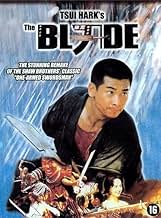

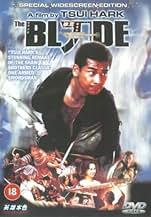

The Blade is a whirlwind of blood, dust, and psychedelic colour. Beneath its rough, brutal appearance lies an uncompromising and technically evolved offering from Hong Kong's prolific director/producer giant Tsui Hark. Based on the old-school kung-fu classic The One-Armed Swordsman, The Blade tells the story of a young man adopted by a renowned blacksmith, who discovers that his true father was killed by superstitiously powerful bandit named Lung, "who it is said can fly!".

When he impulsively goes out seeking revenge, he runs afoul of a gang of desert scum and loses his right arm in the encounter. Ashamed, he goes into hiding but after finding an broken weapon and the tatters of an old swordfighting manual, he begins to come to terms with his self-loathing, and eventually learns to compensate for his loss. With half a sword, half a technique, and still one arm short of a pair, he returns to his old home to confront both his past and the man who murdered his father.

A simple tale of vengeful perseverance here gets a nihilistic gritty art-house treatment. The action takes place in an amoral, almost post-apocalyptic desert landscape. Hark's camera speeds around with abandon, capturing both the bleak setting and the lush expressive palette of the characters' internal emotional landscape. In terms of camera style and visual dynamism, this is Hark's most adventurous film. Although seemingly frantic, it is never random. The cinematography bears a meticulous attention to detail, and the editing has a razor-sharp rhythm of its own.

There's a lot going on under the surface here. The simple story is fleshed out with a dark sensuality. Along with themes of surmounting obstacles through hard work, and misplaced honour in a harsh and selfish world (kung fu movie essentials), we find commentary on lust, gender, and simple pragmatism as well. Early on, a Shaolin monk, icon of heroism, meets a grisly, inglorious end, signifying that this is not just another heroic martial-arts fantasy. And yet heroism survives, in the form of a crippled man with a broken, cleaver-like weapon... just one more way The Blade offers new twists on old conventions.

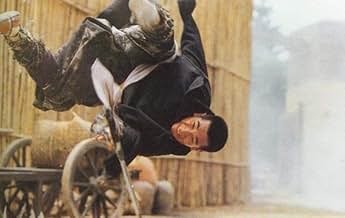

This being a Hong Kong martial-arts movie, the action is to be noted. Where fluid idealized wushu forms might normally prevail, a certain street-level grittiness and desperation takes hold. Even when characters are performing incredible feats, you find yourself thinking "So this is what kung-fu fighting was really like."

Although Chiu Cheuk and villainous Xiong Xin Xin can certainly deliver spectacular physical displays (as seen in Hark's later Once Upon A Time in China films), in The Blade the camera and editing take the lead. While some reviewers tend to forget the "cinema" part of "martial arts cinema", and complain that much of the action is concealed by the breakneck editing and moving camera, there is still an impressive amount of wushu on display in this film, and the frenzied cutting serves to heighten the excitement and the abilities of the performers, even without implied supernatural powers or gratuitous wire stunts. As a result, the final 15 minutes of this movie frame possibly some of the most furious, breathless, vicious fight sequences in cinema history.

Believe it!