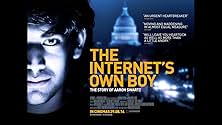

The story of programming prodigy and information activist Aaron Swartz, who took his own life at the age of 26.The story of programming prodigy and information activist Aaron Swartz, who took his own life at the age of 26.The story of programming prodigy and information activist Aaron Swartz, who took his own life at the age of 26.

- Awards

- 4 wins & 4 nominations total

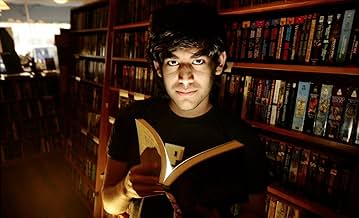

Aaron Swartz

- Self

- (archive footage)

Stephen Heymann

- Self - Asst. U.S. Attorney Massachusetts

- (archive footage)

- Director

- Writer

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

8.018.4K

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Featured reviews

It's a sad story, but one worth hearing

I don't know why the Aaron Swartz story was never on my radar, which is one of the reasons why The Internet's Own Boy was an eye-opener. His is a tragic story, and although the filmmakers secured screen time with (almost) all involved, it's sad that all we have from Swartz is archival webcam interview footage. The movie makes a persuasive case for his being made a high-profile example by the justice system, and there's enough here to leave you either irate or fearful (or both).

Whether or not you agree with the man's politics, he made a difference - hell, he was instrumental in getting SOPA struck down, so he deserves our respect for that - and his story brings to light the need for fine-tuning the ancient copyright laws. Either way, this documentary delivers.

7/10

Whether or not you agree with the man's politics, he made a difference - hell, he was instrumental in getting SOPA struck down, so he deserves our respect for that - and his story brings to light the need for fine-tuning the ancient copyright laws. Either way, this documentary delivers.

7/10

On liberty and naiveté

Aaron Swartz was an internet hacker and activist who committed suicide under pressure from a U.S. government attempt to prosecute him for a crime (stealing data) where he meant no harm and sought to make no money. I certainly agree that the legal case against Swartz was absurdly overcooked; but the film throws up a number of interesting issues about theories of government in general, and the techno-utopian world-view that Schwarz subscribed to. Technological advance can make previous ways of doing things obsolete, and measures of control superfluous and/or unnecessary. They threaten vested interests (or, more probably, they threaten to replace an old elite whose interests are vested in the old technology with a new one unencumbered by attachment to the past). One can believe these changes are good in themselves; one can believe the death of the old control structures is an added bonus; one can believe that the changes are good precisely because they lead to the end of the old control structures. And this way of thinking (in the context of technologies for the storage and dissemination of data) leads to the idea that 'data wants to be free'; and that any attempt to restrict data availability is a form of human rights violation. This leads to some strange positions. For example, academic journals have existed, in some cases for hundreds of years, because publication has been intrinsically difficult. Now, it's easier, the traditional model may be obsolete, and of course, the publishers fight changes that threaten to end their cosy oligopoly. And yet, for an academic journal publisher to seek to defend their copyrighted material is not evil (unless one believes in the complete abolition of intellectual property, which is a different kind of argument). Being on the wrong side of history is ultimately a practical matter, not a moral one. And new models of publishing still come at a cost and still have to be paid for - data is not free (in that other sense of freedom) and in a world with differential ability to pay, that means it cannot be universally free in the other sense either.

And as a scientist, supportive of the principle of open access, I find myself in agreement with most of Swartz's positions; and yet alienated by his friends and collaborators, who insist that the government should not have prosecuted Schwarz at all, basically because he was right and they were wrong. One really doesn't need a very advanced theory of power to see that this is a naive way of looking at the world, or an advanced theory of psychology to consider it an arrogant one. The world needs its Aaron Swartz's, and a wise and humane government would not seek to hand down excessive sentences on such people merely to assert its own right to make the rules. But the world also needs people to (mostly) obey the law, and while there may be many decisions of government that people might justly object to on grounds of conscience, Swartz's objections to copyright law lie mainly in the fact that it prevented him from doing cool and interesting things. I find myself in support of most of Swartz's specific views, yet sometimes I feel as scared of libertarians of left (like Swartz) and right as I am of the big government they oppose, whose optimism is invigorating yet in some senses selfish, with their apparent belief that government's worst crime is acting to prevent brilliant and privileged people from reaching the height of their potential. Whatever, it's a documentary that certainly makes you think, but one should screen the views of Scwartz's acolytes before swallowing them in their entirety.

And as a scientist, supportive of the principle of open access, I find myself in agreement with most of Swartz's positions; and yet alienated by his friends and collaborators, who insist that the government should not have prosecuted Schwarz at all, basically because he was right and they were wrong. One really doesn't need a very advanced theory of power to see that this is a naive way of looking at the world, or an advanced theory of psychology to consider it an arrogant one. The world needs its Aaron Swartz's, and a wise and humane government would not seek to hand down excessive sentences on such people merely to assert its own right to make the rules. But the world also needs people to (mostly) obey the law, and while there may be many decisions of government that people might justly object to on grounds of conscience, Swartz's objections to copyright law lie mainly in the fact that it prevented him from doing cool and interesting things. I find myself in support of most of Swartz's specific views, yet sometimes I feel as scared of libertarians of left (like Swartz) and right as I am of the big government they oppose, whose optimism is invigorating yet in some senses selfish, with their apparent belief that government's worst crime is acting to prevent brilliant and privileged people from reaching the height of their potential. Whatever, it's a documentary that certainly makes you think, but one should screen the views of Scwartz's acolytes before swallowing them in their entirety.

A good documentary of a very important subject.

This is a very good documentary of a subject that EVERYONE should be interested in. If you're interested in the Internet, technology, open publishing (science or law), or freedom, you MUST watch this documentary. It's a moving and disturbing story of a very important young man, and how the government tried to make an example out of him.

Where it fails, is dealing with Aaron's mental health issues. His struggles with depression (which he documented in his blog) were glossed over, and even dismissed (such as when he brother said he didn't remember any mood swings as a child). I think this was purposefully done to fit the thesis of the documentary (that the prosecution backed him into a corner), and ignores a major part of Aaron's life. Just because he was "at-risk" due to mental illness, doesn't mean he wasn't targeted and persecuted. Instead, his depression was swept under the rug by the filmmaker, as it so often is in our society.

Overall, this is a very important film and I would highly recommend it. However, read Aaron's blogs and writings for supplemental info!

Where it fails, is dealing with Aaron's mental health issues. His struggles with depression (which he documented in his blog) were glossed over, and even dismissed (such as when he brother said he didn't remember any mood swings as a child). I think this was purposefully done to fit the thesis of the documentary (that the prosecution backed him into a corner), and ignores a major part of Aaron's life. Just because he was "at-risk" due to mental illness, doesn't mean he wasn't targeted and persecuted. Instead, his depression was swept under the rug by the filmmaker, as it so often is in our society.

Overall, this is a very important film and I would highly recommend it. However, read Aaron's blogs and writings for supplemental info!

9xWRL

The tragic story of Aaron Swartz, told by those closest to him

This warm yet chilling documentary retraces the life of Aaron Swartz, who committed suicide at age 26 after a couple of years of severe and deepening pressure from the criminal justice system, which was trying him for a number of felonies resulting from his breaking into MIT's computers.

We first see him as a young kid in home movies, then as a prodigy who while very young was brimming with new ideas for the Internet and applied genius-level programming skills to co-developing RSS and Reddit. Bored with college and with working for the business establishment, he turned to activism, promoting an open Web culture for the benefit of all users.

Swartz's activism turned into hacktivism, landing him in deep trouble with the Justice Department, which charged him with crimes that could have sent him to prison for 35 years. Touching, pointed accounts from family members and close associates describe what Aaron was like and how he responded to unyielding Justice Department efforts to use him as an example.

The interviews with law professor Lawrence Lessig and World Wide Web inventor Tim Berners-Lee are unforgettably moving. The film does a good job of calling into question Swartz's harsh treatment by the same Justice Department that shied away from prosecuting the big money interests that brought down our financial system.

Whether you sympathize with Swartz or not, the film does a solid job of showing how blind justice in the U.S. can be when it wants to be.

We first see him as a young kid in home movies, then as a prodigy who while very young was brimming with new ideas for the Internet and applied genius-level programming skills to co-developing RSS and Reddit. Bored with college and with working for the business establishment, he turned to activism, promoting an open Web culture for the benefit of all users.

Swartz's activism turned into hacktivism, landing him in deep trouble with the Justice Department, which charged him with crimes that could have sent him to prison for 35 years. Touching, pointed accounts from family members and close associates describe what Aaron was like and how he responded to unyielding Justice Department efforts to use him as an example.

The interviews with law professor Lawrence Lessig and World Wide Web inventor Tim Berners-Lee are unforgettably moving. The film does a good job of calling into question Swartz's harsh treatment by the same Justice Department that shied away from prosecuting the big money interests that brought down our financial system.

Whether you sympathize with Swartz or not, the film does a solid job of showing how blind justice in the U.S. can be when it wants to be.

Morality-Tale for Our Times

The story of Aaron Swartz, who killed himself at the age of 26, is sad but inevitable consequence of the world we inhabit.

From his earliest days, he was a prodigy, not only developing the skills of reading and processing information at an early age, but acquiring a unique ability to write programs and offer innovative solutions to many problems presented in the early years of the Internet. With the help of testimonies from Swartz's family, plus colleagues and friends including the inventor of the web, Tim Berners-Lee, Brian Knappenberger's film traces the meteoric career of a genius who appeared to be able to offer solutions that no one else could. More significantly, Swartz had the ability to communicate with his interlocutors, not just in small-group situations but in public arenas as well. This is what rendered him such a powerful figure; although physically diminutive, he had a gift for speech-making that proved hypnotic in its effect.

Matters came to a head, however, when Swartz hacked the JSTOR sits, an address used mostly for publishing scholarly journals across all disciplines, downloaded the information and made it available to all web users. This completely contravened JSTOR's principle, which was to make that information only available to subscribers, mostly in academic institutions. The principle might have been a noble one (why shouldn't all users have equal access to information, especially if it aids their research?), but the American government's response was predictably harsh, as they charged Swartz with a variety of crimes under an Act issued as long ago as the mid- Eighties.

Knappenberger's film suggests with some justification that this reaction was ludicrously out of proportion to the nature of Swartz's so-called 'crimes.' He had neither challenged the Constitution nor caused harm to others; on the contrary he had simply worked in the interests of democratization. He was the victim of the same kind of paranoia that underpinned the anti-communist campaigns six decades ago, when legions of innocent people were rounded up and made to 'confess' their alleged involvement with a plot to subvert the American way of life, even if they had not done anything. The same applied to Swartz, who was offered the promise of lenient legal treatment in exchange for a 'confession.'

The familiarity of Swartz's plight suggests that a climate of intolerance still exists in a country that consistently advertises its democratic credentials, especially when compared with other territories in the world. THE INTERNET'S OWN BOY suggests otherwise; if the government was truly democratic, it would either have understood Swartz's motives, or meted out the same harsh treatment to other criminals - such as those who precipitated the Wall Street crisis of 2008. But who said anything was truly equal in American society?

THE INTERNET'S OWN BOT is a polemical piece that leaves viewers feeling both angry and frustrated - angry that a talented soul like Swartz should have had his life cut brutally short, and frustrated that the government should have pursued such heavy-handed treatment. If the film can inspire more activism to try and change official policies, it will have achieved much.

From his earliest days, he was a prodigy, not only developing the skills of reading and processing information at an early age, but acquiring a unique ability to write programs and offer innovative solutions to many problems presented in the early years of the Internet. With the help of testimonies from Swartz's family, plus colleagues and friends including the inventor of the web, Tim Berners-Lee, Brian Knappenberger's film traces the meteoric career of a genius who appeared to be able to offer solutions that no one else could. More significantly, Swartz had the ability to communicate with his interlocutors, not just in small-group situations but in public arenas as well. This is what rendered him such a powerful figure; although physically diminutive, he had a gift for speech-making that proved hypnotic in its effect.

Matters came to a head, however, when Swartz hacked the JSTOR sits, an address used mostly for publishing scholarly journals across all disciplines, downloaded the information and made it available to all web users. This completely contravened JSTOR's principle, which was to make that information only available to subscribers, mostly in academic institutions. The principle might have been a noble one (why shouldn't all users have equal access to information, especially if it aids their research?), but the American government's response was predictably harsh, as they charged Swartz with a variety of crimes under an Act issued as long ago as the mid- Eighties.

Knappenberger's film suggests with some justification that this reaction was ludicrously out of proportion to the nature of Swartz's so-called 'crimes.' He had neither challenged the Constitution nor caused harm to others; on the contrary he had simply worked in the interests of democratization. He was the victim of the same kind of paranoia that underpinned the anti-communist campaigns six decades ago, when legions of innocent people were rounded up and made to 'confess' their alleged involvement with a plot to subvert the American way of life, even if they had not done anything. The same applied to Swartz, who was offered the promise of lenient legal treatment in exchange for a 'confession.'

The familiarity of Swartz's plight suggests that a climate of intolerance still exists in a country that consistently advertises its democratic credentials, especially when compared with other territories in the world. THE INTERNET'S OWN BOY suggests otherwise; if the government was truly democratic, it would either have understood Swartz's motives, or meted out the same harsh treatment to other criminals - such as those who precipitated the Wall Street crisis of 2008. But who said anything was truly equal in American society?

THE INTERNET'S OWN BOT is a polemical piece that leaves viewers feeling both angry and frustrated - angry that a talented soul like Swartz should have had his life cut brutally short, and frustrated that the government should have pursued such heavy-handed treatment. If the film can inspire more activism to try and change official policies, it will have achieved much.

Did you know

- Quotes

First Title Cards: Unjust Laws exist; shall we be content to obey them, or shall we edeavor to amend them, and obey them until we have suceeded, or shall we transgress them at once?- Henry David Thoreau

- ConnectionsFeatures The Wizard of Oz (1939)

- SoundtracksExtraordinary Machine

Written and Performed by Fiona Apple

- How long is The Internet's Own Boy: The Story of Aaron Swartz?Powered by Alexa

Details

- Release date

- Country of origin

- Official site

- Language

- Also known as

- Internets underbarn

- Production companies

- See more company credits at IMDbPro

Box office

- Gross US & Canada

- $48,911

- Opening weekend US & Canada

- $21,705

- Jun 29, 2014

- Gross worldwide

- $48,911

- Runtime

- 1h 45m(105 min)

- Color

- Aspect ratio

- 1.78 : 1

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content