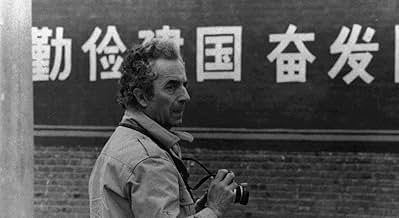

A documentary on China, concentrating mainly on the faces of the people, filmed in the areas they were allowed to visit. The 220-minute version consists of three parts. The first part, taken... Read allA documentary on China, concentrating mainly on the faces of the people, filmed in the areas they were allowed to visit. The 220-minute version consists of three parts. The first part, taken around Beijing, includes a cotton factory, older sections of the city, and a clinic where... Read allA documentary on China, concentrating mainly on the faces of the people, filmed in the areas they were allowed to visit. The 220-minute version consists of three parts. The first part, taken around Beijing, includes a cotton factory, older sections of the city, and a clinic where a Caesarean operation is performed using acupuncture. The middle part visits the Red Flag... Read all