This is the final post in my series about winning in Wildlife Photographer of the Year 2021. If you read my previous posts, and especially if you watched my award acceptance speech, you might have noticed a message hidden between the lines: I had no intention to enter my photos to the competition. Even though I occasionally enjoy looking through the winning photos in competitions, the truth is it was never my goal to have my photos showcased in one. I just don’t need that external validation. Please don’t confuse this with my reaction to having my photos selected as winners; it is a great honor and it is a humbling experience to see your photos displayed together with some of the world’s best wildlife photographers’ work. What I mean is that photo competitions are not very important to me and I do not photograph with the competitions in mind.

That being said, my experience as someone who won in one of the most prestigious nature photography competitions in the world can be helpful for other people who are considering submitting their work but don’t know what to expect. This post is based on my experience winning in WPY57 in 2021. If you are looking for advice which nature photography competition to choose based on your goals and budget, I highly recommend checking out Jen Guyton’s excellent blog post about the topic. It was written a while ago but she still goes back and updates it occasionally. This post is more about the personal experience that you may have while entering your work to a competition. Before I begin, let me give you the best piece of advice on the matter, which pretty much summarizes everything I am about to write:

Manage your expectations.

Me with two of my Wildlife Photographer of the Year winning images at Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, Canada

Before submitting your work to the competition:

Know why you are submitting. What is your goal? Do you want recognition? Or maybe just exposure? Are you doing this for the award’s monetary prize? Are you hoping this will lead into paid work? This is a personal question and there is no single right answer. Whatever the reason, make sure it is clear to you before you enter.

Curate you collection before submission opens. This is more of a tip, but it will save you so much time later when you select your entries.

Decide which categories in the competition will suit best for your work, and please PLEASE read the category descriptions. They are there for a reason, and they are supposed to help you focus your efforts. Remember you are trying to impress a jury of people with your work in the context of that category.

What is a good photo?

The answer depends on the competition you are entering and the jury. Your photos will be judged by people who do not know you, and most likely also not the subject in your photo. They will judge it by their own criteria, as well as the category’s. This means you have very little control over what is considered by others a good photo. You can just hope to get something that is sufficiently eye catching, novel, and technically solid to draw enough attention.

My winning images in Wildlife Photographer of the Year’s Invertebrate Behavior category, displayed alongside Caitlin Henderson’s katydid photo at Natural History Museum, London, United Kingdom (screenshot taken from New Scientist’s coverage of the exhibition). Notice the order of images is different from one museum to another, and largely depends on the exhibition curators.

During submission period:

Create a collection of all the photos you think are your best work. This collection can contain more images than you will submit eventually, I would say up to twice that amount. Now, carefully select the images that fit best to the category. Ask yourself, is this what the category calls for? Is the photo technically good? (in focus, good lighting, well composed etc’). Does it have an impact? Does it tell a story?

At this stage I encourage you to reach out to fellow photographers for feedback, especially if they already won in competitions, and even to family members and friends to some degree (if they really understand photography). Sometimes we are so biased and emotionally attached to our own work that it is easy to inflate subpar work on one hand, and on the other hand to overlook hidden gems.

Once you narrowed down your selection, comes the part that I personally hate the most – you need to title your images and write captions for them. I would argue that at this stage you should not put much of an effort to write something that would be impressive to read but more of an account of what is shown in the photo. You will get a chance to tweak the text if your photos make it to the second round of judging.

After submitting and paying the fee, you can login again one more time, maybe a few days later, just to make sure that everything is accurate. Then I suggest you leave it and focus your energy on other things.

You see, the wait, and even more so the expectation to know what is going on with your photos, will both haunt you. Many people feel stressed at this stage. They overthink and lose sleep thinking whether they should have submitted or written something else. Do not fall for it. And do not endlessly log into your account to look for updates. That would be a waste of your time.

The wait will probably be agonizing. The anxiety and desire to know whether your photos are doing well will cripple you. But I am here to tell you that the less you think about the competition, the better your response will be to whatever is coming next.

I am actually not going to write much about the second round of judging. I believe the small competitions are missing the stage entirely, and for the bigger ones it is really a means to weed out most of the entries and focus on a small selection. If your photos are selected to move forward you might have more work to do, like writing additional text and providing further information as well as the original files, but otherwise it just means more waiting. If you get rejected at this stage, read on.

After a decision is made:

This is the day, you’re supposed to hear back!

My first tip here is to make sure you check your email spam folder. You never know, the decision email might land there (that actually happened to me! And for a couple of days I had no idea that I had four winning images in WPY). Do not log into your account and refresh the page. This will not help and will only cause you despair. When the competition organizers finally send out the email, trust me it will get to you. Be patient.

From here there are two options, of course:

1. OK, your entries got rejected. Now what? Well, this is the thing. Nothing. Try not to take it personally. If you feel sad, you obviously had some expectations, and maybe some of them are shattered. Try to keep your composure about the rejection and view it from a slightly different perspective. It does not mean that your work is not good, or that someone is trying to hurt you. It only means that in the context of the specific category, your work made a smaller impression on the jury compared to another person’s work. That’s it. And that’s ok. I know it sucks. But you can try again next time, and who knows, the results can be different then. In the meantime, get some ice cream. It helps.

2. Holy crap, you actually won! Scoop yourself a bowl of your favorite ice cream and brace yourself for what’s about to come. Oh boy.

This is where you have to manage your expectations H-a-r-d.

First of all we have to divide the timeline here to pre- and post-announcement.

Pre-announcement of the results to the public:

After receiving the email with the results, you might want to run and tell everyone about your achievement. You’re ecstatic, it’s understandable. However, I would strongly advise against it, and also many of the major competitions have a strict press embargo period until the actual public announcement, during which you are supposed to keep the results secret. Sure, you can tell your partner and some of your family, but I would stop there. There is a very good reason why the results are kept quiet – to maximize the impact during the announcement (more on this later).

During the embargo period you will most likely be asked to provide additional information about the winning photos, including renaming and sometimes even rewriting the caption. If there is an awards ceremony you will be given the details and asked to prepare an acceptance speech and handle media interviews at the event. And if you are one of the lucky photographers, your photos might be chosen as a press release teaser a month before the winners are announced. That’s a lot of fun, because at this point everyone is curious to see the winning images, and your photo gets heaps of attention.

“Beautiful Bloodsucker” spotted at a bus stop in London, United Kingdom (photo by Charlie Heckworth)

Post-announcement of the competition results:

I mentioned that the purpose of the press embargo on the competition results is to maximize the impact during the announcement. The competition organizers actually do their best to put you and your work in the spotlight, so I would definitely take advantage of this. If you are looking into generating income from your photography, and you are among the lucky ones whose photo ends up going viral after the competition results are announced, take every paid opportunity you can get to license it to publishers. Once a photo goes viral its potential to generate revenue decreases exponentially, so make the most of it while you still can. In fact, let’s just get this out of the way first – once the results are announced, and your photos are out there being reported as a news item, they are essentially gone. And what I mean is, it will be very difficult to gain control and stop the snowball effect. News and media outlets will report the news, and from there it will be picked up by online content creators and social media accounts. Some of these will share your work in line with the competition’s terms and conditions (usually an attribution and a reference to the competition). Others will copy and plagiarize, and encourage further unauthorized use. It’s frustrating. Be prepared. At the end of the day, there are paid opportunities for licensing the photo, selling merchandise, as well as interview or public lecture invitations, and you might even be able to generate some income from cases of copyright infringement now that you are an internationally acclaimed award-winning photographer.

One outcome worth mentioning is that very often photo agencies contact competition winners, hoping to recruit them as contributors to their growing collection of licensable images. This is a positive thing, and I highly recommend considering doing so. A good agent works on your behalf to find new ways to use your work for revenue. However, this does not mean you should accept every offer on the table. You need to do your homework here, research the agency to ensure its collection and regular clients fit well with your work. It is also important to negotiate a fair contract (a 50:50 split is normal). Do spend time reading the fine print and make sure you understand what the agency is offering and what it can do for you. Preparing images for an agency requires a lot of work in bulk that includes editing, captioning, and keywording. It is recommended to contact fellow photographers from your field who are represented by the same agency and ask about their experience and overall impression with it.

“Beautiful Bloodsucker” promotional poster spotted at Germering-Unterpfaffenhofen S-Bahn Station in Munich public transport, Germany (photo by Viktor Baranov)

Now, let’s talk about expectations again. Remember what I said? Manage your expectations? This is where it gets interesting. Because even if you won and you are happy, you might still find yourself comparing your experience to that of the other winners. That is normal, but try to keep it under control and not obsess over it. Depending on the photo’s subject matter and occasionally also the photographer’s location, some competition winners experience a jump-start to their career while others get very lukewarm attention. I remember feeling very bitter when I saw other finalists getting assignments and paid offers, especially after I swept the competition with four images, two of which were category winners. However, after thinking about it I realized that I am in a completely different stage in my professional life, as I have already gotten assignments and had my work published even before I entered the competition. Another example is that some photographers are invited to celebrate the exhibition’s opening event, while others don’t even hear about it. It’s important to remember however, it usually has nothing to do with you. In my case, the local museum that hosted the exhibition never bothered to invite any of the local winning photographers to view their work on display, and invited me only after I insisted.

“Beautiful Bloodsucker” spotted on a flier for Museum Mensch und Natur, Munich, Germany (photo by Viktor Baranov)

It was also interesting to compare the number and quality of interviews I got in Canada to those I got from Israel. Interviews can be an amazing experience but they can also be a disaster. For example, I had a live radio interview for which I had to be awake at 4am, and the interviewer quickly shifted the topic from my spider photo to rats for most of my time on air. I think I handled it quite well considering the conditions I was given, but it registered with me as one of the most disrespectful interviews I have ever experienced and overall just not a good look for that show in general. Did I have high expectations? Not really. Would it be nice to have gotten a bit more positive recognition after representing my country? Yes, it would.

There you go, Port Credit, Mississauga. I fixed it for you. (Please, before you go searching for it – this is NOT a real monument. I’m just poking fun.)

And then, there are the public reactions and comments about the competition results. Let’s start with the bad. It is almost guaranteed that you will experience a lot of jealousy coming from other people. And jealousy makes people do interesting things… For starters, some people might inspect your photo and look for something wrong with it. Let’s be honest, we’ve all been guilty of this to some degree. This can be something technical like a sensor dust spot that you forgot to remove, an element out of focus, or a flaw in the composition. But it can also be something more nitpicky, like trying to make a case that your photo does not follow the category description or competition rules. I experienced this when someone questioned the authenticity of the story behind one of my winning images, and I had to go back and look for photos of the location from the time it was taken to prove my case. Not exactly a pleasant experience.

Another manifestation of jealousy is making a nasty or snarky comment. For example, one of the most common comments you get after the winners are announced is something like:

“For wildlife photographer of the year, I’d expect spectacular wildlife images. The kind I’d like to hang on my living room wall. Almost none of these make the cut.” (this is a real comment, by the way)

People have different tastes and preferences, so I totally get it. And I truly believe those who say they can take great if not better photos themselves. The question is why they aren’t submitting those photos to competitions. If you have something better, show us and go for it, enter and win! I’d be the first person to encourage and support you. Another common criticism relies less on the actual photo and more on the act of capturing it, for example I have been told that the camera I used, an almost decade-old Canon 7D, is now obsolete. Sure, but who cares? The piece of gear I used is not what the competition is about, it’s what I was able to produce with it! I have nothing against modern mirrorless cameras. The reason I do not own one at the moment is far more simple and depressing: I’m poor. Probably thanks to all those people freely using my photos without paying any licensing fees.

What I am trying to say is that you have to be mentally prepared for people being rude, smug, know-it-alls, or entitled in the comments. How you choose to deal with it can be very personal, but you don’t always have to be pleasant in response. People seem to forget there’s a person behind every work, and that creators put in a great deal of effort in their work. Nothing is ever perfect, but when things are constantly being pointed out as insufficient, especially with a superiority attitude, and without any positive reinforcement, you can’t expect the creators to be all nice. We have feelings. To the commenters out there I say: a better approach would be to put yourself in the creator’s shoes before posting a comment and see if you’d like to receive it several times a day, on every thing you make and feel proud of.

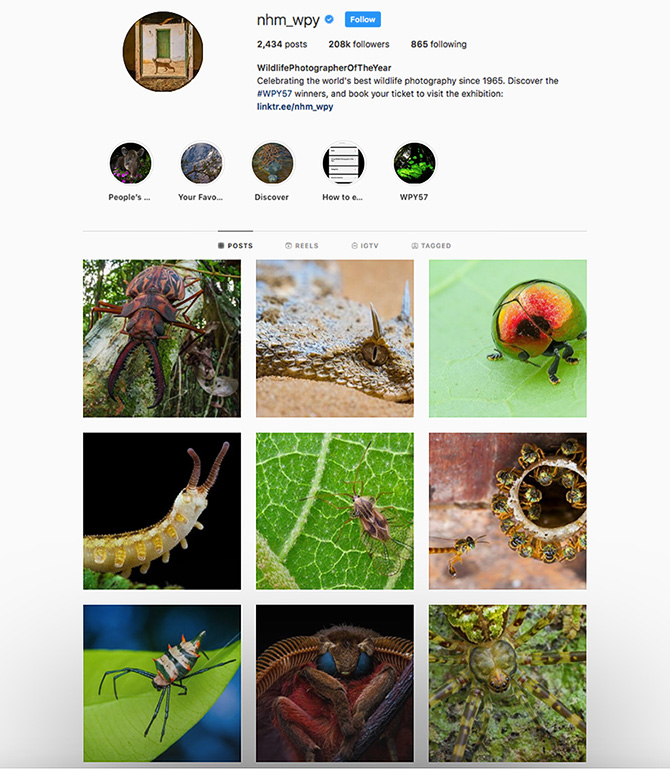

“Gil Week”, social media guest posts on NHM’s Wildlife Photographer of the Year Instagram account

On the positive end, you will most likely gain an immense exposure and following, more people will be familiar with and support your work, and you will inspire others. To me that last bit is really important. You might even get to know some cool new people. I have had amazing conversations with other nature photographers and people who now view insects and spiders differently thanks to my work. I mentioned this in my post about “The Spider Room”, the photo went viral fast and the response was a mix of negatives and positives. The number of people who reached out to me regarding this photo was jaw-dropping, and I had a great time answering questions about it. I’m very happy that it was a conversation starter that made people pause for a moment and think.

Visitors to the Australian National Maritime Museum expressing love for my photo “The Spider Room” (photo by Cassandra Hannagan)

Ok, so after writing this long post about photo competitions, and considering that they are not too important to me, the real question is –

am I going to enter my work to competitions in the future?

Well, the answer is yes, because the positive outcomes far outshine the negative ones, but… I’d pick only one competition that resonates best with me, and enter only ONLY if I have something unique to contribute, like a species or a behavior that has never been captured before, or an unusual composition. There are a couple of reasons for this. Remember that I do not produce my work with a photo competition in mind, but many photographers do spend a great deal of time and planning on it, and this makes winning in the competition very difficult. The other point is that the jury panel evaluates the photos by comparing them to other entries, and there is absolutely no way to know or control how well your photos will perform. In other words, it’s a bit of a gamble. But that’s what makes this game so interesting! As long as you recognize it as such and manage your expectations accordingly, you should be fine.

My winning certificates, book and merchandise from Wildlife Photographer of the Year competition. Not gonna lie, it feels good 🙂

To read part 1 about “The spider room”, click here.

To read part 2 about “Bug filling station”, click here.

To read part 3 about “Beautiful bloodsucker”, click here.

To read part 4 about “Spinning the cradle”, click here.