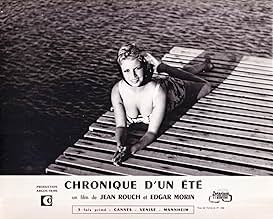

Chronique d'un été (Paris 1960)

- 1961

- Tous publics

- 1h 25min

NOTE IMDb

7,5/10

3,7 k

MA NOTE

Documentaire sur la vie quotidienne de Parisiens ordinaires, réalisé dans le style cinéma-vérité.Documentaire sur la vie quotidienne de Parisiens ordinaires, réalisé dans le style cinéma-vérité.Documentaire sur la vie quotidienne de Parisiens ordinaires, réalisé dans le style cinéma-vérité.

- Récompenses

- 1 victoire au total

Marceline Loridan Ivens

- Self

- (as Marceline)

Marilù Parolini

- Self

- (as Mary Lou)

Jean-Pierre Sergent

- Self

- (as Jean-Pierre)

Jacques Gautrat

- Self - un ouvrier

- (as Jacques)

Régis Debray

- Self - un étudiant

- (as Régis)

Nadine Ballot

- Self

- (as Nadine)

Modeste Landry

- Self - un étudiant africain

- (as Landry)

Jacques Gabillon

- Self - un employé

- (as Jacques)

Simone Gabillon

- Self - une employée

- (as Simone)

Histoire

Le saviez-vous

- AnecdotesThe 6th greatest documentary of all time according to the 'Sight & Sound' poll 2014. The list was compiled after polling from over 200 critics and curators and 100 filmmakers.

- Citations

Sophie - the cover-girl: People are bored everywhere now. But boredom comes from within. If you've got an inner life, you're never bored.

- ConnexionsFeatured in Les échos du cinéma: Épisode #1.23 (1961)

Commentaire à la une

Dugan McShain Anthropological Film Chronicle of a summer Chronique d'un été

Filmmaker Jean Rouch, in coordination with sociologist Edgar Morin, create a story out of seemingly random interviews and anecdotes. Together they create a piece that describes life in Paris circa 1961, they converse with their friends and associates about life, the current war in Algeria, and the mindset of the daily life of Parisians. Using the newly available 16mm camera they set out to do what no one had done before them: try and capture daily life and discuss it. They talk at length about politics, arguing on film, and discuss, both during the film and at the end when the filmmakers show their finished work to the participants and have them dissect it.

They give feedback, feelings and talk about the characters, describing what worked and didn't, what felt real and what seemed contrived. The people that they interview are across the board when looked at socioeconomically, intellectually, and racially, providing alternate views about the problems faced, the stories that they needed to tell to the camera and the trials that were associated with their lives.

I was, to say the least disappointed with the final product that was shown. As I was watching the film there came a scene where the two filmmakers are discussing their participation and the feat that they had just accomplished with the finished film ready to be shown. It was a very intimate scene where it seemed as if both of the filmmakers were unaware that they were being filmed and as such proceeded to expound on the principles, and the theory of making an anthropological film.

It was half way through this conversation that I realized that they staged this discussion not as a candid frank debate but as a 'realistic end cap' to put on their film to add flair and realism. What seemed at first as a novel approach to film-making came off more as a clever marketing ploy, using the audience as a sounding board, and bringing the audience closer to the subject matter of the film through the use of intimacy.

The filmmakers opted for participation in the film instead of the typical vein of anonymity. Reflexivity is a device that is used to vary the distance from a subject, giving the idea that the filmmakers, the product and everything that goes along with it a unity in the production. This style is self-serving in that the filmmakers could be seen prompting the subjects and providing a direct line of questions that they could use to form a solid piece. In the court of law this is called 'leading the witness' in order to get the desired answers that you seek, as opposed to the answers that come naturally from a subject matter that is brought up.

Rouch gives specific questions that lend themselves to specific answers. "I would argue that most anthropologists implicitly believe content should so dominate form in scientific writing that the form and style of an ethnography appears to "naturally" flow out from the content." - (Ruby, Studies in the anthropology of Visual Communication, Pg 106,Vol. 2, No. 2, Fall 1975). In providing specific questions, they do not let the life naturally 'flow' but instead impede it at their own will destroying the illusion that they have created. These filmmakers seem almost like they wish to participate in the very spectacle they wish to show, and cannot distance themselves from the subjects for fear of losing notoriety.

Morin and Rouch are extremely open to their subjects, providing valuable insight into their minds, as well as the minds of the people whom they are interviewing. This certainly provides for honesty in front of the camera creating a cushion of comfort for the subjects so that the camera does not seem to interfere as much a simply record. In certain scenes it seemed as if we were an observer regarding these people with a cold unfeeling eye. The argument in the hallway for example. This does not lend itself to a self-conscious conversation.

There are moments in the film that do seem very contrived however. There is a scene of a woman walking through the streets of Paris along with her walking we hear her telling the story of her father's internment and her own in a Nazi death camp. This is obviously a scripted scene. It lends itself to disbelief when we see that she is walking, lost in thought. The technique of us hearing those thoughts is vital to this disbelief.

The film-making was excellent at times, as I said, giving the sensation of an omniscient- floating eyeball, observing the people at their daily lives. This feeling is ruined however when we are privy to the Rouch's and Morin's conversation on what they feel the outcome of the film represents. It creates a feeling of false voyeurism then, incompatible with the sensitive proximity that we have just watched. The scene in the theater when he shows the characters dissecting each other is especially grating as it lends it self even more to a Dali-esquire surrealism where the characters are watching themselves as we watch them.

Filmmaker Jean Rouch, in coordination with sociologist Edgar Morin, create a story out of seemingly random interviews and anecdotes. Together they create a piece that describes life in Paris circa 1961, they converse with their friends and associates about life, the current war in Algeria, and the mindset of the daily life of Parisians. Using the newly available 16mm camera they set out to do what no one had done before them: try and capture daily life and discuss it. They talk at length about politics, arguing on film, and discuss, both during the film and at the end when the filmmakers show their finished work to the participants and have them dissect it.

They give feedback, feelings and talk about the characters, describing what worked and didn't, what felt real and what seemed contrived. The people that they interview are across the board when looked at socioeconomically, intellectually, and racially, providing alternate views about the problems faced, the stories that they needed to tell to the camera and the trials that were associated with their lives.

I was, to say the least disappointed with the final product that was shown. As I was watching the film there came a scene where the two filmmakers are discussing their participation and the feat that they had just accomplished with the finished film ready to be shown. It was a very intimate scene where it seemed as if both of the filmmakers were unaware that they were being filmed and as such proceeded to expound on the principles, and the theory of making an anthropological film.

It was half way through this conversation that I realized that they staged this discussion not as a candid frank debate but as a 'realistic end cap' to put on their film to add flair and realism. What seemed at first as a novel approach to film-making came off more as a clever marketing ploy, using the audience as a sounding board, and bringing the audience closer to the subject matter of the film through the use of intimacy.

The filmmakers opted for participation in the film instead of the typical vein of anonymity. Reflexivity is a device that is used to vary the distance from a subject, giving the idea that the filmmakers, the product and everything that goes along with it a unity in the production. This style is self-serving in that the filmmakers could be seen prompting the subjects and providing a direct line of questions that they could use to form a solid piece. In the court of law this is called 'leading the witness' in order to get the desired answers that you seek, as opposed to the answers that come naturally from a subject matter that is brought up.

Rouch gives specific questions that lend themselves to specific answers. "I would argue that most anthropologists implicitly believe content should so dominate form in scientific writing that the form and style of an ethnography appears to "naturally" flow out from the content." - (Ruby, Studies in the anthropology of Visual Communication, Pg 106,Vol. 2, No. 2, Fall 1975). In providing specific questions, they do not let the life naturally 'flow' but instead impede it at their own will destroying the illusion that they have created. These filmmakers seem almost like they wish to participate in the very spectacle they wish to show, and cannot distance themselves from the subjects for fear of losing notoriety.

Morin and Rouch are extremely open to their subjects, providing valuable insight into their minds, as well as the minds of the people whom they are interviewing. This certainly provides for honesty in front of the camera creating a cushion of comfort for the subjects so that the camera does not seem to interfere as much a simply record. In certain scenes it seemed as if we were an observer regarding these people with a cold unfeeling eye. The argument in the hallway for example. This does not lend itself to a self-conscious conversation.

There are moments in the film that do seem very contrived however. There is a scene of a woman walking through the streets of Paris along with her walking we hear her telling the story of her father's internment and her own in a Nazi death camp. This is obviously a scripted scene. It lends itself to disbelief when we see that she is walking, lost in thought. The technique of us hearing those thoughts is vital to this disbelief.

The film-making was excellent at times, as I said, giving the sensation of an omniscient- floating eyeball, observing the people at their daily lives. This feeling is ruined however when we are privy to the Rouch's and Morin's conversation on what they feel the outcome of the film represents. It creates a feeling of false voyeurism then, incompatible with the sensitive proximity that we have just watched. The scene in the theater when he shows the characters dissecting each other is especially grating as it lends it self even more to a Dali-esquire surrealism where the characters are watching themselves as we watch them.

Meilleurs choix

Connectez-vous pour évaluer et suivre la liste de favoris afin de recevoir des recommandations personnalisées

- How long is Chronicle of a Summer?Alimenté par Alexa

Détails

- Durée1 heure 25 minutes

- Couleur

- Mixage

- Rapport de forme

- 1.37 : 1

Contribuer à cette page

Suggérer une modification ou ajouter du contenu manquant

Lacune principale

By what name was Chronique d'un été (Paris 1960) (1961) officially released in India in English?

Répondre