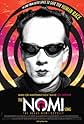

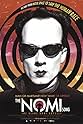

Andrew Horn's The Nomi Song makes no bones about it - performance artist Klaus Nomi was a man of genius. The film is an unapologetic celebration of the mystique of Nomi, the weird brilliance of this late '70s/early '80s New York club phenomenon, who had a minor breakthrough after appearing with David Bowie on Saturday Night Live (he sold well in Europe anyway). If you have no idea who Nomi was then you're not alone; his appeal was purely a cultish one. Those who sing his praises in The Nomi Song - people who were doing lots of drugs in the days they're recounting, it must be pointed out - would have us believe that this was a man of such soaring talent, it would only have been a matter of time before he became famous world-wide. The evidence put forth by Horn - old home videos, some snippets from professionally made programs - would seem to suggest something else, however: a man who, in spite of his obvious talent (he was a trained opera singer, a tenor capable of achieving a haunting falsetto), was always too wrapped up in his own strange, stylized persona to ever really connect with the masses.

The Nomi Song is the portrait of a man who reinvented himself, an exhibitionist who discovered an audience by nullifying every hint of his own personality, and presenting himself as a kind of performing robot. The real Klaus Nomi, we're told, was a sweet, gentle soul, a kid from Berlin who came to New York with dreams of being a star and wound up mopping floors; and the few glimpses we get of Nomi off-stage would seem to uphold this. The real Nomi, it appears, was nothing special, outside of the fact that he could sing (it was his misfortune that there wasn't much market for German tenors who could stretch to a falsetto soprano); the fake Klaus, invented by Klaus as a replacement for the one the world didn't much care for, was a man with a painted face who dressed like a gay Ming the Merciless and sang opera-tinged pop songs in New Wave clubs. People who witnessed Nomi's bizarre, Kabuki-like stage-act gush on and on about what an overwhelming experience it was, but what we see of Nomi, though certainly odd and interesting, fails to convey this feeling. Nothing, we're led to believe, could ever capture the true power of Nomi on-stage. What the film offers us is a tantalizing taste of something eyewitnesses swear was practically transcendent; it's like trying to appreciate the greatness of Robert Johnson by listening to some scratchy old records.

Maybe Nomi was what the film insists he was - a great talent who, by the sad fact of his untimely demise not to mention some egregious mis-management, failed to achieve the stature he seemed destined for. I would tend to doubt it, but the movie makes its argument compellingly, and by placing Nomi in the context of his times, the fag-end of the Andy Warhol days and the beginning of the AIDS horror (Nomi died of the disease), conveys a poignant sense of a lost era, a fondly-remembered scene (the eyewitnesses are all middle-aged, conservative-seeming people; it's hard to imagine them decked out in pink hair and Star Trek get-ups). It finally doesn't matter if Nomi really was what The Nomi Song wants us to think he was (his music was simple-minded and mannered); it matters more that he existed, and embodies in people's minds a certain time and place (those who die young always come to represent the age they lived in; James Dean IS the '50s). The Nomi Song is as much a portrait of the world around Nomi as it is of Nomi, and that world, its strangeness, its lingering energy, is the thing worth remembering.