An aging doorman is forced to face the scorn of his friends, neighbors and society after being fired from his prestigious job at a luxurious hotel.An aging doorman is forced to face the scorn of his friends, neighbors and society after being fired from his prestigious job at a luxurious hotel.An aging doorman is forced to face the scorn of his friends, neighbors and society after being fired from his prestigious job at a luxurious hotel.

- Awards

- 2 wins

O.E. Hasse

- Small Role

- (uncredited)

Harald Madsen

- Wedding Musician

- (uncredited)

Neumann-Schüler

- Small Role

- (uncredited)

Carl Schenstrøm

- Wedding Musician

- (uncredited)

Erich Schönfelder

- Small role

- (uncredited)

- Director

- Writer

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

Storyline

Did you know

- TriviaThe first "dolly" (a device that allows a camera to move during a shot) was created for this film. According to Edgar G. Ulmer, who worked on the film, the idea to make the first dolly came from the desire to focus on Emil Jannings' face during the first shot of the movie, as he moved through the hotel. They obviously didn't know how to make a dolly technically, so they created the first one out of a baby's carriage. They then pulled the carriage on a sort of railway that was built in the studio.

- GoofsWhen the porter comes home with the stolen coat, the third button down (which fell off earlier) is still there until a close-up of him at the door.

- Alternate versionsThere is an Italian edition of this film on DVD, re-edited in double version (1.33:1 and 1.78:1) with the contribution of film historian Riccardo Cusin. This version is also available for streaming on some platforms.

- ConnectionsFeatured in Deadly Circuit (1983)

Featured review

F. W Murnau works are rare things - he made very few compared to other directors of his day, and many of those he did make have been lost. The reason he made so few can perhaps be understood by watching The Last Laugh. Like Chaplin, Kubrick and Leone, the effort that went into a single picture was the same effort another director might spread across ten. Nosferatu, his famous Dracula story, is great, and i hear his Faust and Sunrise are also things to behold - but many regard "The Last Laugh" as his masterwork, and also one of the greatest movies of all time. Lillian Gish once said that she never approved of the talkies - she felt that silents were starting to create a whole new art form. She was right, but the proof of this can not be seen in the work of Griffith, who was her frequent collaborator, and who she probably was thinking about when she made this statement - but in the work of German director F. W Murnau.

D. W Griffith is usually shunned for his stance on racial issues and praised for his abilities as an influential film artist. I believe he doesn't deserve this praise - and this movie is why. Not only was Griffith about as subtle as a migraine, but watching a Griffith silent, you get more words than images. There's a title card telling you what is about to happen in every image before it does. The images themselves are almost unnecessary - his style is more literary than cinematic. The difference between watching Griffith's Intolerance and watching F. W Murnau's The Last Laugh is like the difference between watching a silent comedy by Hal Roach and one by Charlie Chaplin. The latter of each pair (Murnau and Chaplin) were visualists and artists, using few words, constructing beauty and high emotion through seemingly simple situations (a tramp who discovers a lost child, or a hotel doorman who loses his job, which is the basis of The Last Laugh).

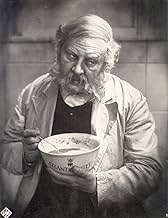

Silent directors strove to and were praised for their ability to tell stories through images alone, as much as possible, and this is one of the reasons silent cinema reached its pinnacle in F. W Murnau's The Last Laugh - which tells the story of a proud hotel doorman (Emil Jennings), who, after many years of service, is demoted from his position to a mens' bathroom attendant. Murnau tells an incredibly sensitive and human tale, showing how much the job meant to him by having him go to work instead of going to his daughter's wedding. He shows how the position made him respected in his neighbourhood, and how he could not face the neighbourhood without his doorman's uniform. And he tells the story almost entirely through images.

There are no title cards telling us what the images are - they are allowed to speak for themselves. The few words used are worked in through letters and signs. Many silent directors cheated and used title cards to explain the images, but only in this movie did the art form of silent movies, which Lillian Gish refers to, take shape.

I was amazed at the level of depth and emotional complexity that Murnau was capable of conveying without resorting to title cards (or their equivalent in talkies, the voice-over). This movie is also notable for its brilliant use of expressionism, and the first brilliant use of a tracking shot. In Murnau's The Last Laugh, silent movies metaphorically were given movement, and learned to run.

D. W Griffith is usually shunned for his stance on racial issues and praised for his abilities as an influential film artist. I believe he doesn't deserve this praise - and this movie is why. Not only was Griffith about as subtle as a migraine, but watching a Griffith silent, you get more words than images. There's a title card telling you what is about to happen in every image before it does. The images themselves are almost unnecessary - his style is more literary than cinematic. The difference between watching Griffith's Intolerance and watching F. W Murnau's The Last Laugh is like the difference between watching a silent comedy by Hal Roach and one by Charlie Chaplin. The latter of each pair (Murnau and Chaplin) were visualists and artists, using few words, constructing beauty and high emotion through seemingly simple situations (a tramp who discovers a lost child, or a hotel doorman who loses his job, which is the basis of The Last Laugh).

Silent directors strove to and were praised for their ability to tell stories through images alone, as much as possible, and this is one of the reasons silent cinema reached its pinnacle in F. W Murnau's The Last Laugh - which tells the story of a proud hotel doorman (Emil Jennings), who, after many years of service, is demoted from his position to a mens' bathroom attendant. Murnau tells an incredibly sensitive and human tale, showing how much the job meant to him by having him go to work instead of going to his daughter's wedding. He shows how the position made him respected in his neighbourhood, and how he could not face the neighbourhood without his doorman's uniform. And he tells the story almost entirely through images.

There are no title cards telling us what the images are - they are allowed to speak for themselves. The few words used are worked in through letters and signs. Many silent directors cheated and used title cards to explain the images, but only in this movie did the art form of silent movies, which Lillian Gish refers to, take shape.

I was amazed at the level of depth and emotional complexity that Murnau was capable of conveying without resorting to title cards (or their equivalent in talkies, the voice-over). This movie is also notable for its brilliant use of expressionism, and the first brilliant use of a tracking shot. In Murnau's The Last Laugh, silent movies metaphorically were given movement, and learned to run.

- Ben_Cheshire

- Dec 22, 2003

- Permalink

- How long is The Last Laugh?Powered by Alexa

Details

- Release date

- Country of origin

- Language

- Also known as

- Poslednji čovek

- Filming locations

- UFA Studios, Berlin, Germany(Studio)

- Production company

- See more company credits at IMDbPro

Box office

- Gross US & Canada

- $94,812

- Runtime1 hour 30 minutes

- Color

- Sound mix

- Aspect ratio

- 1.33 : 1

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content