IMDb RATING

7.1/10

2.9K

YOUR RATING

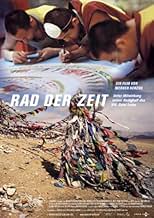

Wheel of Time is Werner Herzog's photographed look at the largest Buddhist ritual in Bodh Gaya, India.Wheel of Time is Werner Herzog's photographed look at the largest Buddhist ritual in Bodh Gaya, India.Wheel of Time is Werner Herzog's photographed look at the largest Buddhist ritual in Bodh Gaya, India.

- Director

- Writer

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

7.12.8K

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Featured reviews

Mandala

In his film My Son, My Son, his protagonist taunts a student meditating on a rock facing a river, telling him to open his eyes, that reality is out there. I was cautious of this, Herzog's encounter not with a simple madness but with an ancient, complex, beautiful point of view, but cautiously optimistic, curious.

We know that Herzog seeks truths in the extremities of life, in the madness that inhabits them. He often guides these subjects to be what he wants them to be, which is his personal reflection that we may find a more eloquent, resilient truth in what deviates rather than what abides, but his visual meditations are tried and true. True enough that Malick, a trobadour himself, has taken from them.

But is he merely a tourist in this, the Kalachakra initiation, a Westerner with a camera strapped around his neck approaching sacred ground with idle curiosity, or does he come in earnest, perhaps to learn?

He shows us the pilgrims travelling the thousands of miles to Bodh Gaya on foot, stopping every couple of steps on this journey that takes as much as three years for one of them, to prostrate themselves on the ground. He says nothing of this but there's no doubt in my mind on why he handpicks them among the crowds. They have a good story of spiritual struggle to tell, perhaps itself a form of holy madness. Elsewhere his camera prowls through a crowd of monks, in the end selectively settling upon the most mysterious face he could find.

There's one moment however in his meeting with the H.H. the 14th Dalai Lama that brilliantly reveals the chasm between these two worlds. Asked about it, the Dalai Lama explains to him what he believes to be the center of the universe, inside of each one of us, doing this with the goodhearted laugh that characterizes him. Mistaking this radiance of equanimity and happiness for an attempt at humour, Herzog quips back that he shouldn't tell his wife about this. The moment follows an awkward pause of silence and a dumbfounded look by the DL.

The above incident, which may reflect badly on him from a formal point but still reflects something, he chose to keep on the film as both a way of undercutting a solemnity he perhaps sees as banal and of showing how far the two cultures are. Herzog may be a stranger here but he's still a talented filmmaker.

And more. The uproar of the pilgrims, how they prepare food and tea for the monks, how they crowd for a good view of the Dalai Lama, he contrasts with the booming silence inside the sanctum, punctured repetitively by the sounds of monks at work on the great sand mandala, the representation of the cosmos.

This is one of the beautiful contrasts of the film. How the superstition of the peasants, who clamor for a crumble of a sacred dumpling thought to be a blessing, with the complex philosophical discussions on concepts of emptiness held openly among the monks elsewhere.

What do the simple folks who came down for this from Nepal understand of shunyata? What do we, in turn, understand of the spiritual importance of performing 100,000 asanas, sun salutations? And what does the Dalai Lama understand of the superstitions he practices in the ceremony, of dropping sticks to see where they may land as pointing into a direction?

Nevertheless, even a man of his own ideas like Herzog leaves this with newfound wisdom, with the potential to enrich us in turn. We get three unforgettable images in the end, all meditatios I will keep inside of me.

How the great sand mandala upon which the Tibetan monks worked tirelessly day and night is eventually destroyed, a palpable reminder of how all things come to pass. The different colored sands brushed aside blend together into abstract shape without pattern or meaning now, to be poured then into the river where after a time they will perhaps wash out in some distant shore.

In Graz, Austria, a security man stands guard in an almost empty hall, guarding nothing from nothing. The self, a barrier to our awareness.

And back again in Bodh Gaya, the ceremony now over, we see the hundreds of thousands of empty pillows left over by the pilgrims lining the floor. In the middle of this emptiness kneels alone one last monk, lost in meditation.

We know that Herzog seeks truths in the extremities of life, in the madness that inhabits them. He often guides these subjects to be what he wants them to be, which is his personal reflection that we may find a more eloquent, resilient truth in what deviates rather than what abides, but his visual meditations are tried and true. True enough that Malick, a trobadour himself, has taken from them.

But is he merely a tourist in this, the Kalachakra initiation, a Westerner with a camera strapped around his neck approaching sacred ground with idle curiosity, or does he come in earnest, perhaps to learn?

He shows us the pilgrims travelling the thousands of miles to Bodh Gaya on foot, stopping every couple of steps on this journey that takes as much as three years for one of them, to prostrate themselves on the ground. He says nothing of this but there's no doubt in my mind on why he handpicks them among the crowds. They have a good story of spiritual struggle to tell, perhaps itself a form of holy madness. Elsewhere his camera prowls through a crowd of monks, in the end selectively settling upon the most mysterious face he could find.

There's one moment however in his meeting with the H.H. the 14th Dalai Lama that brilliantly reveals the chasm between these two worlds. Asked about it, the Dalai Lama explains to him what he believes to be the center of the universe, inside of each one of us, doing this with the goodhearted laugh that characterizes him. Mistaking this radiance of equanimity and happiness for an attempt at humour, Herzog quips back that he shouldn't tell his wife about this. The moment follows an awkward pause of silence and a dumbfounded look by the DL.

The above incident, which may reflect badly on him from a formal point but still reflects something, he chose to keep on the film as both a way of undercutting a solemnity he perhaps sees as banal and of showing how far the two cultures are. Herzog may be a stranger here but he's still a talented filmmaker.

And more. The uproar of the pilgrims, how they prepare food and tea for the monks, how they crowd for a good view of the Dalai Lama, he contrasts with the booming silence inside the sanctum, punctured repetitively by the sounds of monks at work on the great sand mandala, the representation of the cosmos.

This is one of the beautiful contrasts of the film. How the superstition of the peasants, who clamor for a crumble of a sacred dumpling thought to be a blessing, with the complex philosophical discussions on concepts of emptiness held openly among the monks elsewhere.

What do the simple folks who came down for this from Nepal understand of shunyata? What do we, in turn, understand of the spiritual importance of performing 100,000 asanas, sun salutations? And what does the Dalai Lama understand of the superstitions he practices in the ceremony, of dropping sticks to see where they may land as pointing into a direction?

Nevertheless, even a man of his own ideas like Herzog leaves this with newfound wisdom, with the potential to enrich us in turn. We get three unforgettable images in the end, all meditatios I will keep inside of me.

How the great sand mandala upon which the Tibetan monks worked tirelessly day and night is eventually destroyed, a palpable reminder of how all things come to pass. The different colored sands brushed aside blend together into abstract shape without pattern or meaning now, to be poured then into the river where after a time they will perhaps wash out in some distant shore.

In Graz, Austria, a security man stands guard in an almost empty hall, guarding nothing from nothing. The self, a barrier to our awareness.

And back again in Bodh Gaya, the ceremony now over, we see the hundreds of thousands of empty pillows left over by the pilgrims lining the floor. In the middle of this emptiness kneels alone one last monk, lost in meditation.

Perfecting humanity

In 2002 Werner Herzog went to India to observe the festival of Kalachakra, the ritual that takes place every few years to allow Tibetan Buddhist monks to become ordained. An estimated 500,000 Buddhists attended the initiation at Bodh Gaya, the land where the Buddha is believed to have gained enlightenment. The resulting documentary, Wheel of Time, is not a typical Herzog film about manic eccentrics at odds with nature but an often sublime look at an endangered culture whose very way of life is threatened. Herzog admits that he knows little about Buddhism and we do not learn very much about it in the film, yet as we observe the rituals, the celebrations, and the devotion of Tibetan Buddhists we learn much about the richness of their tradition and their strength as a people.

The festival, which lasts ten days, arose out of the desire to create a strong positive bond for inner peace among a large number of people. One notices the almost complete absence of women yet the film ignores it and the narrator makes no comment. The monks begin with chants, music, and mantra recitation to bless the site so that it will be conducive for creating the sand mandala. The magnificently beautiful mandala, which signifies the wheel of time, is carefully constructed at the start of the festival using fourteen different tints of colored sand, then dismantled at the end to dramatize the impermanence of all things. Once built, it is kept in a glass case for the duration of the proceedings so that it will not be disturbed. The most striking aspect of the film are the scenes showing the devotion of the participants.

Using two interpreters, Herzog interviews a monk who took three and one-half years to reach the festival while doing prostrations on the 3000-mile journey. The prostrations, which are similar to bowing and touching the ground, serve as a reminder that we cannot reach enlightenment without first dispelling arrogance and the affliction of pride. In this case, the monk has developed lesions on his hand and a wound on his forehead from touching the earth so many times, yet it hasn't dampened his spirit. Other Buddhists are shown trying to do 100,000 prostrations in six weeks in front of the tree under which the Buddha is supposed to have sat. Herzog introduces a moment of humor when he films a young child imitating the adults by doing his own prostrations but not quite getting the hang of it. In a sequence of rare beauty accompanied by transcendent Tibetan music, we see a Buddhist pilgrimage to worship at the foot of 22,000-foot Mount Kailash, a mountain that is considered in Buddhist and Hindu tradition to be the center of the universe.

The Dalai Lama explains wryly, however, that in reality each of us is truly the center of the universe. After waiting in long lines to witness the Dalai Lama conduct the main ceremony, the crowd is shocked into silence when he tells them that he is too ill to conduct the initiation and will have to wait until the next Kalachakra meeting in Graz, Austria in October. The Graz initiation ceremony is much smaller, however, being confined to a convention hall that can only fit 8000 people; however, everyone is grateful to see the Dalai Lama restored to health. In Austria, Herzog interviews a Tibetan monk who has just been released from a Chinese prison after serving a sentence of thirty-seven years for campaigning for a "Free Tibet". His ecstasy in greeting the Dalai Lama is ineffable. During the closing ceremony, the monks dismantle the Mandala, sweeping up the colored sands and the Dalai Lama releases the mixed sand to the river as a means of extending blessings to the world for peace and healing.

Herzog's mellifluous voice lends a measure of serenity to the proceedings and he seems to be a sympathetic observer. While he makes every effort not to be intrusive, he cannot resist staging a scene toward the end of the film in which a bodyguard is seen presiding over an almost empty convention hall to illustrate the Buddhist concept of emptiness. Wheel of Time may not be Herzog's best work but it does contain moments of grace and images of spectacular beauty. Because of the destruction of their heritage, the Tibetans survive today mainly in the refugee camps of India. Any effort that promotes an understanding of their culture is very welcome and Wheel of Time provides us with an insight into an ancient tradition geared toward perfecting humanity through quieting the mind and cultivating compassion.

The festival, which lasts ten days, arose out of the desire to create a strong positive bond for inner peace among a large number of people. One notices the almost complete absence of women yet the film ignores it and the narrator makes no comment. The monks begin with chants, music, and mantra recitation to bless the site so that it will be conducive for creating the sand mandala. The magnificently beautiful mandala, which signifies the wheel of time, is carefully constructed at the start of the festival using fourteen different tints of colored sand, then dismantled at the end to dramatize the impermanence of all things. Once built, it is kept in a glass case for the duration of the proceedings so that it will not be disturbed. The most striking aspect of the film are the scenes showing the devotion of the participants.

Using two interpreters, Herzog interviews a monk who took three and one-half years to reach the festival while doing prostrations on the 3000-mile journey. The prostrations, which are similar to bowing and touching the ground, serve as a reminder that we cannot reach enlightenment without first dispelling arrogance and the affliction of pride. In this case, the monk has developed lesions on his hand and a wound on his forehead from touching the earth so many times, yet it hasn't dampened his spirit. Other Buddhists are shown trying to do 100,000 prostrations in six weeks in front of the tree under which the Buddha is supposed to have sat. Herzog introduces a moment of humor when he films a young child imitating the adults by doing his own prostrations but not quite getting the hang of it. In a sequence of rare beauty accompanied by transcendent Tibetan music, we see a Buddhist pilgrimage to worship at the foot of 22,000-foot Mount Kailash, a mountain that is considered in Buddhist and Hindu tradition to be the center of the universe.

The Dalai Lama explains wryly, however, that in reality each of us is truly the center of the universe. After waiting in long lines to witness the Dalai Lama conduct the main ceremony, the crowd is shocked into silence when he tells them that he is too ill to conduct the initiation and will have to wait until the next Kalachakra meeting in Graz, Austria in October. The Graz initiation ceremony is much smaller, however, being confined to a convention hall that can only fit 8000 people; however, everyone is grateful to see the Dalai Lama restored to health. In Austria, Herzog interviews a Tibetan monk who has just been released from a Chinese prison after serving a sentence of thirty-seven years for campaigning for a "Free Tibet". His ecstasy in greeting the Dalai Lama is ineffable. During the closing ceremony, the monks dismantle the Mandala, sweeping up the colored sands and the Dalai Lama releases the mixed sand to the river as a means of extending blessings to the world for peace and healing.

Herzog's mellifluous voice lends a measure of serenity to the proceedings and he seems to be a sympathetic observer. While he makes every effort not to be intrusive, he cannot resist staging a scene toward the end of the film in which a bodyguard is seen presiding over an almost empty convention hall to illustrate the Buddhist concept of emptiness. Wheel of Time may not be Herzog's best work but it does contain moments of grace and images of spectacular beauty. Because of the destruction of their heritage, the Tibetans survive today mainly in the refugee camps of India. Any effort that promotes an understanding of their culture is very welcome and Wheel of Time provides us with an insight into an ancient tradition geared toward perfecting humanity through quieting the mind and cultivating compassion.

Grand Tertön

Werner Herzog again.

This time he is in his mode of creation more by discovery than invention, and it pays off.

The raw material is striking by itself: vast numbers, ephemeral yearnings, trivial and essential rituals. Devotion in any endeavor is something we are drawn to, and there is plenty for our filmmaker to harvest.

The essential part of this film is Herzog as camera during a gathering in India, where a variety of consecrations are planned. Monks and devotees come, some by difficult and humbling means. 400,000 faces (all attempting calmness) are miraculously organized, assembled to be led by the supreme priest.

We see queues so orderly they could only exist among such beings, but anxious chaos when fighting for tossed goodies: dumplings and candies. We have zealots, order and peace.

Into this sails Herzog. The story is that he had been cajoled into filming the much smaller gathering in Austria. Austria! He was reluctant to do so, and after the film remains firm in his belief that Austrian Buddhists don't make much sense to him. But with this commitment, he traveled to the gathering in a sacred place in India near Nepal.

There he found a focus for his film in one of the rituals. Though it is presented as central to the gathering, it is only so in Herzog's vision. This holds that mysteries can be conveyed visually. The situation needs to support the vision, but the vision is the thing. It is not the symbol, the notation, the token, but the real thing. This is how he thinks of cinema and the way he presents the sand mandala carries this import.

The "Wheel of Time" is one translation of a sand painting made for this type of gathering, as perfected and maintained by one of the groups in Tibet. Mandalas are movies and intended for meditation, as a structure existing between and shared by the mind of insight and the real world of color and structure. There is much to be said of them and cinema, but Herzog only could film this one (and its copy in Austria) as it is being made with colored sand and exhibited as devotees are rushed past it.

He then went to Mount Kailash, Though this is a couple hundred miles away, he merges it seamlessly into the gathering of nearly half a million robed prayers. Here, he is able to make some magnificent images of the mountain, its waterways and the people ritualistically circumnavigating it. This is holiness he understands and the conflation of mountain and mandala works.

As usual, the music adds great power. I believe that henceforth, I will associate that music with this devotion, though there is no relation other than Herzog chose to build his mandala of these sounds, this extract of natural rock and water, and these people. They would not recognize their devotions as shown here. (And some of this is staged.) But for me, it is a window into something more holy than they worship.

Ted's Evaluation -- 3 of 3: Worth watching.

This time he is in his mode of creation more by discovery than invention, and it pays off.

The raw material is striking by itself: vast numbers, ephemeral yearnings, trivial and essential rituals. Devotion in any endeavor is something we are drawn to, and there is plenty for our filmmaker to harvest.

The essential part of this film is Herzog as camera during a gathering in India, where a variety of consecrations are planned. Monks and devotees come, some by difficult and humbling means. 400,000 faces (all attempting calmness) are miraculously organized, assembled to be led by the supreme priest.

We see queues so orderly they could only exist among such beings, but anxious chaos when fighting for tossed goodies: dumplings and candies. We have zealots, order and peace.

Into this sails Herzog. The story is that he had been cajoled into filming the much smaller gathering in Austria. Austria! He was reluctant to do so, and after the film remains firm in his belief that Austrian Buddhists don't make much sense to him. But with this commitment, he traveled to the gathering in a sacred place in India near Nepal.

There he found a focus for his film in one of the rituals. Though it is presented as central to the gathering, it is only so in Herzog's vision. This holds that mysteries can be conveyed visually. The situation needs to support the vision, but the vision is the thing. It is not the symbol, the notation, the token, but the real thing. This is how he thinks of cinema and the way he presents the sand mandala carries this import.

The "Wheel of Time" is one translation of a sand painting made for this type of gathering, as perfected and maintained by one of the groups in Tibet. Mandalas are movies and intended for meditation, as a structure existing between and shared by the mind of insight and the real world of color and structure. There is much to be said of them and cinema, but Herzog only could film this one (and its copy in Austria) as it is being made with colored sand and exhibited as devotees are rushed past it.

He then went to Mount Kailash, Though this is a couple hundred miles away, he merges it seamlessly into the gathering of nearly half a million robed prayers. Here, he is able to make some magnificent images of the mountain, its waterways and the people ritualistically circumnavigating it. This is holiness he understands and the conflation of mountain and mandala works.

As usual, the music adds great power. I believe that henceforth, I will associate that music with this devotion, though there is no relation other than Herzog chose to build his mandala of these sounds, this extract of natural rock and water, and these people. They would not recognize their devotions as shown here. (And some of this is staged.) But for me, it is a window into something more holy than they worship.

Ted's Evaluation -- 3 of 3: Worth watching.

Excellent Herzog fare; surreal, stylistic, yet real

I just saw Wheel of Time yesterday at its premiere in Toronto, where Herzog was present. As usual, Herzog creates a compelling film: a portrait of a traditional Bhuddist initiation ceremony. Specifically, we are shown the pilgrimmage of hundreds of thousands of people to India and one year later, to a similar ceremony in Austria. On a purely documentary level, this winning film is a fascinating piece, giving insight into this ancient ceremony (including the pilgrimmage itself), as well as showing us the painstaking construction of a large "mandala" made out of colored sand, with a "wheel of time" intricately designed in its center. The interviews with the Dalai Lama were interesting and even humorous. On an artistic level, it is also a winner, as Herzog mixes stylistic poses and environmental landscapes within the structure of the documentary. Of course, Herzog's critics call this self-indulgence, but I strongly disagree. Herzog operates on a subconcious level in most of his films, including his narrative features, and actually succeeds where other "artsy" filmmakers fail miserably. Herzog has produced yet another fascinating masterpiece.

The unexpected calmness of Werner Herzog

`Wheel of Time' is a very good film, but I admit that it is different from what I expected from Herzog. He is still very talented, but I doubt if the subject matter is best suited to him. `Wheel of Time' concerns many things, including religion, virtue, and faith, which in this case may not be the best subjects for Herzog. But when `Wheel of Time' deals with some strange and crazy rituals, political oppression, and rugged landscapes, these parts of the film are very satisfying.

Some scenes in `Wheel of Time' are magical, especially the scenes which show vast landscapes and people performing strange rituals. Those scenes are Herzogian, I think. Nobody does this kind of thing better than Herzog. If a cinephile watches these scenes, not knowing who shot them, he or she will guess correctly that they were shot by Herzog. These scenes make `Wheel of Time' rise way above television documentaries.

But other scenes are not as magical as I expect from Herzog's films. I think that maybe the religious subject matter of this film doesn't allow Herzog to be as playful in directing as he was in other films. It is very difficult for any filmmaker, including Herzog, to make an interesting documentary about something virtuous like this. It would be much easier to make an interesting film if the film is about `good vs. evil', or about some strange rituals in which people walk on fire and pierce themselves horrifically.

I think Herzog is like a wizard, and one can hardly makes a more magical film than him if the film is about nature-made or man-made madness, brutality, or suffering in life. But because of the subject matter of `Wheel of Time', this film is not my most favorite of Herzog's. I like `Wheel of Time' as much as Herzog's `How Much Wood Would a Woodchuck Chuck' (1976) and `The Flying Doctors of East Africa' (1969). I think these three films are very good films, but because the people portrayed in these films are not `very' strange nor `very' crazy, these three films lack some kind of excitement I found in other films by Herzog, especially when compared to Herzog's `Gesualdo: Death for Five Voices' (1995), `My Best Fiend' (1999), `The Great Ecstasy of Woodcarver Steiner' (1974), and `Land of Silence and Darkness' (1971), which is my most favorite of Herzog's films.

Some parts of Herzog's `Lessons of Darkness' (1992) deal with political madness, and I think Herzog is good at this subject, too. In one scene in `Wheel of Time', a former political prisoner gave an interview about the brutality of the Chinese rule. This scene is very simple. It is just a normal interview. But for me the power of this scene is much more stronger than most scenes in `Wheel of Time'. And it also reminds me of some great scenes in `Lessons of Darkness' in which some people gave their own testimonies to what happened when Saddam invaded Kuwait. I think one thing that makes the scene about the former prisoner stand apart from other scenes in `Wheel of Time' is because this scene talks about `evil forces', while other scenes in `Wheel of Time' are about some kind of virtuous power.

Some scenes in `Wheel of Time' are magical, especially the scenes which show vast landscapes and people performing strange rituals. Those scenes are Herzogian, I think. Nobody does this kind of thing better than Herzog. If a cinephile watches these scenes, not knowing who shot them, he or she will guess correctly that they were shot by Herzog. These scenes make `Wheel of Time' rise way above television documentaries.

But other scenes are not as magical as I expect from Herzog's films. I think that maybe the religious subject matter of this film doesn't allow Herzog to be as playful in directing as he was in other films. It is very difficult for any filmmaker, including Herzog, to make an interesting documentary about something virtuous like this. It would be much easier to make an interesting film if the film is about `good vs. evil', or about some strange rituals in which people walk on fire and pierce themselves horrifically.

I think Herzog is like a wizard, and one can hardly makes a more magical film than him if the film is about nature-made or man-made madness, brutality, or suffering in life. But because of the subject matter of `Wheel of Time', this film is not my most favorite of Herzog's. I like `Wheel of Time' as much as Herzog's `How Much Wood Would a Woodchuck Chuck' (1976) and `The Flying Doctors of East Africa' (1969). I think these three films are very good films, but because the people portrayed in these films are not `very' strange nor `very' crazy, these three films lack some kind of excitement I found in other films by Herzog, especially when compared to Herzog's `Gesualdo: Death for Five Voices' (1995), `My Best Fiend' (1999), `The Great Ecstasy of Woodcarver Steiner' (1974), and `Land of Silence and Darkness' (1971), which is my most favorite of Herzog's films.

Some parts of Herzog's `Lessons of Darkness' (1992) deal with political madness, and I think Herzog is good at this subject, too. In one scene in `Wheel of Time', a former political prisoner gave an interview about the brutality of the Chinese rule. This scene is very simple. It is just a normal interview. But for me the power of this scene is much more stronger than most scenes in `Wheel of Time'. And it also reminds me of some great scenes in `Lessons of Darkness' in which some people gave their own testimonies to what happened when Saddam invaded Kuwait. I think one thing that makes the scene about the former prisoner stand apart from other scenes in `Wheel of Time' is because this scene talks about `evil forces', while other scenes in `Wheel of Time' are about some kind of virtuous power.

Did you know

- Quotes

The Dalai Lama: All religions carry same message. Message of love, compassion, forgiveness, tolerance, contentment, self-discipline. I think we need these qualities, irrespective of whether we are believer or non-believer, because these are the source of a happy life.

- SoundtracksHimal

Performed by Prem Rama Autari

- How long is Wheel of Time?Powered by Alexa

Details

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content