Unable to find the war he has been asked to cover, a frustrated war correspondent takes the risky path of co-opting the identity of a dead arms-deal acquaintance.Unable to find the war he has been asked to cover, a frustrated war correspondent takes the risky path of co-opting the identity of a dead arms-deal acquaintance.Unable to find the war he has been asked to cover, a frustrated war correspondent takes the risky path of co-opting the identity of a dead arms-deal acquaintance.

- Awards

- 5 wins & 2 nominations total

- Robertson

- (as Chuck Mulvehill)

- Hotel Clerk

- (uncredited)

- Murderer's accomplice

- (uncredited)

- Cameraman

- (uncredited)

Featured reviews

"The Passenger will remain a film of the mid '70s, as one of Antonioni's previous films, Blow-Up, remains a film for and symbolises the '60s. It also contains one of Jack Nicholson's definitive performances (along with Chinatown, The Last Detail and One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest) and has, perhaps, been a trifle overshadowed by these films all emerging within a short period of time of each other and the enormous publicity and word-of-mouth they have generated. But The Passenger has proved itself a strangely durable film and, like Chinatown, one that will remain around for a long time, both in the consciousness of its admirers and, one hopes, constant revivals.

Antonioni's third English-speaking film, The Passenger, like Blow-Up and Zabriskie Point, centres around the oblique, unresolved aspects of life. In Antonioni's films - as in life - there are no easy answers, things are not tidied up, explained, sorted out.

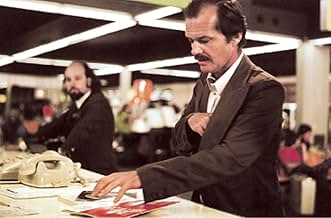

So it is with The Passenger. Jack Nicholson is Locke, an outwardly successful television journalist, but he also is being eaten away by his own disillusionment with the job and the value of his interviews, and that general malaise that affects Antonioni's people. When the film begins, we find him on location in Chad where his jeep breaks down and gets bogged in the sand. Locke breaks down and collapses on the sand as the camera pans away over the strange but beautiful desert panorama.

We next see Locke, in an advanced state of exhaustion, struggling back to his hotel and a cool shower, and discovering that the man in the next room, who looks rather like him, has died. We are very conscious of the stillness in the hotel - the blue walls, a fly buzzing, the noise of the fan, Locke staring intently at the dead man on the bed. We hear their dialogue of the previous evening and the aural flashback changes to a visual one by some very neat editing. Locke changes rooms, passport photos and luggage, and finds it quite easy to take on a new identity. How desperate his need is can be judged by his conversations back in Europe with the free, liberated girl (Maria Schneider) he meets up with. ("I used to be somebody else, but I traded him in"). She, incidentally, is freer than Locke could ever be.

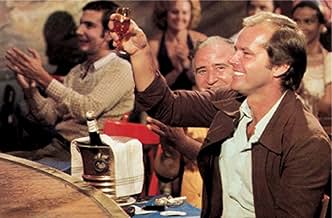

It transpires Locke has taken over the identity of a gun-runner, Robertson. Perhaps it is best not to go into the plot in too much detail. Best all round just to pick out some of the marvellous moments along the way to the final breathtaking conceit. There's Locke, back in London, daringly visiting his old haunts - delighting in being someone else, but of course he isn't. Later on he is suspended in a cable car high about the ocean his arms outstretched like a bird in flight. Later still, the girl asks him what he is running from, and he tells her to turn around and we see what she sees - the road behind them.

By now, we the audience are caught up in this mesmerising film and its deliberations of he mysteries of identity. We are now totally involved in Locke's plight. He has given up one identity for another and becomes more and more helpless as the situation gets out of his control. Finally, in a remote Spanish hotel he can go no further, either as himself or as his new identity, as his wife and the gun-runners close in on him. One shouldn't spoil the last sequence for those still to see it, but it shows the only real freedom from identity and self is in death. The final scene shows us the aftermath: as the sun goes down, the hotel-keeper comes out for a walk, a woman sits in the doorway resting. For some people, who do not question their existence, the continuity of life goes on.

Antonioni, now in his sixties, is one of the great Italian directors who, like Fellini and Visconti, burst upon the international film scene in the late '50s. His trilogy of Italian films, L'Avventura, La Notte and L'Eclisse, and his first colour film The Red Desert (all with Monica Vitti) contributed to the renaissance of the European cinema. Then he switched to his English-speaking films, of which Blow-Up was the first. He is as much a master of landscape as John Ford was in his genre. He thinks nothing of painting whole streets or trees to get the effect he wants. Blow-Up is the only film from the whole, crazy period of Swinging London films that has not dated and which encapsulates what it was really all about. It remains one of the great films. Like Bergman, Bunuel or Fellini you either respond to his vision or reject it totally. His images linger on in the mind, his work never dates."

That is what part of what I wrote in 1976 and The Passenger indeed remains endlessly fascinating and particularly so now that it is available again. Even at the Antonioni retrospective in 2005 it was not available to include in the season, but we did have cast members Jenny Runacre and Steve Berkoff there to speak warmly of it's making and importance.

Let's hope a new generation will discover its timeless appeal, and amazingly Antonioni now in his 90s is still with us, if rather frail. A 2005 short of his was shown last year on the great statue of Moses in Rome and was also in its own way fascinatingly mysterious.

Some may find the opening twenty minutes of the film, where there is virtually no dialogue, hard-going but this perfectly illustrates the sparse and confusing environment of the North African desert where the film begins. We are also treated to a marvellous scene between Locke and the man whose identity he later assumes where a tape recording and flashback are ingeniously merged into one and then separated again. Antonioni creates a mood that is almost indefinable throughout, a kind of hollow detachment which is exactly the perspective that Locke has on the world which has gradually worn him down yet the director still manages to conjure up power and simple romance between Locke and the girl he meets who is played by Maria Schneider. The film was not a hit at the box-office which is not surprising considering it's uncommercial style but artistically and cinematically it is a triumph of innovation.

Thirty years later, Michelangelo Antonioni's re-released "The Passenger" is looking very good, and so are Jack Nicholson and Maria Schneider, as the journalist who takes a dead man's identity in the Sahara and the girl he meets in Barcelona who decides to tag along. David Locke (Nicholson) takes the passport of a man named Robertson who he's had a few drinks with in a hotel. Before that we see Locke experience frustration, giving away cigarettes to men in turbans who say nothing, abandoned by a boy guide, dumping a Land Rover stuck in the sand. Later we see films that show as a journalist he was subservient to bad men. Locke has Robertson's appointment book which leads him to Munich, then various points in Spain. He learns Robertson was a committed man taking risks: he sold arms to revolutionaries whose causes he thought were just. He gets a huge down-payment.

Then Locke's wife gets a tape of him talking to Robertson and his passport with Robertson's photo pasted into it -- and she gets the picture.

Changing your identity and using someone else's isn't just an existential act, it's also a criminal one. Locke's gambit is hopeless: he winds up fleeing from himself. The film skillfully gives its action story an existential underpinning. The chase keeps up a rapid pace, like the Bourne franchise, but it has time to contemplate Locke's old and new lives in a metaphorical story he tells Schneider about a blind man that explains how he ends up.

Antonioni is great at little incidentals -- a girl chewing bubblegum, a man reciting in a Gaudi building. And at the end, people coming and going in a desolate plaza outside a bullfighting amphitheater. The locations provide exotic glamor. The camera-work of course is wonderful. In retrospect now one can see this was definitely a culmination for Antonioni. He thought it technically his best film. This is the director's preferred European version, originally released as "Professione: Reporter."

"I'd like to enquire about flights," Locke asks a hotel clerk. He seeks to escape his past. Later in the film, as he rides a cable cart, Locke spreads his arms and soars like a bird. He's flying, finally enjoying a brief moment of freedom.

The theme of identity, and Locke's name itself, immediately recalls the writings of English philosopher John Locke. Locke believed in the concept of the "tabula rasa" or blank slate. He believed that it was our experiences that defined us as people and that the only way to escape who we are is to effectively erase our history and cut ourselves off from experiences.

Throughout his writings, Locke emphasised the individual's freedom to author his or her own soul. Each individual was free to define his character, but his basic identity as a member of the human species could not be altered. So Locke had two ideas at war. Firstly the belief that the individual was free to author his own life, and secondly the belief that human nature is rigid and unchangeable. It is from this presumption of a free, self authored mind, combined with a sense of rigid human nature, that the Lockean doctrine of "natural" rights is derived.

In Antonioni's film, Nicholson articulates these ideas himself. He is trapped between wanting to be free and having to fulfil duties/roles/tasks embedded in the new persona he has acquired. While responding to a comment that all PLACES are the same, he even argues that it's actually the PEOPLE that are the same. That everyone conforms to specific cultural archetypes. The film's original title, "Profession: Reporter", highlights this point best.

Nicholson's character is desperate to escape this. Like his character in "Five Easy Pieces", he wants some unmappable freedom. He wants to be an individual. Beyond this, though, he wants to stay blank. In what is perhaps the film's most joyous moment, a female character asks Locke what he's running from. He tells her to turn her back to the front of the car. What occurs next is an instant of spontaneous elation and giddy happiness, as she watches the road rush away behind them.

But what people fail to notice during this scene, is that she is in fact watching the past. By facing her previous experiences (which Locke refuses to do) she is happy. Happiness comes from her memories and past encounters, while Locke is miserable simply because he refuses to acknowledge his past experiences.

Throughout the film Locke is asked whether he thinks "the landscape" is beautiful. Once he answers "no", another time he absent mindedly answers "yes", but Antonioni stresses that Locke is really not paying attention. Locke intentionally avoids absorbing beauty or new experiences in an effort to remain in a constant state of rebirth.

These themes are culminated in a brilliant "blind man" story towards the end of the film. Locke, a journalist who specialises in seeing and recording the truth, is painfully attuned to what he calls the "dirt" of the world. As such, he chooses to remain blind. A blank slate.

Antonioni is particularly good at endings and the final shot of "The Passenger" really elevates the whole film. Like the dead man, whose identity he took on, Locke dies alone and face down in a bed. His ex wife pops up and states that she never knew him, but nobody seems to care.

9/10- A great film, worth two viewings. It captures a profound sense of isolation and sadness. Antonioni's camera seems to capture the immense tiredness of the body. Rather than portray experiences, he shows what remains of past experiences. He shows what comes afterwards, when everything has been said. The middle portion of the film is slow and seems to be lacking some sort of superficial drama, but things build nicely and the final payoff well is worth the wait.

Did you know

- TriviaWhen Michelangelo Antonioni received his honorary Oscar in 1995, the Academy asked Jack Nicholson to present it to him.

- GoofsThere are a couple of inaccuracies in the displayed details of Locke's Air Afrique air ticket that was evidently issued in Douala, Cameroon in August 1974. The name of Fort-Lamy (Chad's neighboring capital city) became N'djamena in early 1973, and Paris is written in Italian ("Parigi") which would not have occurred in French-speaking Douala.

- Quotes

The Girl: Isn't it funny how things happen? All the shapes we make. Wouldn't it be terrible to be blind?

David Locke: I know a man who was blind. When he was nearly 40 years old, he had an operation and regained his sight.

The Girl: How was it like?

David Locke: At first he was elated... really high. Faces... colors... landscapes. But then everything began to change. The world was much poorer than he imagined. No one had ever told him how much dirt there was. How much ugliness. He noticed ugliness everywhere. When he was blind... he used to cross the street alone with a stick. After he regained his sight... he became afraid. He began to live in darkness. He never left his room. After three years he killed himself.

- Crazy creditsLeo, the MGM lion, which normally precedes the opening credits of MGM movies, has been supplanted by "BEGINNING OUR NEXT 50 YEARS". Leo then returns in the center with "GOLDEN ANNIVERSARY" on either side of it.

- Alternate versionsSeven minutes were added to the 2005-2006 re-release version, including a brief shot of a nude Maria Schneider in bed with Jack Nicholson in the Spanish hotel.

- ConnectionsFeatured in Z Channel: A Magnificent Obsession (2004)

- How long is The Passenger?Powered by Alexa

Details

- Release date

- Countries of origin

- Official site

- Languages

- Also known as

- Zanimanje: reporter

- Filming locations

- Fort Polignac, Algeria(desert scenes, setting: Chad)

- Production companies

- See more company credits at IMDbPro

Box office

- Gross US & Canada

- $620,155

- Opening weekend US & Canada

- $24,157

- Oct 30, 2005

- Gross worldwide

- $818,936