IMDb RATING

6.9/10

1.6K

YOUR RATING

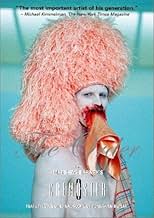

The third film of a five-part art-installation epic -- it's part-zombie movie, part-gangster film.The third film of a five-part art-installation epic -- it's part-zombie movie, part-gangster film.The third film of a five-part art-installation epic -- it's part-zombie movie, part-gangster film.

Peter Donald Badalamenti II

- Fionn MacCumhail

- (as Peter D. Badalamenti)

Todd Christian Hunter

- Mason

- (as Todd Hunter)

- Director

- Writer

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

6.91.5K

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Featured reviews

Monolithic

Glen Helfand of The Guardian was particularly astute in likening Matthew Barney's "Cremaster" films to the 'Star Wars' films. While most 'Star Wars' fanatics would walk out on the "Cremaster" films, these works, like Lucas' series, create a completely new and strange world, with each subsequent film exploring and elaborating that world.

It's easy and lazy to dismiss Barney's work as pretentious. Of course it's pretentious. It's also important. What Barney is doing is taking arcane symbols, myths and images (related to Mormonism, Freemasonry, the reproductive system, historical figures, geographic locations, etc) and making them more arcane by using them as not only the motifs in his films, but the foundations. This is pure cinematic mutation, as Barney assembles these symbols and elements and does with them what David Cronenberg does with flesh and metal. Humans and objects in The Cremaster Cycle do not behave in a recognizable way. They interact with one another in a manner that goes beyond ritualism into the realm of necessity. They're partaking in processes, not performing rituals. As The Loughton Candidate in "Cremaster 4" tap-dances his way into a womb-like tunnel inside the earth under the Isle of Man, or as a character known as 'Goodyear' incubates in a dirigible while eating grapes and excreting them through her shoe in "Cremaster 1," one realizes that these human-like figures are more like insects in their behavior. The Cremaster Cycle establishes a world in which human beings and objects behave without will, like the cells in our body or the neurons in our brain.

"Cremaster 3," three hours long, is the last film in the five-part Cremaster Cycle, and serves as a culmination -- Barney explained that he wished for the Cycle to end in the middle, as though overlooking the other two films in the series as a skyscraper might. Incidentally, one of the two primary locations used in "Cremaster 3" is The Chrysler Building, which is given a sinister, demonic presence here (as in "The Caveman's Valentine" -- what is it about the Chrysler Building?) as it becomes a vessel for all sorts of grisly goings-on. A protracted demolition derby sequence set in the Chrysler building lobby depicts a gang of five late '60s model Chryslers pummeling a vintage Chrysler, intercut by scenes of the renovation of the building's exterior -- drawing a parallel between violence and progress. The curious achievement of this sequence is that it's brutally violent and eventually hard to stomach, yet its violence is amongst vehicles, not living beings.

"Cremaster 3" is beautifully scored by Jonathan Bepler, with some arresting interactions between the music and the images. An intermission occurs at the halfway point, before which the narrative builds to a near-climax of overwhelming power (another such climax closes the film), another surprising accomplishment given Cremaster's completely alien course of events. And Barney's idea of parody is to dehumorize slapstick comedy by making it eerie, in a bar scene (redolent of Kubrick's 'The Shining') featuring the underused and distinctive-looking Terry Gillespie.

It's easy and lazy to dismiss Barney's work as pretentious. Of course it's pretentious. It's also important. What Barney is doing is taking arcane symbols, myths and images (related to Mormonism, Freemasonry, the reproductive system, historical figures, geographic locations, etc) and making them more arcane by using them as not only the motifs in his films, but the foundations. This is pure cinematic mutation, as Barney assembles these symbols and elements and does with them what David Cronenberg does with flesh and metal. Humans and objects in The Cremaster Cycle do not behave in a recognizable way. They interact with one another in a manner that goes beyond ritualism into the realm of necessity. They're partaking in processes, not performing rituals. As The Loughton Candidate in "Cremaster 4" tap-dances his way into a womb-like tunnel inside the earth under the Isle of Man, or as a character known as 'Goodyear' incubates in a dirigible while eating grapes and excreting them through her shoe in "Cremaster 1," one realizes that these human-like figures are more like insects in their behavior. The Cremaster Cycle establishes a world in which human beings and objects behave without will, like the cells in our body or the neurons in our brain.

"Cremaster 3," three hours long, is the last film in the five-part Cremaster Cycle, and serves as a culmination -- Barney explained that he wished for the Cycle to end in the middle, as though overlooking the other two films in the series as a skyscraper might. Incidentally, one of the two primary locations used in "Cremaster 3" is The Chrysler Building, which is given a sinister, demonic presence here (as in "The Caveman's Valentine" -- what is it about the Chrysler Building?) as it becomes a vessel for all sorts of grisly goings-on. A protracted demolition derby sequence set in the Chrysler building lobby depicts a gang of five late '60s model Chryslers pummeling a vintage Chrysler, intercut by scenes of the renovation of the building's exterior -- drawing a parallel between violence and progress. The curious achievement of this sequence is that it's brutally violent and eventually hard to stomach, yet its violence is amongst vehicles, not living beings.

"Cremaster 3" is beautifully scored by Jonathan Bepler, with some arresting interactions between the music and the images. An intermission occurs at the halfway point, before which the narrative builds to a near-climax of overwhelming power (another such climax closes the film), another surprising accomplishment given Cremaster's completely alien course of events. And Barney's idea of parody is to dehumorize slapstick comedy by making it eerie, in a bar scene (redolent of Kubrick's 'The Shining') featuring the underused and distinctive-looking Terry Gillespie.

And don't forget to stop in the museum's gift shop as you leave the theater

Curiosity seekers

seek no more. Pretentious and `arty' could describe it

but I have to say I thought some very good work went into the production design and music. Less such into the "story". It's the top of the Matthew Barney pyramid of art films, culminating in a three hour orgy of celtic mythology, masonic legend, truly retch inducing reverse dental surgery, hardcore punk bands, beautiful models with masonic symbol pasties, double amputee model Aimee Mullins as a catwoman and with clear acrylic prosthetic legs, artist Richard Serra tossing molten vaseline against the walls of the Guggenheim, a sojourn up the elevator shafts of the Chrysler Building, a demolition derby in same's lobby

shall I go on? All the above said, the movie is still truly what it advertised itself to be. The same couldn't be said of many truly awful commercial films, i.e., "Gods and Generals" or "Gigli." You get the broken promises of entertainment and/ or involving historical drama. With C3, you get a chariot race with zombie horses, covered in blankets with the `Cremaster 3' crest emblazoned on them. And don't forget to stop in the museum's gift shop as you leave the theater. Thank you.

Matthew Barney kicks narrative to the curb.

Though Matthew Barney doesn't identify himself as a filmmaker per se -- he's a sculptor by training and practice -- his Cremaster Cycle has me convinced that he has a more expansive vision for the possibility of cinema than any new director since Godard grabbed the audience by the hair and pulled us behind the camera with him.

I think part of Barney's resistance to the filmmaker label is that, like the rest of the world, he's been conditioned to believe that movies are only intended to serve a limited set of purposes, namely to act as filmed imitations of ankle-deep novels or plays; that a literal narrative, propelled throughout by actors talking, is the essential element of any movie. This model has been so deeply embedded in all of our psyches that even when a guy like Barney says "f*&^k all that" and defies every conceivable convention, he still feels as though he's doing something which is only nominally a film, even if it is in fact the opposite: a fully realized motion picture experience.

For those who don't know, The Cremaster Cycle is Barney's dreamlike meditation on ... well, I guess it'd be up to each viewer to decide exactly what the topics are, since the movies deliberately make themselves available for subjective interpretaton. Clearly Barney has creation and death on his mind, as well as ritual, architecture and space, symbolism, gender roles, and a Cronenbergian fascination with anatomy.

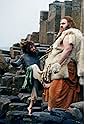

The movies are gorgeously photographed in settings that could only have been designed by someone with the eye of a true visual artist. In the first half of "3," Barney reimagines the polished interiors of the Chrysler Building as a temple in which the building itself is paradoxically conceived. The second half, slightly more personal, has Barney's alter ego in garish Celtic dress scaling the interior of a sparse Guggenheim Museum, intersecting at its various levels what are presumably various stages of his own artistic preoccupations -- encounters with dancing girls, punk rock, and fellow modern artist Richard Serra, among others.

In the end, what kind of movie is it? It certainly isn't the kind of movie that'll have Joel Silver sweating bullets over the box-office competition. Nor is it likely that more than three or four Academy members will see it, though nominations for cinematography and art direction would be well-deserved. It sure isn't warm and fuzzy: for my money, it might be a little too designed, too calculated. I always prefer chaotic naturalism over studious control. Friedkin over Hitchcock for me. It *is* the kind of movie that the most innovative mainstream filmmakers will talk about ten and twenty years from now when asked what inspired them. Barney's willingness to work entirely with associative imagery, to spell out absolutely nothing, and to let meaning take its first shape in the viewer's imagination, is the kind of catalyst that gives impressionable young minds the notion they can do something they didn't before think possible.

I think part of Barney's resistance to the filmmaker label is that, like the rest of the world, he's been conditioned to believe that movies are only intended to serve a limited set of purposes, namely to act as filmed imitations of ankle-deep novels or plays; that a literal narrative, propelled throughout by actors talking, is the essential element of any movie. This model has been so deeply embedded in all of our psyches that even when a guy like Barney says "f*&^k all that" and defies every conceivable convention, he still feels as though he's doing something which is only nominally a film, even if it is in fact the opposite: a fully realized motion picture experience.

For those who don't know, The Cremaster Cycle is Barney's dreamlike meditation on ... well, I guess it'd be up to each viewer to decide exactly what the topics are, since the movies deliberately make themselves available for subjective interpretaton. Clearly Barney has creation and death on his mind, as well as ritual, architecture and space, symbolism, gender roles, and a Cronenbergian fascination with anatomy.

The movies are gorgeously photographed in settings that could only have been designed by someone with the eye of a true visual artist. In the first half of "3," Barney reimagines the polished interiors of the Chrysler Building as a temple in which the building itself is paradoxically conceived. The second half, slightly more personal, has Barney's alter ego in garish Celtic dress scaling the interior of a sparse Guggenheim Museum, intersecting at its various levels what are presumably various stages of his own artistic preoccupations -- encounters with dancing girls, punk rock, and fellow modern artist Richard Serra, among others.

In the end, what kind of movie is it? It certainly isn't the kind of movie that'll have Joel Silver sweating bullets over the box-office competition. Nor is it likely that more than three or four Academy members will see it, though nominations for cinematography and art direction would be well-deserved. It sure isn't warm and fuzzy: for my money, it might be a little too designed, too calculated. I always prefer chaotic naturalism over studious control. Friedkin over Hitchcock for me. It *is* the kind of movie that the most innovative mainstream filmmakers will talk about ten and twenty years from now when asked what inspired them. Barney's willingness to work entirely with associative imagery, to spell out absolutely nothing, and to let meaning take its first shape in the viewer's imagination, is the kind of catalyst that gives impressionable young minds the notion they can do something they didn't before think possible.

An elitist "Art" film

This film is painfully boring! It's also way too long. It was so bad that I started staring at the walls and ceiling of the theater rather than look at the screen. Not one moment of each inexplicable sequence really resonated with me in the slightest. I think at least eight or more people left the theater before it was finished.

There is no plot at all. That in itself doesn't bother me, I don't think that a film necessarily has to have a narrative structure. However, the way in which this was done just didn't work for me. I've seen a lot of comparisons to David Lynch in people's comments. I personally don't see it. I love most of Lynch's films.

It seemed like the sort of film that an autistic person would make, cold and lifeless with no discernible emotion. The film treats inanimate objects and people almost as if they were the same. There is very little humanity or empathy to be found anywhere. Not to mention that there's no dialog.

I just couldn't relate to it at all.

There is no plot at all. That in itself doesn't bother me, I don't think that a film necessarily has to have a narrative structure. However, the way in which this was done just didn't work for me. I've seen a lot of comparisons to David Lynch in people's comments. I personally don't see it. I love most of Lynch's films.

It seemed like the sort of film that an autistic person would make, cold and lifeless with no discernible emotion. The film treats inanimate objects and people almost as if they were the same. There is very little humanity or empathy to be found anywhere. Not to mention that there's no dialog.

I just couldn't relate to it at all.

Can't say I understood, but it's been haunting me

When I got out of the theater after seeing this movie, I was stuck with one major question: how does one get the financing to make such a movie? How do you sell a movie so unusual to investors?

I must admit I desperately wanted this movie to make sense. I wanted the mason to have a legitimate reason to fill an elevator with concrete, and I wanted this reason explained later on in the movie, but I could tell the answer would never come. I know my expectations were conditioned by years of conventional cinema and storytelling. For this reason alone, Cremaster was worth watching. It stirred me up, exposed me to very personal and thorough symbolism, and made no apologies.

This movie is not cinema as you've come to know it, it's performance art caught on film. I've heard that the artist explains a lot of his symbolism on his website but I'm not sure I want to know, at least for now. I'd rather let the images simmer in my mind for a few weeks and let meaning bubble up. For now, three days after seeing it, I'd say the movie is basically about the powerlessness of the individual against the powers that be and the necessity for an artist to pander to those powers to achieve his vision. This necessity is also the struggle that drives the creative process. Lackeys and employees are numbed by their position, and some of them express themselves in a creative way to alleviate the numbness and feel alive. Whether they succeed or not is not the point.

I must admit I desperately wanted this movie to make sense. I wanted the mason to have a legitimate reason to fill an elevator with concrete, and I wanted this reason explained later on in the movie, but I could tell the answer would never come. I know my expectations were conditioned by years of conventional cinema and storytelling. For this reason alone, Cremaster was worth watching. It stirred me up, exposed me to very personal and thorough symbolism, and made no apologies.

This movie is not cinema as you've come to know it, it's performance art caught on film. I've heard that the artist explains a lot of his symbolism on his website but I'm not sure I want to know, at least for now. I'd rather let the images simmer in my mind for a few weeks and let meaning bubble up. For now, three days after seeing it, I'd say the movie is basically about the powerlessness of the individual against the powers that be and the necessity for an artist to pander to those powers to achieve his vision. This necessity is also the struggle that drives the creative process. Lackeys and employees are numbed by their position, and some of them express themselves in a creative way to alleviate the numbness and feel alive. Whether they succeed or not is not the point.

Did you know

- GoofsAfter the teeth have begun to exit the Apprentice's prolapsed intestine, there is an overhead shot of the hitmen standing around the Apprentice on the dentist's chair. The view of the intestine is slightly blocked by the back of one of the hitmen, but as he shifts from side to side, the teeth are nowhere to be seen.

- ConnectionsEdited into The Cremaster Cycle (2003)

- How long is Cremaster 3?Powered by Alexa

Details

Box office

- Gross US & Canada

- $120,308

- Opening weekend US & Canada

- $9,787

- May 21, 2010

- Runtime

- 3h 2m(182 min)

- Color

- Sound mix

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content