stark as ever. One still passes the greying slums surrounding Benito Juárez Airport before reaching the protected sanctuaries of tree-lined suburbs like Polanco or Coyoacán. The symbolic tension between church and state is etched into the very architecture of the Zócalo, Mexico City's main square-where the Catedral Metropolitana de la Asunción de la Santísima Virgen María a los cielos faces off with the Palacio Nacional, seat of federal power. Santísima Virgen María in an eternal face-off with la Bandera de México.

While the three most internationally celebrated Mexican directors of the 21st century-Guillermo del Toro, Alfonso Cuarón, and Alejandro González Iñárritu-have found their way into living rooms, global streaming platforms, and Academy Award ceremonies, it is Carlos Reygadas's more rarified work-composed of sparse dialogue, long takes, and spiritual unease-that leaves the strongest and most unflinching images in the afterburn of our cinematic retinas.

Battle in Heaven doesn't ask for admiration. It dares you to endure-and then sit with what remains.

This film is about a man and wife, who kidnapped a friend's baby for ransom. However, the baby died, and they have to live with the consequences.

The plot outline describes a promising start of an emotional drama. It could have been a captivating story if it was elaborated well. However, the plot ends there. The filmmakers ran out of ideas of what to do, and hence film a car driving around the city for minutes, or film the urban apartment blocks from a rooftop. Or throw in some sex scenes to keep viewers interested.

There is almost no portrayal of Ana and Marco's states of mind after the kidnapping goes wrong. There is no description of the victim's family's grief. Instead, the film wanders around aimlessly and pointlessly. It fails to engage, captivate or evoke any emotions. "Battle in Heaven" describes no battles. It lacks any redeeming value, and I strongly suggest staying away from it.

The plot outline describes a promising start of an emotional drama. It could have been a captivating story if it was elaborated well. However, the plot ends there. The filmmakers ran out of ideas of what to do, and hence film a car driving around the city for minutes, or film the urban apartment blocks from a rooftop. Or throw in some sex scenes to keep viewers interested.

There is almost no portrayal of Ana and Marco's states of mind after the kidnapping goes wrong. There is no description of the victim's family's grief. Instead, the film wanders around aimlessly and pointlessly. It fails to engage, captivate or evoke any emotions. "Battle in Heaven" describes no battles. It lacks any redeeming value, and I strongly suggest staying away from it.

As the director probably hoped, the opening and closing blow job scenes gained this film a great deal of notoriety and attention that far exceeded the publicity such a turgid, self-consciously 'arty' film would normally receive. This unrelentingly ugly and frequently agonisingly boring film is about a couple of days in the life of a man who shags his bosses daughter and who, with his wife, has kidnapped a child (for no explained reason). At times this has the artless artiness of such trash auteurs as Doris Wishman, but give me Doris' 'Deadly Weapons' over this tedious trash any day! Pretentious and dull this is a pastiche of art house world cinema and does not warrant your time

This not an easy picture. It requires Patience and commitment. It's a poetic movie about the urban heaven. About real people. About love and about madness. Reygadas is truly an author. He turns a conventional history in to a great ride through emotions, feelings and in to the overwhelming city of Mexico. Either you love it or hate it, no one comes out of the theater without a comment or a reaction. The movie has the power to move you in a positive or in a negative way. And i guess that something to be thankful about. Mexican films, in recent years, are mostly easy going urban comedies. This totally different. A prove that we can make different stories that reflect the sometimes surreal life of our country. This is one of them. With no professional actors, the movie feels honest and. The cast it's in a very natural level. The Sex scenes are not as important as they seem. Sex is finally a part o who we are, and we are use to see great bodies making love on the screen. It's not easy to see real people doing it, because we may see ourselves in them. And when someone throws your reality at your face, you can hate it. But Batalla En el Cielo does that and even more: Takes that reality to another lever and turns it in to poetry. And that it's just fantastic.

For two thirds of this film I was spellbound and then it suddenly span away from me. Listening to the director speaking afterwards, I think I know what went wrong and I shall have to view again some time to find out. It is all very watchable but slightly confusing towards the end, which is a shame and may be my fault, that of the director or even of Mexico itself. Whilst I have never been to the country it did seem that part of the lifeblood of this movie was the tangled city of contradictions itself. Even though not perfect in my eyes there was enough to show that this is a director of keen and original talent who will produce much more. His liking to work with non actors is welcome and his treatment of actual graphic sex is stunning. Very affecting, bitter sweet movie.

Did you know

- TriviaWriter/director Carlos Reygadas shot crowded street scenes in the middle of real crowds. Cameraman Diego Martínez Vignatti sat in a wheelchair and they just pushed him through everyone. Luckily, no one who passed by looked into the camera lens.

- GoofsDuring the scene where Ana and Marcos are making love, as the camera pans out, a crew member's reflection can be seen in the window.

- ConnectionsEdited into Samo je zemlja ispod ovog neba (2009)

- SoundtracksThe Protecting Veil

Written by John Tavener

Naxos Rights International

Chester Music Limited

Premiére Music Group

- How long is Battle in Heaven?Powered by Alexa

Details

Box office

- Budget

- €1,601,792 (estimated)

- Gross US & Canada

- $70,899

- Opening weekend US & Canada

- $20,351

- Feb 19, 2006

- Gross worldwide

- $258,227

- Runtime

- 1h 38m(98 min)

- Color

- Sound mix

- Aspect ratio

- 1.85 : 1

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content