Carl Theodor Dreyer is one of those directors, similar to Jean Vigo or Stanley Kubrick, who have achieved legendary status through a handful of films. In Dreyer's case, these are above all his last silent film 'La passion de Jeanne d'Arc' (F 1928) and his first sound film 'Vampyr' (D 1932). In the 32 years that followed, Dreyer only made four more feature films, all of which are as individual as they are impressive. Although Dreyer's early silent films are much more conventional, they already show great care and mastery of the medium.

'Die Gezeichneten' was made in Germany with an international ensemble of actors, based on a Danish novel. Dreyer had previously travelled to Lublin in Poland with his film architects to find inspiration for the film's sets. And so the small Galician town appears authentic, as do its inhabitants. Dreyer, normally a director of quiet tones, had to choreograph and film mass scenes for 'Die Gezeichneten', which he did amazingly well.

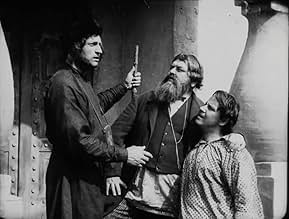

The film tells the story of Russia in 1905, when unrest is spreading among the population and a revolution is imminent. The secret police try to divert the hatred of the population away from the Tsar's family to the Jewish minority in the country. We follow the fates of people who are caught up in this, especially when a pogrom against the Jewish inhabitants of a small town takes place.

The film treats its characters with great empathy and differentiation. We experience the narrowness of the Jewish community from which the siblings Hanne-Liebe (Polina Piekovskaya) and Yakov (Vladimir Gajdarov) try to escape, but at the same time the warmth and security that this community offers its members. There is idealism and heroism among the Russian revolutionaries, but also opportunism and betrayal. The simplicity of the Russian townsfolk and peasants has a naive, homely feel to it, but only until they allow themselves to be incited to carry out a murderous attack on their Jewish neighbours.

If the film succeeds in showing all this without painting it in black and white, it is also because Dreyer is a master of camerawork and editing. As in all his films, he skilfully uses the alternation of close-ups and long shots and, above all, gives us enough time to study faces. Of course, it helps that many of the roles are played by established stage actors, not least from Stanislavsky's Moscow Art Theatre. The parallel montages during the raid on the Jewish neighbourhood show how much Dreyer learned from D. W. Griffith. As in almost all of his films, Dreyer's focus in 'Die Gezeichneten' is on a precise study of the human soul, especially of characters who are under great emotional strain or experiencing spiritual crises. Dreyer is an extremely sensitive observer and a master at translating the results of his psychological analyses into film images in a way that is at times downright devastating.

![Guarda Trailer [OV]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/M/MV5BYWI0YWI1NWUtYmE3NC00NDM0LTg3OTUtM2U4ZDMwNzQ1YmQxXkEyXkFqcGdeQXRyYW5zY29kZS13b3JrZmxvdw@@._V1_QL75_UX500_CR0)