IMDb RATING

7.4/10

1.6K

YOUR RATING

Vienna in the beginning of the twentieth century. Cavalry Lieutenant Fritz Lobheimer is about to end his affair with Baroness Eggerdorff when he meets the young Christine, the daughter of an... Read allVienna in the beginning of the twentieth century. Cavalry Lieutenant Fritz Lobheimer is about to end his affair with Baroness Eggerdorff when he meets the young Christine, the daughter of an opera violinist. Baron Eggerdorff however soon hears of his past misfortune...Vienna in the beginning of the twentieth century. Cavalry Lieutenant Fritz Lobheimer is about to end his affair with Baroness Eggerdorff when he meets the young Christine, the daughter of an opera violinist. Baron Eggerdorff however soon hears of his past misfortune...

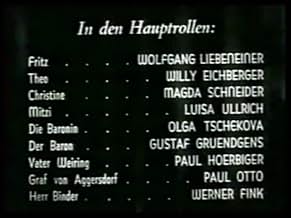

Carl Esmond

- Oberleutnant Theo Kaiser

- (as Willi Eichberger)

Luise Ullrich

- Mitzi Schlager

- (as Luisa Ullrich)

Olga Tschechowa

- Baronin von Aggersdorf

- (as Olga Tschekova)

Gustaf Gründgens

- Baron von Aggersdorf

- (as Gustaf Gruendgens)

Paul Hörbiger

- Vater Weiring

- (as Paul Hoerbiger)

Ekkehard Arendt

- Leutnant von Lensky

- (uncredited)

Werner Finck

- Binder, Cellist

- (uncredited)

Ossy Kratz-Corell

- Der Zugführer

- (uncredited)

Werner Pledath

- Oberst Placzek

- (uncredited)

Featured reviews

The camera of Franz Planer follows the protagonists in long tracking shots, observes precisely the development of an affection and later deep love between Fritz (Wolfgang Liebeneiner) and Christine (Magda Schneider) during the nightly walk through the sleeping city and their endless swings of waltzing through the empty coffee bar. It is also great how Ophüls exemplarily trusts in the viewer's imagination to make things visible. The couple has forgotten the world around them, being only close together, overwhelmed by the feelings, which suddenly arise in them. The slow waltz resembles a soft hug, but the melancholy in this dance is perceptible and especially Fritz, who has a secret tête-à-tête with a bored baroness, seems to fear, that the love for Christine might not have a happy ending.

And last but not least some words about Gustaf Gründgens who plays the cheated baron: In the scenes, he is acting mainly only with looks, with stringent, frigid looks, that whoosh across the room like bullets. The precision of his performance is masterful and probably the best in this film.

And last but not least some words about Gustaf Gründgens who plays the cheated baron: In the scenes, he is acting mainly only with looks, with stringent, frigid looks, that whoosh across the room like bullets. The precision of his performance is masterful and probably the best in this film.

A wonderful picture that shows how early in his career Ophuls mastered melodrama. As melodrama indicates, it's drama with music, and from the start Ophuls sets in motion an operistic, artificial mood. Every performance is self-conscious, aware of being representing; all sets are shown thoroughly, characters leave the scene and the camera remains a few seconds in the empty decor; even the way the snows falls from the sky appears to be fake. Still the film has an admirable freshness and engages the audience in an almost hypnotic trip, to which Ophuls' floating camera and his modern, dramatic use of the score contribute big time. Max Ophuls can be paralleled with Douglas Sirk as a director that purposely breaks up with any trace of reality in order to convey a truth that is purely cinematic.

In the beginning of the Twentieth Century, in Vienna, Dragoon Lieutenant Fritz Lobheimer (Wolfgang Liebeneiner) and Second Lieutenant Theo Kaiser (Carl Esmond) are at the opera when a girl accidentally drops her opera glass. Fritz has a love affair with Baroness von Aggersdorf (Olga Tschechowa) and leaves the opera house to encounter her. Her suspicious husband, Baron von Aggersdorf (Gustaf Gründgens), leaves the opera earlier expecting to catch his wife with her lover but is unsuccessful. Lt. Kaise meets the two girls, Mitzi Schlager (Luisa Ullrich) and Christine Weiring (Magda Schneider), looking for the glass and invites them to go to a cafeteria. Meanwhile, Fritz gives his key to the Baroness and flees from her house. He meets the trio at the cafeteria and while Theo and Mitzi go to his apartment, Fritz walks Christine home. Theo schedules a double date and soon Fritz and Christine fall in love with each other, and Fritz looks for Baroness von Aggersdorf to end their affair. However, the military Graf von Aggersdorf (Paul Otto) tells his brother, Baron von Aggersdorf, the rumors about the relationship of Fritz and his wife. He finds her key and challenges Fritz to a duel, with tragic consequences.

"Liebelei", a.k.a. "Playing at Love" (1933) is a very sad romance by Max Ophüls. The plot is heartbreaking, kind of Romeu & Juliet, about the love of Christine Weiring and Lt. Fritz Lobheimer in the beginning of the last century. In 1958, this romance was remade with the title of "Christine" and Alain Delon in his first lead role and the sweet and lovely Romy Schneider as his romantic pair. Both classy movies are highly recommended. My vote is seven.

Title (Brazil): "Redenção" ("Redemption")

"Liebelei", a.k.a. "Playing at Love" (1933) is a very sad romance by Max Ophüls. The plot is heartbreaking, kind of Romeu & Juliet, about the love of Christine Weiring and Lt. Fritz Lobheimer in the beginning of the last century. In 1958, this romance was remade with the title of "Christine" and Alain Delon in his first lead role and the sweet and lovely Romy Schneider as his romantic pair. Both classy movies are highly recommended. My vote is seven.

Title (Brazil): "Redenção" ("Redemption")

This is Max Ophul's fifth film, his first major success and the first to characterise his inimitable style. The use of Mozart and Beethoven is appropriate here as this film is more classical than his later baroque masterpieces whilst the theme of love as a vicious circle is one that he was to develop to such masterly effect.

Less ironic and more romantic than Schnitzler's original, it also casts a critical eye on the military mentality and Theo's impassioned 'Any shot that is not fired in self defense is murder' would have been sure to rattle a few cages in the Germany of 1933. The director, his art designer and cinematographer have skilfully recreated Imperial Vienna and Ophuls had to wait fifteen years before revisiting the city built on the backlot of Universal for 'Letter from an unknown Woman' which holds the unique distinction of being the only film made in Hollywoodland that is completely European!

A fascinating cast includes some whose careers were to thrive under the Third Reich but whether the adherence of Wolfgang Liebeneiner and Gustaf Gruendgens in particular was genuine or based on sheer opportunism is debatable. Leibeneiner directed the notorious 'Ich Klage an', which promoted the T4 Euthanasia Programme but redeemed himself by later making 'Liebe '47' which showed how 'good people' had been conned by Nazi ideology. The life and career of the classy and mysterious Olga Tschechowa would make a film in itself!

The role of Christine had been played on stage by the superlative Paula Wessely but she was not considered photogenic enough. Ophuls has elicited a magnificent performance from the enchanting Magda Schneider whose utter desolation in her final two minute close-up is one of the most moving on film and years ahead of its time. The remake from 1960 reminds us that Romy Schneider inherited her mother's capacity to tug at the heartstrings.

Ophuls and his family had already fled Germany before the premiere in Berlin with both his name and that of Schnitzler's missing from the titles and the film was subsequently banned by the Allied Commission. Despite these setbacks its brilliance still shone through and in the director's words, " The film was born under a lucky star."

Less ironic and more romantic than Schnitzler's original, it also casts a critical eye on the military mentality and Theo's impassioned 'Any shot that is not fired in self defense is murder' would have been sure to rattle a few cages in the Germany of 1933. The director, his art designer and cinematographer have skilfully recreated Imperial Vienna and Ophuls had to wait fifteen years before revisiting the city built on the backlot of Universal for 'Letter from an unknown Woman' which holds the unique distinction of being the only film made in Hollywoodland that is completely European!

A fascinating cast includes some whose careers were to thrive under the Third Reich but whether the adherence of Wolfgang Liebeneiner and Gustaf Gruendgens in particular was genuine or based on sheer opportunism is debatable. Leibeneiner directed the notorious 'Ich Klage an', which promoted the T4 Euthanasia Programme but redeemed himself by later making 'Liebe '47' which showed how 'good people' had been conned by Nazi ideology. The life and career of the classy and mysterious Olga Tschechowa would make a film in itself!

The role of Christine had been played on stage by the superlative Paula Wessely but she was not considered photogenic enough. Ophuls has elicited a magnificent performance from the enchanting Magda Schneider whose utter desolation in her final two minute close-up is one of the most moving on film and years ahead of its time. The remake from 1960 reminds us that Romy Schneider inherited her mother's capacity to tug at the heartstrings.

Ophuls and his family had already fled Germany before the premiere in Berlin with both his name and that of Schnitzler's missing from the titles and the film was subsequently banned by the Allied Commission. Despite these setbacks its brilliance still shone through and in the director's words, " The film was born under a lucky star."

10J. Steed

Some films cannot be sufficiently qualified by superlatives, and this superb, tranquil, poetic masterpiece is one of them. This film is not just to be watched and enjoyed, but to be felt with all the senses.

Without ever becoming sentimental it tells a very moving love story, but there is a deeper meaning in it (of course already conceived by Arthur Schitzler). We see an artificial Vienna and rigid social rules, but what really is shown is a universal and timeless theme: misplaced (male) honour.

This "misplaced honour" is shown through various male characters, but the most devilish of them is Gustaf Gründgens (absolutely brilliant): was there ever a cigarette smoked as by Gründgens, concentrating all his anger and hate in his smoking. And here we have only one example of Ophüls' idea of letting the image speak: not by dialogue alone (sometimes unintelligible, but this is on purpose!), but by body and camera movement, lightning, editing, sets, the meaning of a scene is told.

This film is superb on all levels, but this is not the place to analyze further (and there are people who are much more capable to do that than I am). I just want to refer to the final sequence (starting with Beethoven's 5th): see how Ophüls, just by perfectly arranging Ullrich, Eichberger and Hörbiger opposite Schneider, gets an image that shows emotional desolation: the party is over, life is over (one must have seen the film to understand this remark) . This culminates in the long, extreme close up of Magda Schneider realizing and trying to come to terms with what has happened; one must have a heart of stone not to get tears into one's eyes or at least a lump in the throat, when seeing this scene. This scene was her moment of triumph; was she ever again as outstanding as in this scene?

Liebelei premiered after the Nazi take-over; it was banned, then - by popular demand - quickly showing was allowed again but only after the names of the jewish contributors were removed. It amazes to know that in 1945 it was banned by the Allies.

Without ever becoming sentimental it tells a very moving love story, but there is a deeper meaning in it (of course already conceived by Arthur Schitzler). We see an artificial Vienna and rigid social rules, but what really is shown is a universal and timeless theme: misplaced (male) honour.

This "misplaced honour" is shown through various male characters, but the most devilish of them is Gustaf Gründgens (absolutely brilliant): was there ever a cigarette smoked as by Gründgens, concentrating all his anger and hate in his smoking. And here we have only one example of Ophüls' idea of letting the image speak: not by dialogue alone (sometimes unintelligible, but this is on purpose!), but by body and camera movement, lightning, editing, sets, the meaning of a scene is told.

This film is superb on all levels, but this is not the place to analyze further (and there are people who are much more capable to do that than I am). I just want to refer to the final sequence (starting with Beethoven's 5th): see how Ophüls, just by perfectly arranging Ullrich, Eichberger and Hörbiger opposite Schneider, gets an image that shows emotional desolation: the party is over, life is over (one must have seen the film to understand this remark) . This culminates in the long, extreme close up of Magda Schneider realizing and trying to come to terms with what has happened; one must have a heart of stone not to get tears into one's eyes or at least a lump in the throat, when seeing this scene. This scene was her moment of triumph; was she ever again as outstanding as in this scene?

Liebelei premiered after the Nazi take-over; it was banned, then - by popular demand - quickly showing was allowed again but only after the names of the jewish contributors were removed. It amazes to know that in 1945 it was banned by the Allies.

Did you know

- TriviaMagda Schneider as a gay musical comedy star had originally been cast for Mizi but Ophuls was inspired to have her exchange roles with the other lead actress and have Luise Ullrich instead play the more light hearted part.

- GoofsAlthough the action takes place well before World War I, the actresses' costumes and hairdos are in the style of 1933.

- ConnectionsAlternate-language version of A Love Story (1933)

Details

Box office

- Gross worldwide

- $852

- Runtime1 hour 28 minutes

- Color

- Aspect ratio

- 1.19 : 1

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content