American director Andy Milligan is best known on the cult circuit for the numerous trashy exploitation movies he put out during the 1960s and 70s, namely the likes of Bloodthirsty Butchers (1970), The Rats Are Coming! The Werewolves Are Here! (1972) and, most famously, the video nasty The Ghastly Ones (1968). His work isn't fondly remembered, and his horror pictures are perhaps only worthwhile for their unintentional comedic value. However, Milligan occasionally dabbled in art-house movies, and Nightbirds - made in Britain - is one of the most interesting, if plodding, things he's ever done. Thought lost for years, the combined efforts of Nicolas Winding Refn and the BFI have allowed the film to be pieced back together and re- released after decades in the wilderness.

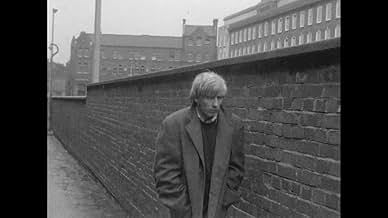

On the grainy streets of late 60s London, a young homeless man named Dink (Berwick Kaler) is discovered puking his guts up by the striking Dee (Julie Shaw), who takes the hapless mummy's boy back to her decaying flat. While Dink is clearly socially inept and inexperienced with women thanks to years of mental abuse at the hands of his overbearing mother, he strikes up an intensely sexual relationship with Dee. The good times soon give way to jealousy however, as Dee disapproves of any woman Dink strikes up a conversation with, and Dink becoming increasingly frustrated at the frequent presence of Dee's creepy Irish neighbour. As they gradually attempt to control one another, the once blissful and sexually- charged relationship turns to cruelty and bitterness.

It barely saw the inside of a cinema screen during its release back in 1970, and its somewhat difficult to see how it will find an audience all these years later. It's a deliberately provocative piece, full of sexual imagery and foul language, but it's also incredibly slow- moving, even at a measly 74 minutes. While Kaler does well as the timid, neurotic Dink (who went on to have a successful career on British TV), Shaw struggles to emote much at all. Her character is manipulative and sexually dominant, and calls for a performance capable of handling such complexities, but Shaw barely manages to convincingly switch between happy and sad. Still, it's a nice change of pace from the usual free-loving and swinging 60s the movies usually inform us it was, and suggests that there was a little bit more to Milligan than the schlocky output he was best known for.