Unable to find the war he has been asked to cover, a frustrated war correspondent takes the risky path of co-opting the identity of a dead arms-deal acquaintance.Unable to find the war he has been asked to cover, a frustrated war correspondent takes the risky path of co-opting the identity of a dead arms-deal acquaintance.Unable to find the war he has been asked to cover, a frustrated war correspondent takes the risky path of co-opting the identity of a dead arms-deal acquaintance.

- Awards

- 5 wins & 2 nominations total

- Robertson

- (as Chuck Mulvehill)

- Hotel Clerk

- (uncredited)

- Murderer's accomplice

- (uncredited)

- Cameraman

- (uncredited)

Featured reviews

"The Passenger will remain a film of the mid '70s, as one of Antonioni's previous films, Blow-Up, remains a film for and symbolises the '60s. It also contains one of Jack Nicholson's definitive performances (along with Chinatown, The Last Detail and One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest) and has, perhaps, been a trifle overshadowed by these films all emerging within a short period of time of each other and the enormous publicity and word-of-mouth they have generated. But The Passenger has proved itself a strangely durable film and, like Chinatown, one that will remain around for a long time, both in the consciousness of its admirers and, one hopes, constant revivals.

Antonioni's third English-speaking film, The Passenger, like Blow-Up and Zabriskie Point, centres around the oblique, unresolved aspects of life. In Antonioni's films - as in life - there are no easy answers, things are not tidied up, explained, sorted out.

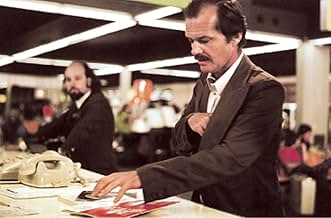

So it is with The Passenger. Jack Nicholson is Locke, an outwardly successful television journalist, but he also is being eaten away by his own disillusionment with the job and the value of his interviews, and that general malaise that affects Antonioni's people. When the film begins, we find him on location in Chad where his jeep breaks down and gets bogged in the sand. Locke breaks down and collapses on the sand as the camera pans away over the strange but beautiful desert panorama.

We next see Locke, in an advanced state of exhaustion, struggling back to his hotel and a cool shower, and discovering that the man in the next room, who looks rather like him, has died. We are very conscious of the stillness in the hotel - the blue walls, a fly buzzing, the noise of the fan, Locke staring intently at the dead man on the bed. We hear their dialogue of the previous evening and the aural flashback changes to a visual one by some very neat editing. Locke changes rooms, passport photos and luggage, and finds it quite easy to take on a new identity. How desperate his need is can be judged by his conversations back in Europe with the free, liberated girl (Maria Schneider) he meets up with. ("I used to be somebody else, but I traded him in"). She, incidentally, is freer than Locke could ever be.

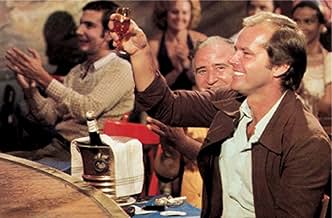

It transpires Locke has taken over the identity of a gun-runner, Robertson. Perhaps it is best not to go into the plot in too much detail. Best all round just to pick out some of the marvellous moments along the way to the final breathtaking conceit. There's Locke, back in London, daringly visiting his old haunts - delighting in being someone else, but of course he isn't. Later on he is suspended in a cable car high about the ocean his arms outstretched like a bird in flight. Later still, the girl asks him what he is running from, and he tells her to turn around and we see what she sees - the road behind them.

By now, we the audience are caught up in this mesmerising film and its deliberations of he mysteries of identity. We are now totally involved in Locke's plight. He has given up one identity for another and becomes more and more helpless as the situation gets out of his control. Finally, in a remote Spanish hotel he can go no further, either as himself or as his new identity, as his wife and the gun-runners close in on him. One shouldn't spoil the last sequence for those still to see it, but it shows the only real freedom from identity and self is in death. The final scene shows us the aftermath: as the sun goes down, the hotel-keeper comes out for a walk, a woman sits in the doorway resting. For some people, who do not question their existence, the continuity of life goes on.

Antonioni, now in his sixties, is one of the great Italian directors who, like Fellini and Visconti, burst upon the international film scene in the late '50s. His trilogy of Italian films, L'Avventura, La Notte and L'Eclisse, and his first colour film The Red Desert (all with Monica Vitti) contributed to the renaissance of the European cinema. Then he switched to his English-speaking films, of which Blow-Up was the first. He is as much a master of landscape as John Ford was in his genre. He thinks nothing of painting whole streets or trees to get the effect he wants. Blow-Up is the only film from the whole, crazy period of Swinging London films that has not dated and which encapsulates what it was really all about. It remains one of the great films. Like Bergman, Bunuel or Fellini you either respond to his vision or reject it totally. His images linger on in the mind, his work never dates."

That is what part of what I wrote in 1976 and The Passenger indeed remains endlessly fascinating and particularly so now that it is available again. Even at the Antonioni retrospective in 2005 it was not available to include in the season, but we did have cast members Jenny Runacre and Steve Berkoff there to speak warmly of it's making and importance.

Let's hope a new generation will discover its timeless appeal, and amazingly Antonioni now in his 90s is still with us, if rather frail. A 2005 short of his was shown last year on the great statue of Moses in Rome and was also in its own way fascinatingly mysterious.

Some may find the opening twenty minutes of the film, where there is virtually no dialogue, hard-going but this perfectly illustrates the sparse and confusing environment of the North African desert where the film begins. We are also treated to a marvellous scene between Locke and the man whose identity he later assumes where a tape recording and flashback are ingeniously merged into one and then separated again. Antonioni creates a mood that is almost indefinable throughout, a kind of hollow detachment which is exactly the perspective that Locke has on the world which has gradually worn him down yet the director still manages to conjure up power and simple romance between Locke and the girl he meets who is played by Maria Schneider. The film was not a hit at the box-office which is not surprising considering it's uncommercial style but artistically and cinematically it is a triumph of innovation.

Thirty years later, Michelangelo Antonioni's re-released "The Passenger" is looking very good, and so are Jack Nicholson and Maria Schneider, as the journalist who takes a dead man's identity in the Sahara and the girl he meets in Barcelona who decides to tag along. David Locke (Nicholson) takes the passport of a man named Robertson who he's had a few drinks with in a hotel. Before that we see Locke experience frustration, giving away cigarettes to men in turbans who say nothing, abandoned by a boy guide, dumping a Land Rover stuck in the sand. Later we see films that show as a journalist he was subservient to bad men. Locke has Robertson's appointment book which leads him to Munich, then various points in Spain. He learns Robertson was a committed man taking risks: he sold arms to revolutionaries whose causes he thought were just. He gets a huge down-payment.

Then Locke's wife gets a tape of him talking to Robertson and his passport with Robertson's photo pasted into it -- and she gets the picture.

Changing your identity and using someone else's isn't just an existential act, it's also a criminal one. Locke's gambit is hopeless: he winds up fleeing from himself. The film skillfully gives its action story an existential underpinning. The chase keeps up a rapid pace, like the Bourne franchise, but it has time to contemplate Locke's old and new lives in a metaphorical story he tells Schneider about a blind man that explains how he ends up.

Antonioni is great at little incidentals -- a girl chewing bubblegum, a man reciting in a Gaudi building. And at the end, people coming and going in a desolate plaza outside a bullfighting amphitheater. The locations provide exotic glamor. The camera-work of course is wonderful. In retrospect now one can see this was definitely a culmination for Antonioni. He thought it technically his best film. This is the director's preferred European version, originally released as "Professione: Reporter."

Despite its power and polemic against journalism, Professione: Reporter is also an understated movie from start to finish, made for a grown-up audience. Nothing is spelt out for you. However, the movie is strewn throughout with powerful and evocative visual clues, so it's nonetheless up to you as an attentive viewer to pick up (the early scene of Locke's Jeep getting stuck in the African desert sand, anyone?), or even soak them up unconsciously. As with all Antonioni, every shot in this movie is worthy of analysis and admiration. Bergman once said about the Italian that he could create some arresting individual images, but was incapable of stringing them all together in the sequence of a palatable movie: sorry Ingmar, old man - as much as I feel in awe of your craft, you're talking nonsense, here. However, I can't believe Antonioni once had the cheek to say he improvises each scene as he goes along (see his IMDb quotes page). There isn't a chance in hell these meticulously crafted, immaculately framed and composed movies are not also carefully premeditated. Clearly, Antonioni was trying to start a myth about himself along the lines of the one about Mozart composing his music straight onto the page, as dictated by God. In Professione: Reporter, I was especially in awe of the sequence involving the single long take from the window of Locke's last hotel room in an unnamed, dusty Spanish village. Regarding Maria Schneider, it truly is a shame she wasn't the star in a greater number of successful movies. Her ambiguity makes it very difficult to keep one's eyes off her when she's on screen. She looks like a cross between a boy, a girl and something cutely ape-like (I mean it in a good way!).

I would like to warn viewers of the inclusion of footage of a real execution - again, this was a film within the film. Personally, I found it very disturbing, which is why I'm mentioning it here.

The camera is always our eye, taking in sweeping panoramas of the North African desert to an architectural tour of European churches and an appreciation of the variegated urban and rural landscapes of Moorish Spain, still showing relics of older invasions, where it all comes together as we literally go from dust to dust. We are the passengers on this existential trip to try and change identities through someone else's travels logging almost as many locations as an outlandish Bond film .

Because so much of the film is dispassionately observational about natural landscape and cityscape, and windswept plazas that provide imitations of nature within a city, it stands up through time, even as the 1975 clothes, hair, TV journalist technology, and, somewhat, male/female relationships, look a bit dated and we can no longer assume that African guerrilla fighters and gun dealers helping them are more noble than the corrupt inheritors of colonialism.

The camera is constantly picking out culture contrasts - camels vs. jeeps, horse-drawn carriages blocking Munich traffic, Gaudi's serpentine architecture vs. Barcelona's modern skyline, a cable car gliding over a shimmering body of water.

And, of course, the very American Jack Nicholson in a very European film, with the many layers of meaning as he plays an adventurous broadcast reporter who ironically tries to escape the truth about himself. His young, sexy, challenging self is surprisingly effective here as we believe both his ethical lapses and his obsession.

Avoiding the narration that a film today would utilize, Antonioni well takes advantage of what now looks fairly primitive tapings of the reporter's past and current interviews to convey background and flashbacks on characters through minimal explication with overlapping sound and gliding visuals. The intertwined story lines constantly re-emphasize the point of not really knowing a person or a culture from the outside, with a repeated refrain of "What do you see?".

Maria Schneider's character skirts just this side of a male fantasy cliché, though Antonioni helped to create the type, and a few subtle plot points save her from total disingenuous sex kitten femme fatale (even as her character shrugs that one plot point is "unlikely"). Nicholson's repeated refrain to her of "What the f* are you doing with me?" takes on different meanings as we know more.

I'm not sure if this 2005 re-release of the director's cut, with supposedly nine minutes that were not in the original U.S. release, is notably pristine, as it wasn't particularly sharp, but the director's trademark crystalline blue sky is still breathtaking and is a must-see in a full screen rather than on DVD. The views practically feel like the old Cinemascope.

A climactic landscape shot brings all the violent, sensual, philosophical and narrative plot and thematic points together in a marvelous way that has been much imitated but is still powerful, as the camera looks out a window at a cool distance in the heat, key events culminate back and forth frantically in front of the camera, in and out of frame, and the camera moves through the bars and is free to roam in ever more close-ups.

Did you know

- TriviaWhen Michelangelo Antonioni received his honorary Oscar in 1995, the Academy asked Jack Nicholson to present it to him.

- GoofsThere are a couple of inaccuracies in the displayed details of Locke's Air Afrique air ticket that was evidently issued in Douala, Cameroon in August 1974. The name of Fort-Lamy (Chad's neighboring capital city) became N'djamena in early 1973, and Paris is written in Italian ("Parigi") which would not have occurred in French-speaking Douala.

- Quotes

The Girl: Isn't it funny how things happen? All the shapes we make. Wouldn't it be terrible to be blind?

David Locke: I know a man who was blind. When he was nearly 40 years old, he had an operation and regained his sight.

The Girl: How was it like?

David Locke: At first he was elated... really high. Faces... colors... landscapes. But then everything began to change. The world was much poorer than he imagined. No one had ever told him how much dirt there was. How much ugliness. He noticed ugliness everywhere. When he was blind... he used to cross the street alone with a stick. After he regained his sight... he became afraid. He began to live in darkness. He never left his room. After three years he killed himself.

- Crazy creditsLeo, the MGM lion, which normally precedes the opening credits of MGM movies, has been supplanted by "BEGINNING OUR NEXT 50 YEARS". Leo then returns in the center with "GOLDEN ANNIVERSARY" on either side of it.

- Alternate versionsSeven minutes were added to the 2005-2006 re-release version, including a brief shot of a nude Maria Schneider in bed with Jack Nicholson in the Spanish hotel.

- ConnectionsFeatured in Z Channel: A Magnificent Obsession (2004)

- How long is The Passenger?Powered by Alexa

Details

- Release date

- Countries of origin

- Official site

- Languages

- Also known as

- Zanimanje: reporter

- Filming locations

- Fort Polignac, Algeria(desert scenes, setting: Chad)

- Production companies

- See more company credits at IMDbPro

Box office

- Gross US & Canada

- $620,155

- Opening weekend US & Canada

- $24,157

- Oct 30, 2005

- Gross worldwide

- $818,936