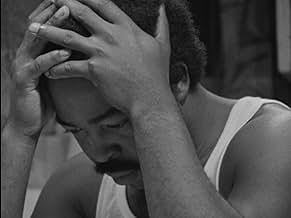

A dramatic look into the life of a family in Watts.A dramatic look into the life of a family in Watts.A dramatic look into the life of a family in Watts.

- Awards

- 4 wins

- Director

- Writer

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

Storyline

Did you know

- TriviaIn 2013, this film was selected by the Library of Congress for preservation in the United States National Film Registry for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

- ConnectionsFeatured in Los Angeles Plays Itself (2003)

Featured review

A landmark film, formally and emotionally pitch-perfect, deceptively modest yet a small-scale domestic study with far wider ramifications, 'Bless their Little Hearts' has deliberately little in the way of plot. We witness Charlie Banks (Nate Hardman) in what appears to be a long-standing routine of unemployment and piece work, the tensions in his marriage to Andais (Kaycee Moore), and the way both parents take out their frustrations on their children. (A particularly painful scene has Charlie castigate his son for not trimming his nails and appearing like a 'girl' or 'sissy'). There's little narrative 'progression' per se: Charlie takes up bits of piece-work (scything grass, painting over Crips graffiti), conducts an extra-marital affair. A lengthy fight with Andais over the affair might, in another film, have been a central or event climactic point. Here, within a matter of scenes, Charlie's back at home, the incident apparently forgotten or at least not talked about, and the routine begins again. Taking up his fishing rod--a memorable scene sees him unpicking the tangled threads when he can't sleep at night--it seems that he's taken up fishing as an attempt to recapture the past, to find some sort of solace. But it turns out that he and his friends are engaging in a money-making scheme, trying to sell fish at roadside to drivers in passing cars. Charlie sits off to the side, smoking and staring off-camera, before walking away from the group towards distance houses: as in the opening scenes, where he wanders home from the welfare office via the railroad tracks, his walk is both purposeful and purposeless, heading somewhere but with no particular place to go. And there the film simply ends.

Woodberry has described the film as "just blues and Brecht". As a write-up for a showing of the film at BAMPFA notes, this is more than just a simple put-down: Woodberry shares with Brecht an emphasis on the gestus, "the seemingly insignificant action that crystallizes for the spectator a whole complex of social relations." If the perpetual condition of unemployment can barely be analysed in the structural terms that produce it, except for the gendered stereotypes of emasculation, of failing to live up to ideals of 'manhood' present in Charlie's quarrels with Andaice and with his mistress, almost every gesture in the film gives testimony to the way these lives are shaped by broader conditions of racialised precarity perhaps the more eloquent for being never directly stated. A scene in which Charlie and his friends go through alternatives to piece-work and unemployment see Charlie reject turning to robbery, not for moral reasons, but because he has a family and a jail term would take him away from them. There's at once a hardened realism, a totally clear-eyed ability to see through the moralistic and hypocritical lies fostered by white supremacist society and a near-fatalistic inability to see an altnerative. When Charlie rides past the ruins of a factory, eloquent testimony to the ravages of deindustrialisation--a scene which memorably plays in the LA Rebellion section of Thom Andersen's 'Los Angeles Plays it Itself'--we're witnessing both broader, contextual illustration and explanation for the entire social situation we've witnessed in claustrophobic miniature throughout, and the near-incidental detail that simply passes the protagonist by on a car-ride home from day labouring, all with no words or externally-imposed explanatory detail. Such a scene is typical of the way the film at once allegorizes and refuses to give up the particularity of the lives we witness on screen. The characters are not heroic exemplars; they are not card-board cut outs; they are not existentialist heroes; they are not objects of pity or scorn one level down from the spectator; they simply are. As in Charles Burnett's 'Killer of Sheep', the film it most closely resembles (Burnett indeed wrote the script and served as cinematographer), music serves the function of the Brechtian chorus, interrupting the action more than illustrating it; it points up the low level misery we see on screen and it provides consolation. The historical nature of the blues and jazz we hear on screen says more than both words and image. It functions as far more than Hollywood soundtracking for the purposes of background, barely-noticeable filler or manipulative emotional guidepost. But it also differs from the hip use of contemporary song in the new Hollywood (exemplified by the Scorsese-Tarantino lineage). We hear both history and the present, how history repeats itself, both how little and how much has changed. Key instances include the opening scenes of Hardman in the welfare office, set to Archie Shepp's achingly fragile soprano saxophone transmutation of Bessie Smith's voice on 'Nobody knows you when you're down out', from the then-recently released 'Trouble in Mind', his second duo record with pianist Horace Parlan; and Esther Philip's voice playing over Kaycee Moore's bus ride, the camera close up on her face as she struggles to awake from sleep, staring off, as so many characters do in this film, into the middle-distance at nothing in particular. Woodberry never shows us what the characters are thinking or feeling at these moments through hackneyed devices like explicatory dialogue or voiceover. Distance is maintained with the refusal to put words in mouths, bridged by the intimate sadness of the music, specific yet archetypal. Woodberry emphasizes that these songs, too, can be cut short, often breaking them off in the middle of a phrase as the screen fades to black and another scene begins. Interrupter, consolation and expression of the inexpressible, music provides the collective eloquence absent from the characters' lives, and attests to the power of survival that subsides even in the bleak normalisation of misery. Nearly forty years after it was made, with socio-political conditions little changed, such compassionate witness resonates as strongly as ever.

Woodberry has described the film as "just blues and Brecht". As a write-up for a showing of the film at BAMPFA notes, this is more than just a simple put-down: Woodberry shares with Brecht an emphasis on the gestus, "the seemingly insignificant action that crystallizes for the spectator a whole complex of social relations." If the perpetual condition of unemployment can barely be analysed in the structural terms that produce it, except for the gendered stereotypes of emasculation, of failing to live up to ideals of 'manhood' present in Charlie's quarrels with Andaice and with his mistress, almost every gesture in the film gives testimony to the way these lives are shaped by broader conditions of racialised precarity perhaps the more eloquent for being never directly stated. A scene in which Charlie and his friends go through alternatives to piece-work and unemployment see Charlie reject turning to robbery, not for moral reasons, but because he has a family and a jail term would take him away from them. There's at once a hardened realism, a totally clear-eyed ability to see through the moralistic and hypocritical lies fostered by white supremacist society and a near-fatalistic inability to see an altnerative. When Charlie rides past the ruins of a factory, eloquent testimony to the ravages of deindustrialisation--a scene which memorably plays in the LA Rebellion section of Thom Andersen's 'Los Angeles Plays it Itself'--we're witnessing both broader, contextual illustration and explanation for the entire social situation we've witnessed in claustrophobic miniature throughout, and the near-incidental detail that simply passes the protagonist by on a car-ride home from day labouring, all with no words or externally-imposed explanatory detail. Such a scene is typical of the way the film at once allegorizes and refuses to give up the particularity of the lives we witness on screen. The characters are not heroic exemplars; they are not card-board cut outs; they are not existentialist heroes; they are not objects of pity or scorn one level down from the spectator; they simply are. As in Charles Burnett's 'Killer of Sheep', the film it most closely resembles (Burnett indeed wrote the script and served as cinematographer), music serves the function of the Brechtian chorus, interrupting the action more than illustrating it; it points up the low level misery we see on screen and it provides consolation. The historical nature of the blues and jazz we hear on screen says more than both words and image. It functions as far more than Hollywood soundtracking for the purposes of background, barely-noticeable filler or manipulative emotional guidepost. But it also differs from the hip use of contemporary song in the new Hollywood (exemplified by the Scorsese-Tarantino lineage). We hear both history and the present, how history repeats itself, both how little and how much has changed. Key instances include the opening scenes of Hardman in the welfare office, set to Archie Shepp's achingly fragile soprano saxophone transmutation of Bessie Smith's voice on 'Nobody knows you when you're down out', from the then-recently released 'Trouble in Mind', his second duo record with pianist Horace Parlan; and Esther Philip's voice playing over Kaycee Moore's bus ride, the camera close up on her face as she struggles to awake from sleep, staring off, as so many characters do in this film, into the middle-distance at nothing in particular. Woodberry never shows us what the characters are thinking or feeling at these moments through hackneyed devices like explicatory dialogue or voiceover. Distance is maintained with the refusal to put words in mouths, bridged by the intimate sadness of the music, specific yet archetypal. Woodberry emphasizes that these songs, too, can be cut short, often breaking them off in the middle of a phrase as the screen fades to black and another scene begins. Interrupter, consolation and expression of the inexpressible, music provides the collective eloquence absent from the characters' lives, and attests to the power of survival that subsides even in the bleak normalisation of misery. Nearly forty years after it was made, with socio-political conditions little changed, such compassionate witness resonates as strongly as ever.

Details

- Release date

- Country of origin

- Language

- Also known as

- ευλογημένες καρδιές

- Filming locations

- See more company credits at IMDbPro

- Runtime1 hour 20 minutes

- Color

- Sound mix

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content

Top Gap

By what name was Bless Their Little Hearts (1983) officially released in Canada in English?

Answer