An aging doorman is forced to face the scorn of his friends, neighbors and society after being fired from his prestigious job at a luxurious hotel.An aging doorman is forced to face the scorn of his friends, neighbors and society after being fired from his prestigious job at a luxurious hotel.An aging doorman is forced to face the scorn of his friends, neighbors and society after being fired from his prestigious job at a luxurious hotel.

- Awards

- 2 wins

O.E. Hasse

- Small Role

- (uncredited)

Harald Madsen

- Wedding Musician

- (uncredited)

Neumann-Schüler

- Small Role

- (uncredited)

Carl Schenstrøm

- Wedding Musician

- (uncredited)

Erich Schönfelder

- Small role

- (uncredited)

- Director

- Writer

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

Storyline

Did you know

- TriviaThe first "dolly" (a device that allows a camera to move during a shot) was created for this film. According to Edgar G. Ulmer, who worked on the film, the idea to make the first dolly came from the desire to focus on Emil Jannings' face during the first shot of the movie, as he moved through the hotel. They obviously didn't know how to make a dolly technically, so they created the first one out of a baby's carriage. They then pulled the carriage on a sort of railway that was built in the studio.

- GoofsWhen the porter comes home with the stolen coat, the third button down (which fell off earlier) is still there until a close-up of him at the door.

- Alternate versionsThere is an Italian edition of this film on DVD, re-edited in double version (1.33:1 and 1.78:1) with the contribution of film historian Riccardo Cusin. This version is also available for streaming on some platforms.

- ConnectionsFeatured in Deadly Circuit (1983)

Featured review

In 1920s Germany, a hotel doorman takes great pride in both his job and the grand uniform that denotes his position. The uniform earns him the unquestioning respect of his neighbours, so when he is demoted through no fault of his own to the lowly position of lavatory attendant, the doorman is devastated. Stealing the uniform that once was his, he makes a sad attempt to fool his neighbours into thinking he still manages the door of the prestigious Atlantic Hotel but, before long, the truth is uncovered, and the respect they once paid him quickly dissolves.

The Last Laugh stands as one of the finest creations of a remarkable director, F.W. Murnau, whose credits include Nosferatu, Faust and Sunrise. Filmed without use of subtitles – and to appreciate what an astounding achievement this is, try imagining a dramatic film made without any form of dialogue today – Murnau crafts a beautiful, compelling and tragic tale that stands as both testimony to his undoubted skills and to the artistic heights to which silent cinema often aspired.

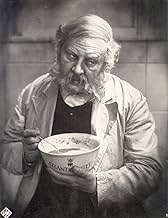

The venerated German actor Emil Jannings was only 40 when he took on the role of the unnamed porter, and yet a combination of Waldemar Jabs painstaking make-up and Jannings' own ability to convey his character's heartache in simple ways, such as the stoop of his shoulders or a bent leg, means he gives a towering performance that never threatens, however, to overshadow the story being told.

The story revolves as much around the grandiose uniform Jannings wears as it does the man. A symbol of the contemporary German importance attached to uniforms and their unavoidably militaristic connotations, the uniform is portrayed as making the man – and it is only the contentious ending that spins the message that it is not uniforms but compassion and kindness that make men great – not only through the respect he receives from all around him, but in the transformation the porter undergoes whenever he is parted from it. From a ramrod-backed creature of magnificence, with elaborately arranged hair and whiskers, he turns into a fumbling old man with bowed back and shaking hands. In the hands of a lesser actor, the demands of this transformation may have descended into cheap caricature, but Jannings never lets us lose sight of the proud man lurking within the bowed and beaten body.

Karl Freund's camera-work is a revelation in this film, right from the opening shot as we descend with the lift into the foyer of the opulent Atlantic hotel. Numerous tricks are used without drawing attention to their use and thus distracting the viewer from the tragedy that is taking place: the drunken POV shot (achieved by strapping the camera to Freund's chest) in Jannings' flat after his niece's wedding reception; the blurred fantasy sequences (themselves a breakthrough in film narrative) achieved by smearing Vaseline onto the camera lens, and the use of dialectic montage and dolly shots, were all groundbreaking techniques never before used, but copied forevermore.

Murnau directs the film with the assurance of a man at the top of his form – where he would arguably remain until his tragically early death – and the care taken with this film is evident throughout every shot. This is why Murnau made relatively few films in an era when many directors churned them out at a rate of a dozen or more per year. The degree of a director's conscientiousness is always evident on the screen, and it is always a pleasure to view a Murnau film, because it is clear that his commitment to his work was always second to none.

The Last Laugh stands as one of the finest creations of a remarkable director, F.W. Murnau, whose credits include Nosferatu, Faust and Sunrise. Filmed without use of subtitles – and to appreciate what an astounding achievement this is, try imagining a dramatic film made without any form of dialogue today – Murnau crafts a beautiful, compelling and tragic tale that stands as both testimony to his undoubted skills and to the artistic heights to which silent cinema often aspired.

The venerated German actor Emil Jannings was only 40 when he took on the role of the unnamed porter, and yet a combination of Waldemar Jabs painstaking make-up and Jannings' own ability to convey his character's heartache in simple ways, such as the stoop of his shoulders or a bent leg, means he gives a towering performance that never threatens, however, to overshadow the story being told.

The story revolves as much around the grandiose uniform Jannings wears as it does the man. A symbol of the contemporary German importance attached to uniforms and their unavoidably militaristic connotations, the uniform is portrayed as making the man – and it is only the contentious ending that spins the message that it is not uniforms but compassion and kindness that make men great – not only through the respect he receives from all around him, but in the transformation the porter undergoes whenever he is parted from it. From a ramrod-backed creature of magnificence, with elaborately arranged hair and whiskers, he turns into a fumbling old man with bowed back and shaking hands. In the hands of a lesser actor, the demands of this transformation may have descended into cheap caricature, but Jannings never lets us lose sight of the proud man lurking within the bowed and beaten body.

Karl Freund's camera-work is a revelation in this film, right from the opening shot as we descend with the lift into the foyer of the opulent Atlantic hotel. Numerous tricks are used without drawing attention to their use and thus distracting the viewer from the tragedy that is taking place: the drunken POV shot (achieved by strapping the camera to Freund's chest) in Jannings' flat after his niece's wedding reception; the blurred fantasy sequences (themselves a breakthrough in film narrative) achieved by smearing Vaseline onto the camera lens, and the use of dialectic montage and dolly shots, were all groundbreaking techniques never before used, but copied forevermore.

Murnau directs the film with the assurance of a man at the top of his form – where he would arguably remain until his tragically early death – and the care taken with this film is evident throughout every shot. This is why Murnau made relatively few films in an era when many directors churned them out at a rate of a dozen or more per year. The degree of a director's conscientiousness is always evident on the screen, and it is always a pleasure to view a Murnau film, because it is clear that his commitment to his work was always second to none.

- JoeytheBrit

- Apr 11, 2010

- Permalink

- How long is The Last Laugh?Powered by Alexa

Details

- Release date

- Country of origin

- Language

- Also known as

- Poslednji čovek

- Filming locations

- UFA Studios, Berlin, Germany(Studio)

- Production company

- See more company credits at IMDbPro

Box office

- Gross US & Canada

- $94,812

- Runtime1 hour 30 minutes

- Color

- Sound mix

- Aspect ratio

- 1.33 : 1

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content