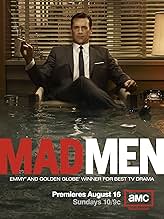

The Gypsy and the Hobo

- Episode aired Oct 25, 2009

- TV-14

- 1h

IMDb RATING

9.2/10

3.8K

YOUR RATING

An old flame and potential client reenters Roger Sterling's life, Joan's husband searches for a new job, and Don finally comes clean to Betty about his true identity.An old flame and potential client reenters Roger Sterling's life, Joan's husband searches for a new job, and Don finally comes clean to Betty about his true identity.An old flame and potential client reenters Roger Sterling's life, Joan's husband searches for a new job, and Don finally comes clean to Betty about his true identity.

Vincent Kartheiser

- Pete Campbell

- (credit only)

Bryan Batt

- Salvatore Romano

- (credit only)

Michael Gladis

- Paul Kinsey

- (credit only)

Aaron Staton

- Ken Cosgrove

- (credit only)

Rich Sommer

- Harry Crane

- (credit only)

9.23.8K

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Featured reviews

The most devastatiing episode, culminating in the inevitable, terrifying confrontation between Don and Betty Draper over his identity

"The Gypsy and the Hobo," the eleventh episode of Mad Men's third season, directed by Jennifer Getzinger is perhaps the most intensely focused and emotionally devastating episode of the series up to this point, culminating in the inevitable, terrifying confrontation between Don and Betty Draper over his identity. The title refers to the Halloween costumes worn by Don and Betty's children, Sally and Bobby, which perfectly metaphorize the Drapers' marriage: Betty is the "Gypsy," a wanderer who is seeking freedom and escaping her roots, while Don is the "Hobo," a rootless impostor constantly moving to avoid detection. The atmosphere of Halloween-a night of masquerade and the peeling back of facades-provides the perfect backdrop for the unmasking of Don Draper. The narrative is a continuous build of domestic tension, where Betty's silent knowledge from "The Color Blue" finally explodes, forcing Don to reveal the truth of Dick Whitman and the theft of his identity. Getzinger's direction is marked by a deep sense of psychological claustrophobia, using tight framing and lingering silences to convey the profound discomfort and trauma of the long-awaited confession.

The central, pivotal sequence is the confrontation between Don and Betty, triggered by Betty's discovery of the identity box in the previous episode. Having armed herself with the truth, Betty orchestrates a chilling, controlled confrontation. Don, stripped of his usual defenses and exhausted by the effort of maintaining the facade, is finally forced to confess the complete story of Dick Whitman and the death of the real Don Draper in Korea. This moment is a culmination of three seasons of narrative suspense and psychological buildup. Jon Hamm delivers a masterful performance, conveying Don's vulnerability and shame through controlled, halting language, making the confession feel like an emotional excavation. Betty's reaction, equally compellingly portrayed by January Jones, is not one of explosive anger, but of cold, calculating revulsion. The truth gives her the ultimate power and emotional leverage to finally end the marriage on her own terms, confirming that the identity fraud is a deeper, more profound betrayal than the sexual infidelity.

Don's confession, revealed over the course of the episode, is the most extensive and explicit account of his origins since the Season Two finale. We learn about his time in Korea, the accidental death of the original Don Draper, and the decision to switch dog tags to desert the war and erase his own painful past. The narrative positions the Don Draper persona as a desperate act of existential self-preservation, born from a traumatic childhood and military desertion. This act of identity theft, however, becomes the original sin that haunts his entire life, making every subsequent success and relationship fraudulent. The theme of war and its emotional scars is central; Don is a psychological casualty of the Korean conflict, his escape from the battlefield merely trading one kind of fight for another-the constant, exhausting battle to maintain his lie. The emotional climax of the confession is not the details of the past, but the painful recognition of the present: the fact that Don's entire adult life with Betty has been a lie.

The professional plot involves Peggy Olson being caught in a moral and professional bind, mirroring the ethical costs of survival at Sterling Cooper. Pete Campbell, desperate to avoid working with Don, tries to recruit Peggy to join him at another agency. Peggy, faced with the opportunity for guaranteed professional advancement and more money, is forced to confront her loyalty to Don-the man who, despite his flaws, first recognized her talent.

Simultaneously, she is drawn into a professional relationship with Duck Phillips, who continues to exploit their romantic history to try and lure her (and Don) to his agency. Peggy's storyline centers on the price of ambition and the necessity of professional secrecy. Her decision to ultimately remain at Sterling Cooper, despite the allure of a new beginning, signals her commitment to meritocratic achievement over easy professional escape, but it also forces her to remain complicit in the agency's (and Don's) moral murkiness.

The immediate aftermath of the confession focuses on Betty's calculated move toward divorce. The final confrontation leaves her emotionally exhausted but professionally empowered; the truth of Dick Whitman gives her the ultimate justification she needs to end the marriage and pursue Henry Francis. The use of the children's Halloween costumes-Sally and Bobby wandering the neighborhood in their masks-is a tragic metaphor for their vulnerability. They are unwitting casualties of their parents' disintegrating marriage and Don's secret past, foreshadowing the complex psychological issues that will define them later in the series. The episode highlights the cycle of emotional inheritance; just as Don's childhood trauma dictated his adult life, the Drapers' marital decay will inevitably scar their children, trapping them in the consequences of their parents' choices.

Jennifer Getzinger's direction is key to the episode's success, transforming the suburban home into a psychological pressure cooker. The camera often lingers on January Jones's face, capturing Betty's tightly controlled rage and shock in silent close-ups. The atmosphere of Halloween night-the spooky, slightly off-kilter energy of the holiday-permeates the episode, emphasizing the blurring of reality and performance. The use of the Draper children in their masks further underscores the central theme of hidden identities. The confrontation scene is visually minimalist, relying almost entirely on the actors' performances and the oppressive silence in the room to communicate the magnitude of the revelation, lending the episode a theatrical, chamber-piece quality.

"The Gypsy and the Hobo" is a monumental episode that achieves the difficult task of making a three-season-long reveal feel earned, traumatic, and wholly necessary. The creators' primary message is that truth is a destructive, but ultimately necessary, force. Don Draper's lifelong attempt to cheat fate through the theft of an identity is finally undone, not by an external enemy, but by the quiet, internal decay of his own marriage. The episode closes the door on the domestic stability of the Drapers, confirming that the foundation of their life was built on sand. The final, sober message is that while the lie of Dick Whitman provided Don with a professional escape, it simultaneously built a personal cage, and only its violent destruction can offer the possibility of an authentic, though terrifyingly uncertain, future.

The central, pivotal sequence is the confrontation between Don and Betty, triggered by Betty's discovery of the identity box in the previous episode. Having armed herself with the truth, Betty orchestrates a chilling, controlled confrontation. Don, stripped of his usual defenses and exhausted by the effort of maintaining the facade, is finally forced to confess the complete story of Dick Whitman and the death of the real Don Draper in Korea. This moment is a culmination of three seasons of narrative suspense and psychological buildup. Jon Hamm delivers a masterful performance, conveying Don's vulnerability and shame through controlled, halting language, making the confession feel like an emotional excavation. Betty's reaction, equally compellingly portrayed by January Jones, is not one of explosive anger, but of cold, calculating revulsion. The truth gives her the ultimate power and emotional leverage to finally end the marriage on her own terms, confirming that the identity fraud is a deeper, more profound betrayal than the sexual infidelity.

Don's confession, revealed over the course of the episode, is the most extensive and explicit account of his origins since the Season Two finale. We learn about his time in Korea, the accidental death of the original Don Draper, and the decision to switch dog tags to desert the war and erase his own painful past. The narrative positions the Don Draper persona as a desperate act of existential self-preservation, born from a traumatic childhood and military desertion. This act of identity theft, however, becomes the original sin that haunts his entire life, making every subsequent success and relationship fraudulent. The theme of war and its emotional scars is central; Don is a psychological casualty of the Korean conflict, his escape from the battlefield merely trading one kind of fight for another-the constant, exhausting battle to maintain his lie. The emotional climax of the confession is not the details of the past, but the painful recognition of the present: the fact that Don's entire adult life with Betty has been a lie.

The professional plot involves Peggy Olson being caught in a moral and professional bind, mirroring the ethical costs of survival at Sterling Cooper. Pete Campbell, desperate to avoid working with Don, tries to recruit Peggy to join him at another agency. Peggy, faced with the opportunity for guaranteed professional advancement and more money, is forced to confront her loyalty to Don-the man who, despite his flaws, first recognized her talent.

Simultaneously, she is drawn into a professional relationship with Duck Phillips, who continues to exploit their romantic history to try and lure her (and Don) to his agency. Peggy's storyline centers on the price of ambition and the necessity of professional secrecy. Her decision to ultimately remain at Sterling Cooper, despite the allure of a new beginning, signals her commitment to meritocratic achievement over easy professional escape, but it also forces her to remain complicit in the agency's (and Don's) moral murkiness.

The immediate aftermath of the confession focuses on Betty's calculated move toward divorce. The final confrontation leaves her emotionally exhausted but professionally empowered; the truth of Dick Whitman gives her the ultimate justification she needs to end the marriage and pursue Henry Francis. The use of the children's Halloween costumes-Sally and Bobby wandering the neighborhood in their masks-is a tragic metaphor for their vulnerability. They are unwitting casualties of their parents' disintegrating marriage and Don's secret past, foreshadowing the complex psychological issues that will define them later in the series. The episode highlights the cycle of emotional inheritance; just as Don's childhood trauma dictated his adult life, the Drapers' marital decay will inevitably scar their children, trapping them in the consequences of their parents' choices.

Jennifer Getzinger's direction is key to the episode's success, transforming the suburban home into a psychological pressure cooker. The camera often lingers on January Jones's face, capturing Betty's tightly controlled rage and shock in silent close-ups. The atmosphere of Halloween night-the spooky, slightly off-kilter energy of the holiday-permeates the episode, emphasizing the blurring of reality and performance. The use of the Draper children in their masks further underscores the central theme of hidden identities. The confrontation scene is visually minimalist, relying almost entirely on the actors' performances and the oppressive silence in the room to communicate the magnitude of the revelation, lending the episode a theatrical, chamber-piece quality.

"The Gypsy and the Hobo" is a monumental episode that achieves the difficult task of making a three-season-long reveal feel earned, traumatic, and wholly necessary. The creators' primary message is that truth is a destructive, but ultimately necessary, force. Don Draper's lifelong attempt to cheat fate through the theft of an identity is finally undone, not by an external enemy, but by the quiet, internal decay of his own marriage. The episode closes the door on the domestic stability of the Drapers, confirming that the foundation of their life was built on sand. The final, sober message is that while the lie of Dick Whitman provided Don with a professional escape, it simultaneously built a personal cage, and only its violent destruction can offer the possibility of an authentic, though terrifyingly uncertain, future.

For History's Sake

Great episode, and of course, great ending, and last line, although this one's far better when you see it the first time then re-watching, after knowing everything, and it gets a bit long...

Which does NOT mean that originally there's anything wrong with the pacing of Don telling Betty about his past, but still... this one's highly rated for the history of the series more than anything else...

There's not a whole lot going on otherwise, and the most annoying character is given way too much screen-time, and that's Joan's rapist husband, who looks like he's got Kodiak packed under his bottom lip, and I keeping waiting for him to spit...

Anyhow, another classic episode on a classic show.

Which does NOT mean that originally there's anything wrong with the pacing of Don telling Betty about his past, but still... this one's highly rated for the history of the series more than anything else...

There's not a whole lot going on otherwise, and the most annoying character is given way too much screen-time, and that's Joan's rapist husband, who looks like he's got Kodiak packed under his bottom lip, and I keeping waiting for him to spit...

Anyhow, another classic episode on a classic show.

And who are you supposed to be?

That question is the one we have been asking ourselves and finally we get to know because all the secrets has been revealed, and i am not going to spoil it out you all watch and enjoy, so much feelings.

Did you know

- TriviaBert: The Misfits, the movie, Clark Gable, it was about horses being turned into dog food. The Misfits was a movie that came out in 1961 which was the last movie for both of the leading stars, Clark Gable and Marilyn Monroe. It tells the story of an aging ex-cowboy prone to gambling and surviving on mustang rustling. He sells the horses to slaughterhouses for the manufacture of dog food.

- GoofsIn the scene where Betty is in Don's study as she slumps into his chair you can see some of the book titles on the shelf behind her. One of the books is a book club edition collection of the first three books in "The Corps" series by W.E.B. Griffin. The first book in the series wasn't published until 1986, 23 years after this episode takes place.

- Quotes

Betty Draper: What would you do if you were me? Would you love you?

Don Draper: I was surprised that you ever loved me.

- ConnectionsFeatured in The 62nd Primetime Emmy Awards (2010)

Details

- Release date

- Country of origin

- Official sites

- Language

- Filming locations

- Production companies

- See more company credits at IMDbPro

- Runtime

- 1h(60 min)

- Color

- Sound mix

- Aspect ratio

- 1.78 : 1

- 16:9 HD

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content