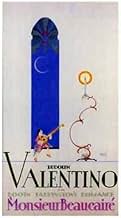

This survives in a crisp, sharp, a very beautiful print in the Library of Congress. The overriding problem with this film is it's director: SIDNEY OLCOTT. Olcott's direction is of the old DW Griffith school of film making. A method of directing by Olcott as can be evidenced in his Marion Davies picture of the previous year, LITTLE OLD NEW YORK. In both 'Beaucaire & 'New York Olcott frustratingly plants his camera for the habitual mid-shots & long-shots and occasional closeup as Griffith had done since before WW1 and was currently still doing. This is fine when doing historical or costume pictures like these to showcase the sets, costumes, hairstyles etc where big money had been spent. But to get us through the story the camera should be a little more fluid, move with the actors through the scenes, involve the audience in the subjective instead of constantly relying on a plethora of title cards. Moving camera literally had been around since motion pictures were invented. And comedies, many by ie Buster Keaton, made ample use of the moving camera. But dramas & specifically those by directors like Griffith & Olcott continued to be filmed with a static stationary camera. Both men had started their film careers about the same time c.1907 and were used to filming one way. That is to frame in complete scenes(long,mid,short)then join all the footage into a story linked by an over abundance of long running title cards. LONY & MB could've both been better if directed by younger up-n-coming more visionary directors like King Vidor or Alan Crosland. The adaptation of the moving roving camera would gain popularity beginning in 1925, after being influenced by European & specifically German films, but came a year too late to help Monsieur Beacaire.

On the brighter side, cinematographer Harry Fischbeck does a nice job of imbuing the sets with the right amount of light & shadow. Not knowing if the scenes were originally tinted & toned, the b/w LOC print was superb with constant projection speed indicating the film was probably photographed at 24 fps. It's fortunate that a marvelous print survives to showcase Fischbeck's efforts. Valentino, powder puff or not, is amusing & subdued in a costume picture that really isn't way over his head. He displays a nice bit of tongue & cheek wonderfully pantomimed by the actor. A really good scene, and one repeated on television, has Valentino leaping over a balcony with sword at his side into the darkness. One can see why documentists would use that scene because it is well done. Other scenes are photographed so crisp and in closeup that lip readers can have a field day 'hearing' what the actors are saying. Indeed Olcott improved in close-ups more here than he had in LONY but Beaucaire is still pedestrian and wont come alive. Legend has it that Natacha Rambova, Valentino's wife, interferred with direction on this film and caused trouble all during the shooting but Olcott's vane directing style is in evidence throughout. Booth Tarkington's novel is a historical-costume-comedy-drama that delves away from the usual slice of Americana he usually put out such as THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS. Valentino fans will have no problem seeing their hero in royal powdered attire. His pleasant appeal still comes through despite Olcott. Valentino will give a similar devil may care performance a year later in THE EAGLE directed by Clarence Brown. Brown, like Vidor & Crosland, was one of a new crop of directors who were soon to adapt the moving camera and almost make it an unassuming character within the story it was filming. Lastly Monsieur Beaucaire has all the right productions(A-List), excellent photography, and probably a decent musical score when it debuted but Sidney Olcott's static is ingrained in the picture. With another newer younger director this picture could've moved and consequently could've ended up being better remembered if not a late silent classic.